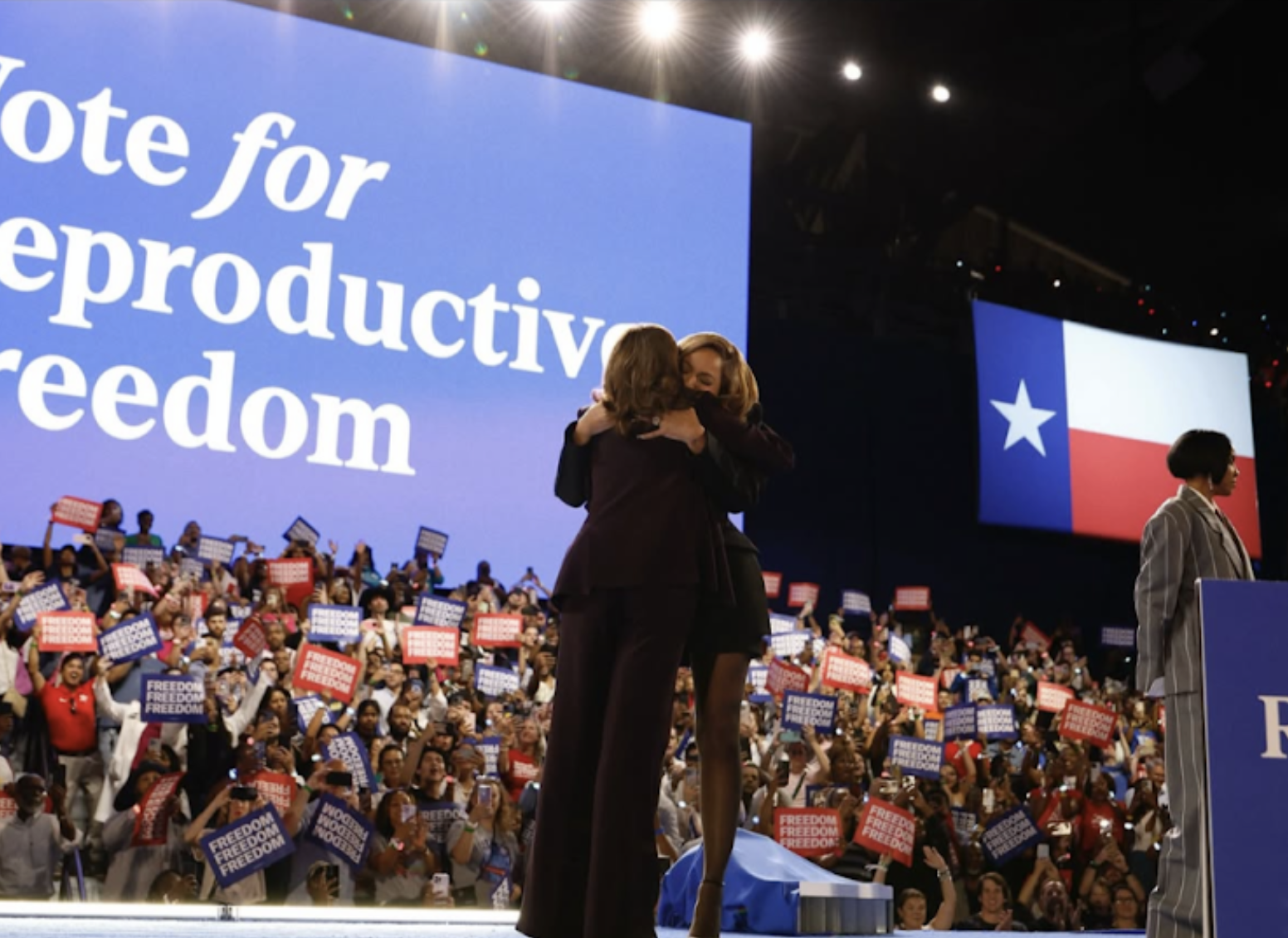

At the end of last year, at the Kamala Harris Rally in Texas, Beyoncé spoke to encourage people to vote and use their voices to bring a better future for America, especially for women. Her speech centered around her hopes that women can imagine a future without limits. She emphasized that she is “here as a mother” while simultaneously failing to mention and speak up about the war in Gaza—which has killed 8,304 women and 15,613 children—that the Biden-Harris administration had been funding. She and many others fail to acknowledge that, beyond their borders, the bombing of a foreign nation is a threat to feminism.

This is a prime example of how Western feminism often neglects what’s happening abroad if it doesn’t fit their narrative of “a future without limits” or if it’s too complicated. Feminism is supposed to fight for equality, justice, and freedom for all women, but that’s not necessarily the case. While feminism is often portrayed as a universal movement, feminism in the West often neglects the unique struggles of women in non-Western and conflict-ridden contexts. It fails to address the lived realities of women beyond its borders.

This is because Western feminists have the privilege to look away. When the problem is too complicated or too much to handle, they have the ability to turn their screens off or talk about something easier, and simplify issues to dress codes or whether women who don’t live in the West are allowed to go to school. While these issues do need to be talked about, often the issues get drastically simplified to the point where we can’t even recognize the root of the problem at hand, or they speak about issues that aren’t prioritized by the women they’re speaking for.

Many Western feminists choose to simplify issues or ignore them rather than attempt to solve them or speak out. The privilege to look away and the simplification of issues skews the priorities of what should be discussed when talking about the struggles of women, especially those who don’t live in the West. This becomes evident when we see media outlets and public figures are selective about which issues to report and which ones to ignore.

The reactions to hijab mandates versus hijab bans are the most evident of these examples.

In Iran, the hijab is compulsory for women, and this law has been met with outrage from the West. Media outlets wrote many stories, calling this law oppressive to women and demanding a change. Meanwhile, in France, the wearing of religious symbols in public places, including public schools, is banned. The ban includes the hijab and the abaya (a traditional loose dress often worn by Muslim women). By imposing this ban, the Western media has completely ignored Article 18 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights—the human right of freedom of religion, which seems to only apply to non-Western countries. Alongside Afghanistan and Iran, France is the only other country to legislate what women can and cannot wear, yet we only hear protests about Iran and Afghanistan.

Many media outlets have neglected to talk about the bans, keeping the struggle of Muslim women in the West unnoticed. The reaction to hijab mandates is hypocritical when compared to the complete silence regarding the hijab bans. The same women who fight for women in Afghanistan and Iran don’t question France’s policy of banning religious symbols from public areas, highlighting the double standard present in feminism that is viewed through a Western lens. This silence speaks volumes: if the issue doesn’t align with Western feminist priorities, it simply doesn’t matter.

This skewed perception can also be found when talking about the women in Syria. Women in Syria have been suffering for over 14 years under a dictatorial regime. Many women were imprisoned, tortured, raped, and then, if impregnated, forced to carry the pregnancy to term, give birth, and raise the child in the prisons. Yet the media has rarely covered this, and the women who advocate for women’s rights have failed to address the struggles of the women of Syria. It’s as though if you can’t see the suffering of women, it doesn’t exist.

Syria has transitioned under new leadership in the past few months, with Ahmed Al-Sharaa as the transitional President. In an interview by BBC with Ahmed Al-Sharaa, one of the questions asked whether women would be able to attend school. While this is a valid concern, why was this was the first time women’s rights were mentioned right after a country had just gained its liberation, and not when women were getting killed and raped? If the West truly cared about the women of Syria, they would not have let the Assad regime last as long as it did. The global concern for women’s struggle in Syria seemed to appear only when it could be framed within a narrative of Islamic oppression of women. The media and other political feminists act as if the suffering of Syrian women had only begun with the rise of an Islamic leader, highlighting where the prejudices of these feminists lie.

Photo: Abdel Hassouni, (CC-4)

Western feminists frequently frame Muslim women’s access to education as an issue of oppression, assuming that Muslim-majority societies inherently suppress women’s learning. Meanwhile, this narrative ignores historical realities. The first university in the world—Al-Qarawiyyin in Morocco—was founded by a Muslim woman, Fatima al-Fihri, in 859 AD. Education is highly valued in many Muslim communities, and yet, the West chooses to overlook this fact.

This selectiveness towards what to report and what to ask shows the West’s tendency to view feminism through a lens of privilege rather than genuine empathy.

Yes, some women don’t have access to education, but how can that be the focus if women are getting killed and can barely survive? Both of the causes that Western feminists fight for are worthy, but the understanding of these issues is distorted to the point of irony. Education is important, but so is being safe and surviving to have a better future for themselves and their family. It wasn’t until the war in Gaza started that women in Gaza stopped having access to education. To fight for feminism, we can’t ignore the root cause of the issues. We can’t be selective about what to talk about because it’s “easier.”

Palestinian women want freedom from violence. They want peace. They want shelters, homes, healthcare, sanitation, and safe births. They want a voice, representation, and acknowledgment of their struggle. Once these have been solved, they can then focus on education.

While personal freedom and equal access to education that the West prioritizes are important, it’s difficult to make progress globally if the women who fight for women’s rights disregard the lived experience and the threat to the lives and health of women who aren’t in the West.

When we talk about feminism and the struggle for freedom, equality, and justice, we need to speak about the struggle for all women at all times without upholding a double standard and not at the expense of other women.

We need women from all over the world to get the same attention as the women who speak in the West.

Their voices also need to be heard.