Despite what the media says, Japanese Juvenile Law is necessary

April 16, 2020

While juvenile delinquents in Japan have decreased from approximately 350,000 delinquents to 70,000 since the late 1980s, a survey constructed by the Cabinet House in 2015 shows that 80% of the public believes that it has been the opposite. Similarly in the same survey, when asked if they believe that these crimes are getting more violent, over 60% answered yes. Because of this inaccurate notion, the majority have demanded for harsher or even the abolition of the Japanese Juvenile Law, and this can impact negatively on our public security.

So why is it that so many people believe that there has been an upward trend in juvenile crimes? Firstly, we must consider where these people are getting information on crimes as well as public security. According to an opinion poll run by the Cabinet House in 2006, when asked about the sources they use to get information on security, 95.5% of participants answered TV or Radio, 81.1% answered Newspapers, 38.4% answered conversations with family and friends and lastly 21.6% percent answered the internet. Although more people would get information from the internet if this survey was done today, we can estimate that the majority still gets information about security from either TV, Radio, or newspapers. This means that the Japanese mass media must be responsible for the public thinking juvenile crime rates are increasing when it is not.

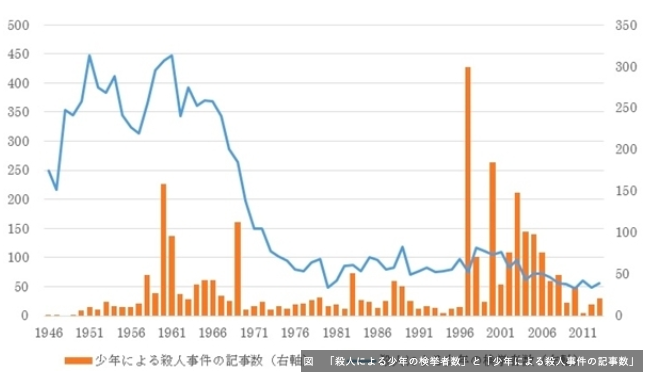

According to a report by Nagasaki University, while the number of juvenile delinquents convicted in the recent few years does not even make up a third of the number of juvenile delinquents from post-WW2 to the 1960s, articles published on this matter are increasing. Nobuo Ikeda, a former NHK ( Japanese National Broadcasting System ) director once said that this police news is easier to report because it is sensational enough to engage with the reader, but won’t cause problems with the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications or with the commercial sponsors like political news. Unfortunately, articles reporting on more controversial, dangerous, or graphic content become sensational and therefore sell more, and this is why the media continues to report on juvenile crimes even when they are decreasing.

Until the late 1990s, the media did not focus on juvenile crimes as much as they do today, and when they did report on these cases, they usually searched for problems in society that led to the crime. This includes inequality, teen labor, poverty, and the fiercely competitive university entrance system.

The Kobe Child Murders of 1997 turned the tide. The Kobe Child Murders were committed by an 11-year-old boy under the alias Seito Sakakibara, who was guilty of several assaults, two homicides, and the decapitation of one of his victims. Unlike the crimes committed by juveniles in the past, this was unexplainable. Sakakibara was not struggling with poverty nor was he a victim of abusive parents. This incomprehensibility grabbed the media’s attention. For this one case only, Asahi Newspaper reported 261 times, Yomiuri Newspaper 136 times and Mainichi Newspaper 290 times.

There was similar media attention for another juvenile crime that came afterward: the Tochigi Female Teacher Murder and the Sasebo School Girl murder. In 2015, there was another homicide case caused by a juvenile criminal known as the Murder of Ryota Umemura. Not only did major newspapers cover this case on their front pages for over a month, but with the addition of social media, this case received an immense amount of public attention.

When a weekly magazine, Shukan Shincho released the perpetrator’s face and his real name against Juvenile Law, the public praised them and created a petition on social media to get him on death row. The homicide occurred on February 25, 2015 and by March 7 of the same year, more than 2,000 people signed the petition. Seeing the attention Shincho received, their rival magazine, Shukan Bunshu, published an article demanding a stricter reform of the Juvenile Law. On a television debate program, when tv anchors and guests discussed the abolition of the Juvenile Law, fifteen votes agreed to the motion and only ten disagreed. Correspondingly, when the show conducted a poll on the same motion with their viewers via the internet, an overwhelming 90% agreed. In addition, a poll conducted by Yahoo states that 94% of participants agreed to a harsher reform of the Juvenile Law.

Graph describing the correlation of the articles published on Juvenile crimes ( orange ) and the actual number of cases ( blue ).

However, these sensational crimes committed by juveniles are a very small minority in comparison to the broader range of illegal acts committed by minors. According to the White Paper on Crime constructed by the Ministry of Justice in 2019, out of the 30,939 Juvenile delinquents that were convicted in 2018, those charged with homicide were only 38, covering 0.1 percent. The Japanese Juvenile Law protects these delinquents’ identity and re-educates them so they can return to society without causing further trouble. With the media focusing on rare violent crimes due to selection bias, rather than immediately accusing the Juvenile Law, we must take a step back and think about what is best for the delinquents themselves and our social security in the long run.

To begin with, the Japanese juvenile System ( Shōnen hō ) established in 1948 as Law 168, is quite complex. According to the juvenile Act Article 2, the term “Shōnen” refers to a person under the age of 20. Hikō shōnen, a Japanese word for juvenile delinquent, refers to a youth that has been convicted of a crime or has confessed to a crime.

The Japanese Juvenile Law is absolutely necessary in order to prevent further juvenile delinquencies because the system provides education for the minors, and protection of their identity which allows them to safely return to society for the most part. There seems to be a misunderstanding that Juvenile Law is established to punish delinquents. On the contrary, Juvenile Act Article 2, states that “The purpose of this law is to train juvenile delinquents to have a healthy development, take special measures on juvenile cases as well as conduct personality correction and environmental adjustment related supervision.” This is crucial as the majority of juvenile delinquents haven’t received the full three-year Japanese high-school education.

Mitsuyoshi Yanami, professor at the Graduate School of Science Education constructed a survey for junior-high and high school delinquents on their academic achievements. The data showed that 80% of the junior high juvenile delinquents and 78% of the high-school delinquents answered that their grades were on the lower side in their class. To add, approximately 80% of both high-school and junior high school delinquents combined answered that they do not study at home.

In Japanese society where one’s academic background is heavily valued, it can be difficult for junior-high school graduates to get a job compared to high school and university graduates. Furthermore, Employment plays a major role in the probability of committing a second offense. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, recorded the job acceptance rate for both high school graduates and junior high graduates at a public employment security office in 2018. The job recruitment rate for high school graduates was 99.4% and junior high school graduates were 81.2%.

In addition, abolishing the Japanese juvenile system means that the identity of these delinquents will be exposed. An employer would not want someone with a juvenile offense background when there are other options. It would be extremely difficult for delinquents to return to society when their faces and names are marked by misbehavior, minimal education, and a few-year gap on their resume.

In 2017, the Ministry of Justice has investigated the second-offense rate for both delinquents on probation and delinquents who have been temporarily discharged. For delinquents on probation, 55.7% were unemployed, 15.5% were employed and 10.6% were students. Similarly, for delinquents who have been temporarily discharged, 44.8% were unemployed, 16.3% were employed and 8.5% were students. This shows that if Juvenile Law was to be abolished and delinquents did not receive a proper education, after discharge, it would be hard for them to find a stable paying job, possibly leading to another offense. This not only affects public security but has social costs as well. Increased second offense means more investments poured into the operation of prisons, which come from taxes. Therefore, in the worst-case scenario, banning the Japanese Juvenile Law can lead to an increase in taxes.

However, despite the many benefits of the Japanese Juvenile Law, there is still room for reform. Firstly, the rare delinquents with a low probability of rehabilitation such as ones convicted of violent crimes should be prosecuted under an adult court. In fact, this has been done once to an 18-year-old that was convicted of rape, abduction, confinement, and murder. He was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment at the Tokyo High Court, which is the highest penalty one can receive in Japan if not on the death row.

Secondly, in addition to the lack of education juvenile delinquents have, according to the book ケーキの切れない非行少年たち (translated to “Juvenile delinquents that are unable to cut cake”) many Japanese delinquents suffer from low IQs ranging from 70 to 84, leading to below-average cognitive function. This eye-catching title represents how some juvenile delinquents were unable to cut a cake into thirds when asked.

Unable to keep up with the rest of their classmates, these delinquents sometimes faced bullying or exclusion, leading to less motivation in their studies and eventually stopped attending school. This cycle makes the adolescent with a below-average cognitive function vulnerable to committing more crimes. According to writer and child psychiatrist who worked in both psychiatric hospitals and medical juvenile reformatory Koji Miyaguchi, these juvenile delinquents require special support and guidance rather than providing the education given at ordinary schools in order to end the cycle so they can keep up with the work and fully understand what is being taught.

Thirdly, the Shōnen hō should be more involved in supporting life after discharge. Juvenile delinquents usually come from unfortunate circumstances such as minimum academic background, parental abuse, poor mental health, and low-income households. According to Teikyo University’s comprehensive research on the causes of juvenile delinquency, juvenile offenders are more likely to come from a low-income upbringing. This is an essential factor when considering juvenile crimes because adolescents, mostly boys, are extremely vulnerable to being approached by other former juvenile delinquents, motorcycle gangs and even the yakuza and hangure gangs (people that are not official members of yakuza yet perpetrate crimes such as remittance fraud).

Over 40% of delinquent inmates come from single-mother households, and 31.8% of the male inmates and 51.4% of the female inmates experienced parental abuse. Because of these factors, the Japanese juvenile system should make sure that their juvenile delinquents are safe and that they are employed by a stable job before their release.

The Japanese Juvenile Law still has significant room for reform. However, since they provide a chance for youth who travelled down the wrong path to be re-educated and return to society and prevent second offenses, the law is necessary — despite what the public says.