When speaking to Michael Finkel, Stephane Breitwieser claimed that art museums were “prison for art.”

Breitwieser thinks of museums as cages, places from which art should be liberated. He thinks art is beautiful, and art shouldn’t be stuck in a cage. In museums, you can’t sit comfortably, lounge as you absorb the piece next to you; you can’t be at peace, burdened with the weight of being in public; you can’t touch the art, restrained by rope barriers and glass cases.

He thinks this is all wrong. He thinks art is beautiful, and beautiful things shouldn’t be caged: not by abstract, social, or physical barriers. In museums, we are denied the opportunity to truly appreciate art, wholly immerse ourselves in beauty – isn’t that wrong?

Breitwieser calls himself an art lover. The rest of the world calls him a thief who stole $2 billion worth of art. (You can read more about Breitwieser’s baffling escapades in Finkel’s New York Times best-seller non-fiction biography about Breitwieser, The Art Thief.)

Usually, it is frowned upon to give credence to the ramblings of a prolific criminal, especially one who, ironically, was jailed because of his obsession with this aforementioned beauty. But he isn’t the only one who feels bitterly about museums.

In 1793, the Louvre was opened to the public by the radical revolutionary government. It had originally been an expansive royal art collection accumulated over centuries: but the common people wanted a look at all the beautiful artwork, too.

For years, secular art in the way we think of it now had been an affair meant for the wealthier. Affluent families could commission the most talented of artists to paint for them on the most trendy of materials: such was the case with the de Medicis of Florence.

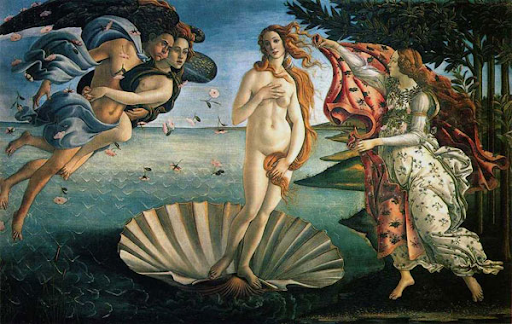

Incredibly wealthy and in possession of a countryside home that needed an artistic touch, the family commissioned a young artist to paint a canvas painting: after two years of work, the artist, Botticelli, finished the painting, The Birth of Venus. The painting remained at that same cottage for over 300 years, for the family and the family only to view. This trend continued with the advent of salons and private collections during the Enlightenment, where members of the upper echelons would gather to discuss all things Enlightenment. Sometimes, artists were guests, welcome to gush about their masterpieces to adoring audiences. Here, attendees learned to study art, to interpret art, to love art. And they had all the resources they needed to learn to adore it – a cushy atmosphere, correspondence with the sources of the pieces themselves, and all the time in the world. For these individuals, viewing art wasn’t a casual hobby – art was wonderful, and it was all-encompassing.

And it just so happened that a collection of these wonderful pieces resided right in Paris – so Enlightenment thinkers like Encyclopedia author Denis Diderot began advocating for national art museums so that these pieces could be shared with the public. When the Louvre first opened, it was open for 6 out of 10 days of the revolutionary calendar week, and has remained open almost consistently since.

Art museums quickly became more and more popular – many pieces from private collections of wealthy families became available for the public to see. Venus herself moved from the Medici’s lavish summer cottage to a public museum in 1815. The Uffizi, its new home, had opened its doors for all almost 50 years earlier, as another museum filled with donated artworks.

As Europe and America industrialized and the proletariat had the time and money for leisure, museums became increasingly more popular. Visiting them was considered to be a refined activity and perhaps a bit more righteous of leisure. The museum “counteracts the influence of a saloon and of the race-track,” claimed museum curator and anthropologist Franz Boas.

But now, museums are not as revered. There have been several opinion pieces both from online forums and reputable websites detailing how miserable the museum experience is – CNN’s 2013 opinion piece “Why I hate museums,” Sydney Morning Herald’s 2014 Traveller article “Boring, pricey and crowded: 17 reasons why I hate museums,” and 2016 “Why I hate museums and cannot be bothered by the Mona Lisa” amongst them. Although it might be easy to scoff at the admittedly snarky titles, these non-criminals do seem to corroborate Breitwieser’s distaste for the museum.

In the aforementioned CNN opinion piece, James Durston says that he leaves museums “bored [and] hungry.” He hates that all there is to do is look at the exhibitions and read the little professionally-toned placards. The strict expectation to be a silent (or as he calls it, “censured”) museum guest peeves him. Michael Koizol’s Sydney Morning Herald article puts this more simply: “I guess what I really require [to enjoy museums] is action. Lights, sound, movement. Pizzazz.”

In the Traveller article, writer Oliver Smith says that it’s hard for him, a layman, to distinguish between all these artworks – nothing differentiates one artist from another – and the atmosphere makes the experience much worse. “Hospital-like,” Smith calls it, and filled with people who will angrily stare you down if you make noise, force you to move along the line so they can take pictures with the artwork, and whose unknown voices echo through the halls.

This proposes the real question: what should we do about the miserable art experience? According to Breitwieser, Durston, Koizol and Smith, something has to change if we want the art museum experience to be more enjoyable.

In exchange for making art more available to the common person, the art viewing experience has seemingly gotten worse. If art is an engaging experience, where we have access to the artists and can wine and dine with our friends, relaxing and laughing in a private salon while reviewing each piece, art will only be accessible to the upper echelons: those with lots of time and lots of money.

However, if we make art accessible and put these masterpieces into public buildings, we must accept that the experience will be tainted by the pitfalls that come with being in public, amongst others – like we have when we share with others, there will be time restrictions on how long we can hog a painting; like any other time we are in an area where others need to focus, to contemplate, we must be quiet, and we must be able to tolerate the echoes of other moving around us. Hell is other people, after all, but it’s difficult to complain when we create this public space for hell, and we willingly visit it.

Your experience with art will always be inhibited when you’re viewing art in a public museum, because the exhibition can’t cater to just your needs. Experiencing art will always be pay to view, whether it’s the cost of the $5 entry ticket or the cost of curating the experience to your needs. But while most of us cannot afford to shell out thousands, if not millions, for a personal cabinet of curiosities, we can spare $5.

Art museums aren’t the most perfect way to experience art, but they’re doing their best to preserve history, conserve culture, support artists, and foster a sense of appreciation and even affection for art – and if we have to give up snacking and commentating for an hour or so, so be it. Arguably, when put next to the alternative of art being a privilege only for the mega-rich, public art museums are the lesser of two evils.

But art museums are kind of in a tough spot. We often think of art museums as beloved institutions – although this might be true in theory, we don’t quite see this manifesting. A study conducted by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences reports that only 24% of the surveyed population reported attending an art gallery or museum in 2017, and research published by the Art Fund in 2024 states that two-thirds of museum directors say they are concerned about a lack of funding. The same study reports that these museum directors estimate that it would take 10 to 20% more funding “just to stabilize.”

Whilst it is unlikely that the Louvre will shut down anytime soon, this instability can be brutal for smaller museums. It’s important to support these institutions that allow us to have access to art, where most of us would never have had these opportunities two and a half centuries ago.

You don’t have to be a super-wealthy donor to lend museums a helping hand. If you have a day off, take a trip to your local museum with your family and friends. If you don’t want to elbow your way through a crowd just to look at a vase, check Google’s “Popular Times” function and plan your trip accordingly.

If you can’t go to the museum, send your child to the museum’s summer art camp or do a one-night painting class. If it’s not feasible to go to another country to visit a museum, apps like Smartify let you buy souvenirs that support these museums right from your couch. If you have time, volunteer or sign up to become a docent. Even just writing a good review or interacting with the museum’s social media can help.

And these efforts wouldn’t be for nothing – they can’t do everything to please the entire public, but art museums are making changes to try and adapt to this new generation. From museums like the Yayoi Kusama Museum in Tokyo introducing timed tickets which prevent overcrowding, the Kunstmuseum in the Hague’s Chamber of Wonders, where visitors can interact with the museum’s artworks through projections, and the Art Institute of Chicago hosting talks with artists whose pieces they carry, there is an effort to make the atmospheres of museums better. These solutions address the concerns of Durston, Koizol, and Smith: they make the museum less stuffy; they add more “lights, sounds, movement […] pizzazz;” they help the audience see what makes each artist special through talks with the artists themselves.

But if a museum doesn’t have support, it can’t exactly put these measures into effect.

So yes, keep publishing your articles and comments on what changes you’d like to see in art museums – but also make sure that art museums are funded enough to continue letting the arts be accessible to us, and to be able to change what they can as a public space. After all, beautiful things shouldn’t be caged, certainly not by budget cuts, financial struggles, or low museum attendance.