Societal biases affect women in science

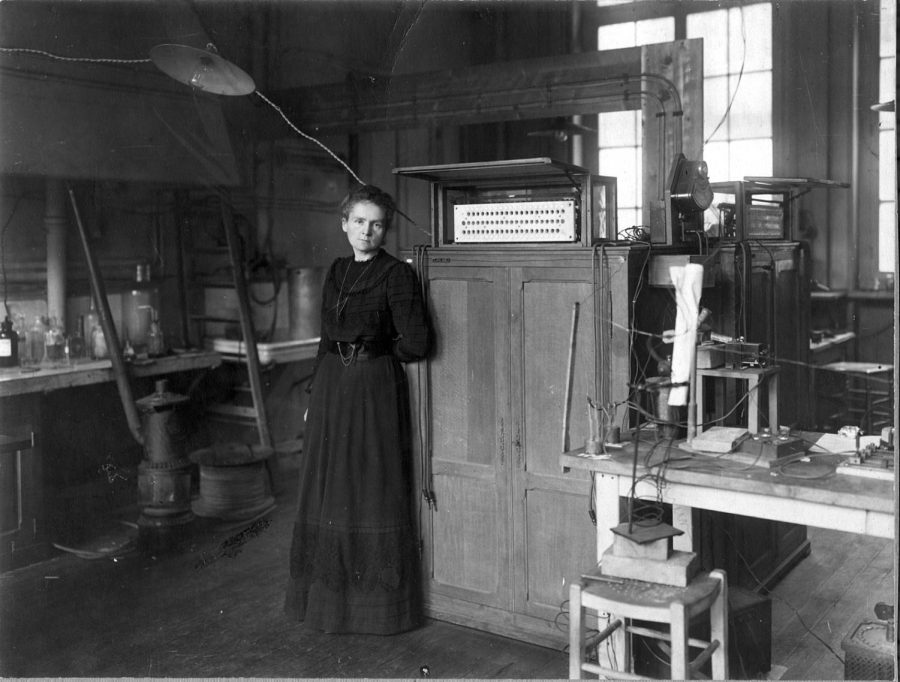

Wikimedia Commons

Marie Curie in her Paris laboratory (1912). Marie Curie was the first female to win the Nobel Prize in Physics and Chemistry.

January 25, 2023

In 1911, Marie Curie, a female physicist, won a Nobel Prize for her discovery of radium. As the first female to win a Nobel Prize, this is undoubtedly one of the most notable moments in the history of science. However, Marie Curie’s discovery did not instantly change the perception of many people toward women in science.

The number of women in the field of science has significantly increased over the years. “Women made gains – from 8% of STEM workers in 1970 to 27% in 2019,” according to the Census Bureau. However, one problem remains: gender equality in the field of science remains far from being realized.

While the experience of each female scientist may differ, rarely have any experienced equal treatment to men in their careers. ‘Almost Famous,’ a series of short films directed by Ben Proudfoot and published by the New York Times, features people that have “nearly made history – and were happy anyway.” In the episode “I Changed Astronomy Forever. He Won the Noble Prize for It” female astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell Burell talks about gender inequality in her education. She says, “They sent the boys to the science laboratory and the girls to the cookery room because they were going to be homemakers. I knew that wasn’t right.” This unfortunate reality check was one of many more to come for Professor Burell, who pursued her passion for science, especially astronomy. She attended the University of Glasgow in Scotland as the only female in a class of 50, where “when a woman entered the lecture theater, all the guys whistled, cat-called, (and) banged their desks.” She goes on to say that if it weren’t for her passion for astronomy, she would have opted for another field. Advancing further in her career, she attended the University of Cambridge where she assisted the astronomer Anthony Hewish. Her attention to results that differed from their hypothesis led to the discovery of pulsars. Although the experiment was a collaborative effort made by both Hewish and Professor Burell, only Hewish was credited for this groundbreaking discovery, as he alone was later on awarded the Nobel Prize. Professor Burell says, “Tony could have cited me more and didn’t, but I was Miss Bell, the student.” Even when she did receive attention from the press, the press asked questions that were completely unrelated to her contribution to the discovery of pulsars. “The popular press were certainly putting me in the little girl, sexually attractive role. I barely rated as a scientist. Tony just let it happen. It was dreadful.”

Compared to when Professor Burrell was a student, today’s society has dramatically moved forward for women in the field of science. The number of female Nobel Prize winners is now 61, and nearly 30% of the world’s scientific researchers are women, according to UIS data. However, it is still far from 50% and more work needs to be done, starting in schools.

Ms. Mendoza, a Science teacher here at ISSH, recalls that in the previous co-ed school that she taught in, girls would back away from taking part in experiments, letting the male students take the lead. Similarly, Ms. Peck noticed that at her previous co-ed school that when a male co-worker taught her class “only boys would raise their hands.” However, when she taught the class, both girls and boys would raise their hands to answer questions. Ms. Peck also says that “who your teacher is and what female influences you are surrounded by can help students feel more comfortable if they (the students) are female as well.”

Ms. Humphrey, one of the science teachers also says “the real issue is getting female scientists into fields of study that are lacking female representation.” For example, in fields such as engineering, there is a skewed ratio of females to males. According to Pew Research Center, “engineering occupations have the lowest share of women at 14%.” To prove this, Ms. Janssen, High School STEM teacher at Hiroo Gakuen, spoke about her personal experiences studying biochemical engineering. “When you walk into a room and you don’t see yourself represented, it’s really hard to feel like you belong in that environment. Oftentimes, I was the only woman in the class. I was in classes with 40-50 men and very few women.” She also describes her degree, biochemical engineering, as a very “rigorous” course. “By my third year, others started to fall behind. That’s when they start to get nervous and start elsewhere. Most of my companions dropped out [of the course] by my third year.” On top of this, she also said that she had to endure mansplaining from her fellow male classmates, who tried explaining concepts or ideas to her even though she had studied that particular subject.

When asked about the hope for the future generation of female scientists, Mrs. Mendoza responded by saying that “one day, whether you are male and female, if they want to do something, I hope that they won’t have a thought, because I’m a female, I can’t.” She goes on to say, “I think it’s both intrusive and extrusive because as a student, you don’t think it until you see it, right? If you see that there are a lot of doctors that are male, would you push yourself to become a doctor if you know you can’t compete in such a field?” Therefore, seeing an underrepresentation of women in the field of science can discourage female scientists, which could cause them to second guess or withdraw from pursuing their true passion.

Finally, not only should female scientists stand up for the injustice that women receive in science, but male scientists should speak up for women as well. When asked if she witnessed sexist behavior within work settings, Ms. Janssen said, “There was one occasion when the teacher who was the head of the department, said something so outrageously sexist that I was just flabbergasted. I was like saying, you cannot have possibly just said that. My other (male) co-workers looked at me and afterward agreed that what the teacher said was sexist. But by not saying anything, you are just continuing sexist behavior by letting it happen. Why is the burden always on the minority to say something?”

All in all, there is still much work that needs to be done for a world where female scientists are fully included in the scientific community. Having strong female figures around them often encourages female students to reach their full potential. Therefore, having more representation of women in science is essential for future generations of female scientists who want to pursue an educational career in science. In addition, just because females are the ones suffering from gender inequality in the field of science, that does not mean that men cannot speak up or address the issue as well.