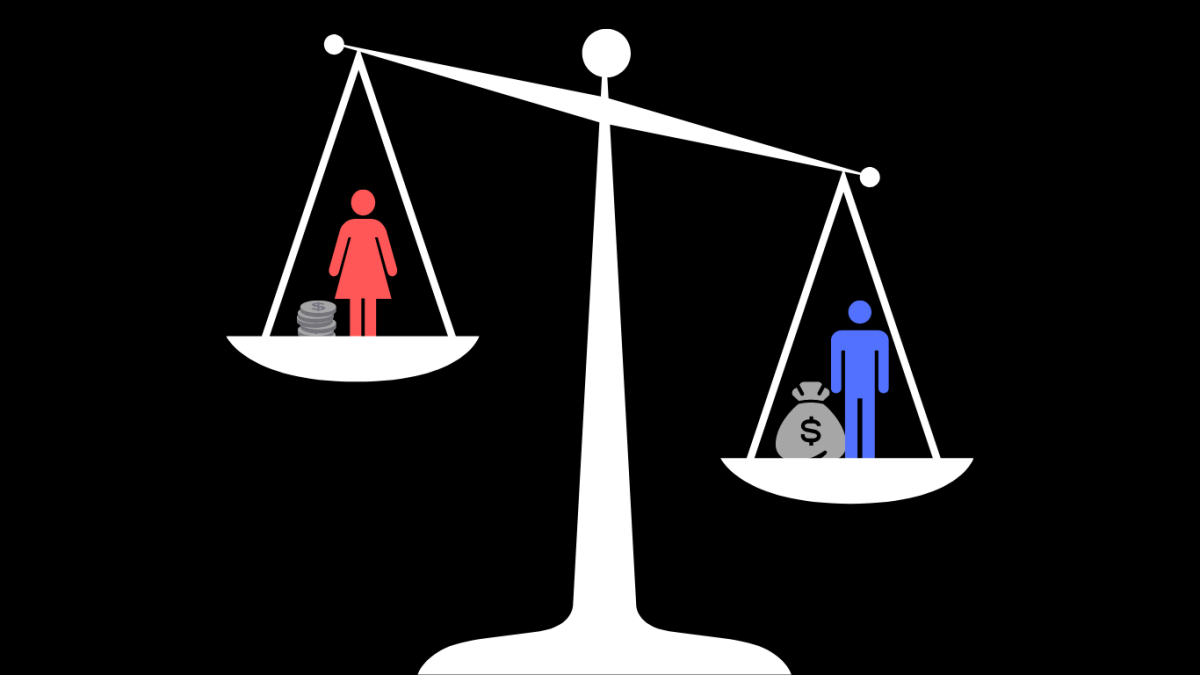

We’ve all heard of the gender pay gap – the fact that women are paid less than men for doing the same work. But the bigger, less talked about issue is the gender wealth gap. Wealth measures the value of all assets of worth owned by a person, including investments, savings, debt, and inheritances – all of which are huge contributors to a person’s long-term financial stability and power. Wealth is a strong indicator of future wealth, because it “takes money to make money,” which means that wealth can compound and grow over time when placed into reliable long-term investments.

Women in the US earn around 82 cents for every dollar their male counterparts earn. This hasn’t changed much for over two decades. However, the wealth gap is much bigger. In 2021, American families headed by women owned just 55 cents in median wealth for every dollar a family headed by a male. Unmarried women owned only 34 cents for every dollar an unmarried man owned.

The income gap is a leading factor contributing to the wealth gap, because a lower salary limits the ability to build wealth. One reason for the income gap is that the highest-paying fields, such as the financial services industry, tend to attract fewer women. Professor Kristen Collett-Shmitt, Associate Dean at the Mendoza College of Business, finds that the gender imbalance in these fields causes women to leave, and this only perpetuates the imbalance.

“We see [female] students choosing to do finance, but the rate at which they stop doing finance and maybe switch to accounting or business analytics, where the fields are a little more diverse, is pretty high. They’re going to their classes and seeing that the jobs they will have will be male-dominated.” One advanced investment management class that Professor Collett-Schmitt teaches, which has roughly 30 students, has only 3 women.

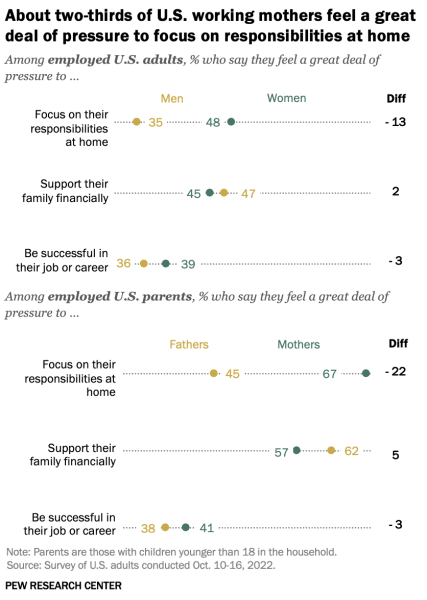

Another contributing factor to the imbalance of women in high-paying roles is that women have more trade-offs when it comes to pursuing more advanced degrees and a demanding career. Often, women are forced to choose between advancing their careers and education or having a family.

However, even in the same role with the same qualifications, women earn less due to long-standing biases.

“Women are often penalized in the workplace for asking for what they deserve, because it’s counter to the traditional stereotype that we associate with women, who are often thought of as compromising in the workplace,” said Professor Collett-Shmitt.

Additionally, women face barriers when accessing better jobs and promotional opportunities. Since upper-level positions in most industries are dominated by men, “women have a more difficult time networking with men at upper-level positions,” said Professor Collett-Schmitt. “If networking and meeting other professionals help with promotional opportunities that lead to increases in income, then women are challenged.”

However, wealth-building entails more than simply earning a high salary. Wealth depends more on how much you save and what you do with those savings. According to Aviva, 37% of women do not invest while for men, it is 24%. While the stock markets have historically gained 10% per year, savings accounts earn little interest. And with inflation, the purchasing power of money in savings decreases over the years. If women keep their money in savings accounts rather than investments, they aren’t growing their wealth at the same rate as their male counterparts.

One reason that women invest less is because they have less exposure to investing.

“Investing is often something that’s seen as a male activity, and so it’s just something that’s more part of the male culture. People talk to them about it and they gain exposure to it even at a young age,” said Professor Carl Ackermann who teaches financial management and personal finance at the University of Notre Dame.

Women are often assumed to inherently be more risk-averse than men, but research has shown that the difference in risk taking has more to do with knowledge and experience than gender differences. An academic study of 2,000 mutual fund investors showed that women took fewer risks than men. Yet, when the results were adjusted to take investing knowledge into account, the willingness of women to take risks was closer to that of men.

Professor Ackermann agrees that the risk aversion stems from knowledge and not gender differences. “Everyone as they get more experience becomes more comfortable taking risks. I know that’s how it worked for me when I started out, and then I realized, sure it’s important to take on volatility to get excellent returns over time,” said Professor Ackermann. “I adjusted to that, and a woman’s adjustment wouldn’t be any different. I think it’s just a matter of gaining more knowledge and experience and therefore becoming more and more comfortable. Once that happens, the result is the same, whether that person is male or female.”

Women also face more barriers when accessing financial institutions. Professor Collett-Shmitt recalls her experience buying a car: “My husband and I went into the financial discussion together, and yet the individual was primarily speaking to him. Because of that bias, women miss opportunities to become more active in investment and financial planning.” Not only are women dismissed, but they are frequently denied opportunities that would lead to wealth-building, such as taking a loan from a bank, due to gender bias. A randomized study in Chile found that when making equivalent loan requests, women were 18.3% less likely to be approved than men.

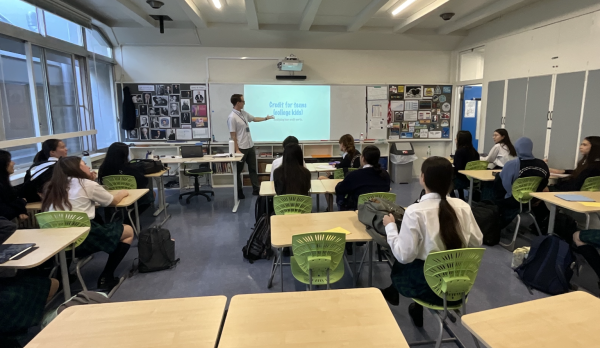

Institutional change and awareness of social biases are essential to bridging the gender wealth gap, but small-scale financial education programs for women, especially at the high school level, can also be key.

“I think financial education programs at high schools should be nationally mandated,” said Professor Ackermann. “The problem with personal financial education is that no segment of the educational system has taken control of it. There’s a little of it at the college level, but not everyone goes to college. So, the right place for it is in high school.”

Once women have the knowledge to start investing, they are, on average, better investors than men. According to research from Fidelity Investments, women investors tend to achieve more positive returns and outperform men. This is because men tend to make more trades, which reduces their overall returns, while women tend to hold their investments over the long-term.

Even though the world of investing can seem daunting, Professor Collett-Schmitt advises all women to start small.

“Start with a small amount. What’s at stake is a small amount of money, and the purpose is not to become super wealthy. The purpose is to discover something new. It’s empowering.”