In 2017, Japan’s “Word of the Year” award had two winners. The first, “Instagrammable (インスタ映え), was an obvious winner, given the surging popularity of Instagram at the time. The second winner, Sontaku (忖度), may not have been a trendy social media phrase, but the word captured a nuanced aspect of Japanese culture, making it equally deserving of the prestigious award.

Like many Japanese words, sontaku has no direct English translation. In Japan, it is seen as a certain value to gauge the needs of somebody without having to be told directly. While some may refer to “reading the room” as a similar concept, sontaku goes beyond just simply reading the social cues in a situation. It emphasizes the importance of taking action in a way that is considerate to a person’s expectations, thoughts, and feelings.

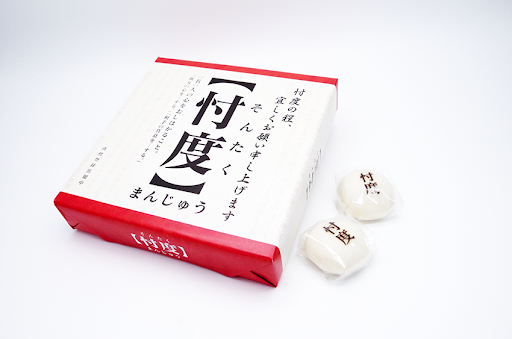

A small manufacturing company in Osaka received the “Word of the Year” award for sontaku in 2017. The Japanese word plastered on their red-bean-filled steamed buns had gained widespread popularity.

“Considering a person’s perspective and understanding their intentions is important in communication between individuals,” commented the Osaka production manager in an interview with The Mainichi Shimbun. “Sontaku can actually be viewed as a positive value that is unique to Japanese people.”

Originating from ancient Chinese poetry, the word sontaku made its way into Japanese society as far back as the Heian period. The word had only carried a vague meaning of compassion, however, and was rarely used.

Meanwhile, words such as omoiyari (思いやり) and omotenashi (おもてなし) served as alternatives to describe Japan’s hospitality and social dynamics for centuries. Acting for the collective benefit of others is deemed as a positive aspect in Japanese culture, and sontaku is a word that expresses Japan’s considerate nature as much as the other words do.

Yet, in recent years, sontaku is widely known to have negative connotations. Frequently appearing in business or government settings, there is an assumption made that sontaku gives people in power an unfair advantage.

What shifted this word from representing thoughtfulness to becoming associated with controversy?

Image credit: L26, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Moritomo Gakuen Scandal came to light in early 2017, as Asahi Shimbun disclosed a controversial land deal between a Japanese private school operator and the Japanese government. Moritomo Gakuen was a private elementary school constructed in Osaka prefecture, with the principal known to have close ties with the wife of the then-Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe. Aware of the relationship, the government land was sold at a significantly discounted price — an approximate discount of 819 million yen — by the Local Finance Bureau.

While Prime Minister Abe’s close associates accepted the discount, the reality is that neither he nor the principal had asked for such a concession. But this is where sontaku comes into play — the Local Finance Bureau had surmised the feelings of both the principal and the Prime Minister, causing them to act in a way that would unethically benefit the relationship of the two figures.

With allegations of favoritism, the scandal led to political and public outrage. Prime Minister Abe claimed that he had never asked for a discount, and that he would resign as Prime Minister if he and his wife really had ties with the Moritomo Gakuen scandal. In reaction to Prime Minister Abe’s comment, Director-General Sagawa of the Ministry of Finance urgently ordered his staff to alter the documents for a cover-up.

This is the second performance of sontaku. Again, Prime Minister Abe had never asked Sagawa for a cover-up of the documents. Nevertheless, Sagawa took into consideration the backlash Prime Minister Abe may face, and decided to act on inference. His actions were corrupt, and ultimately raised ethical issues concerning the transparency of the Japanese government.

Jeffery Kingston, Director of Asian Studies at Temple University, describes sontaku — sensing a superior’s wishes and acting without explicit directions — as a loophole and a perfect way to avoid responsibility. “Superiors can say ‘I didn’t order it,’ and those lower down can say, ‘I’m following orders,’” he said in an article published by Reuters.

Though the concept of sontaku gained widespread recognition through the Moritomo Gakuen Scandal, it had seemed as though the flame died down in a couple of years. The word sontaku was used more frequently amongst Japanese people, but it had become more of a neutral term rather than something negative.

The flame re-ignited this year, with yet another scandal, this time unfolding within the Japanese media industry.

In 2023, four years after his death, it was revealed that Johnny Kitagawa — the founder of a well-known Japanese talent agency — had committed sexual abuse against hundreds of boys in his idol agency over the course of 40 years. Despite the court officially recognizing Kitagawa’s abuse in 1999, all Japanese media outlets remained silent about the case. The allegations were buried in the dark until a recent BBC documentary brought the incident to attention.

Why did the Japanese media refrain from reporting Kitagawa’s sexual abuse allegations for decades? An NHK feature program interviewed multiple former NHK program staff to answer this very question. “People would think you’re out of your mind if you stopped using Kitawagawa’s idol groups due to legal reasons,” commented a former NHK music producer. “If we don’t use idol groups from Kitagawa’s agencies, our TV programs would stop and shows won’t be possible.”

While people were aware of the allegations within the media industry, many had avoided reporting the matter due to the powerful influence of Johnny Kitagawa. They had gauged the feelings of Kitagawa himself, and decisively chose to keep silent about the issue — a precise example of sontaku being acted out in the industry.

The Asahi Shimbun interviewed a TV producer who claimed: “Many executives at the agency engage in negotiations as part of company affairs, creating an atmosphere of sontaku.” Protecting the superior’s feelings was unethical, and with the pressure to succeed in the media industry, actions of sontaku towards Kitagawa’s agency had been inevitable.

Both the Japanese government and media have been caught up in major controversies over the years, with sontaku at the center of it all. After the various scandals within Japanese industries, people are beginning to associate sontaku to unethical behaviors.

Despite all the corruption, sontaku still encompasses multiple definitions. Alternatively, one could perceive sontaku as a valuable aspect of Japanese culture, representing a form of compassion. The red-bean steamed buns were initially created to promote the positive aspects of this unique value. But countless scandals have marred the true meaning of the word, illustrating sontaku as more of what it is not; as of now, the Japanese value has lost respect. It may be time to foster a renewed understanding of sontaku, with all its multifaceted complexities.