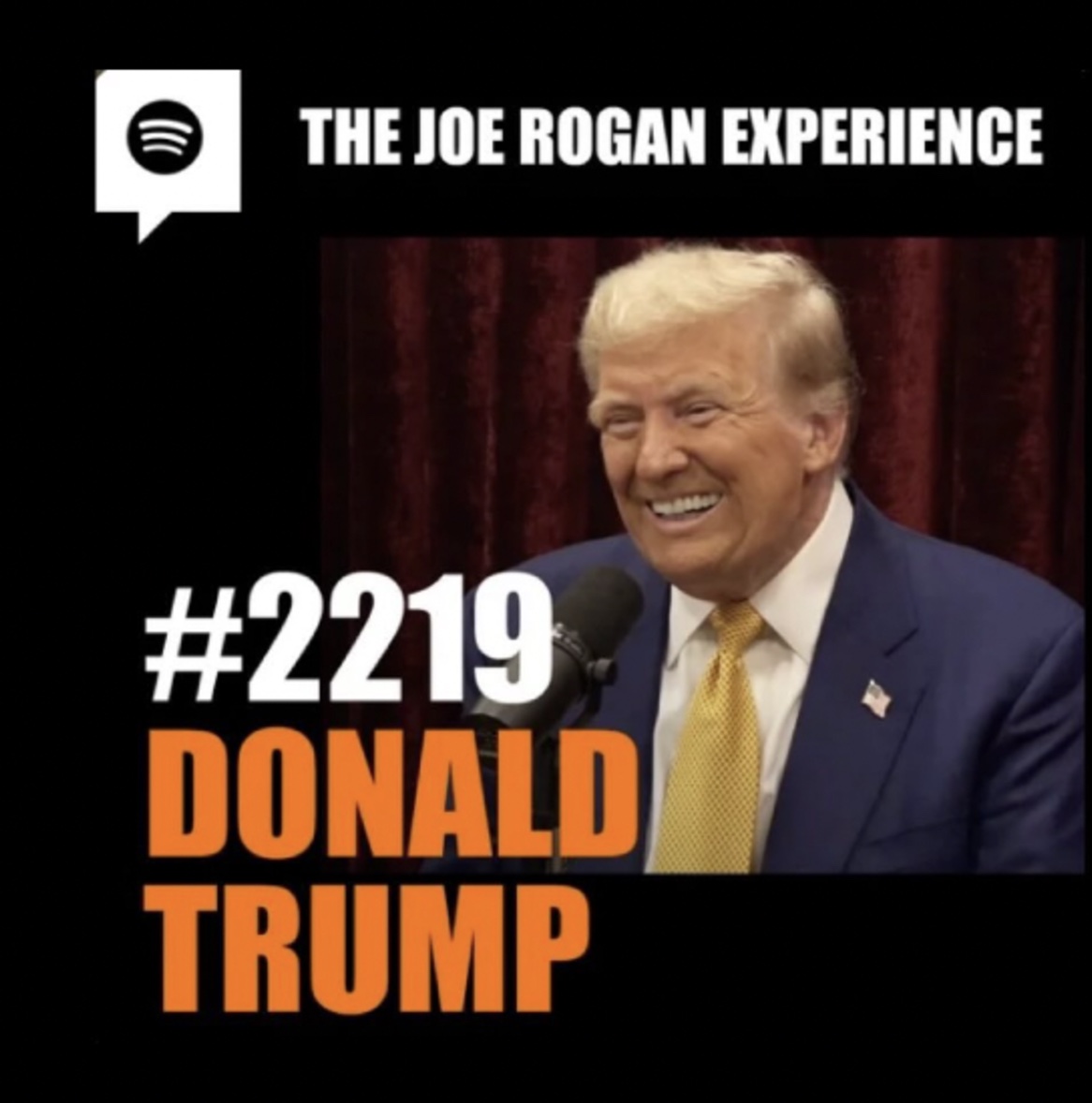

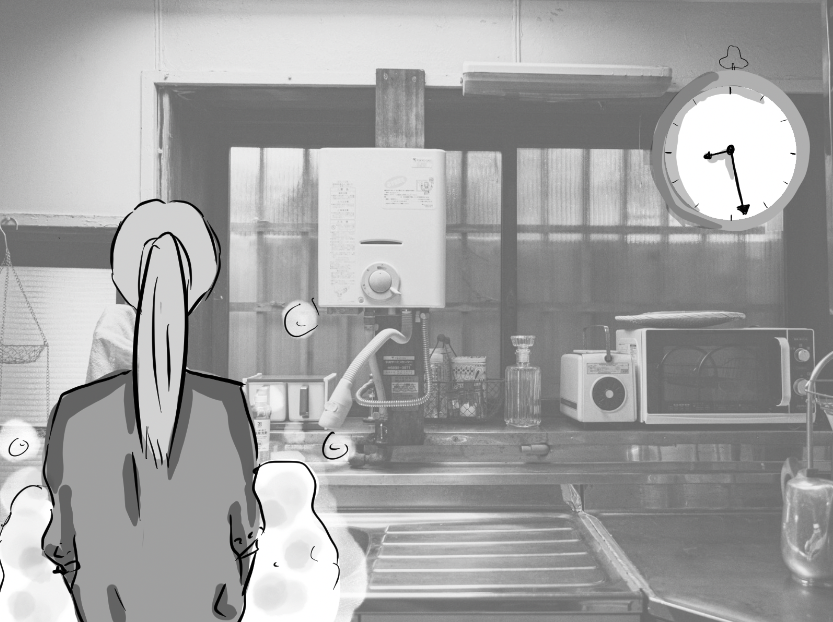

A Japanese lesbian couple was granted refugee status in Canada in September of 2023 after facing widespread discrimination in their workplace and community. Despite the couple, Eri and Hana, obtaining a partnership certificate through Japan’s same-sex partnership system, they felt as though they were not granted the same protections as other heterosexual married couples. The Canadian immigration authorities granted refugee status to Eri and Hana after declaring that the “rights of women and sexual minorities were not sufficiently protected in Japan.” In an interview with Pride Japan, the couple mentioned “There are many LGBTQ people and women living with the same struggles as us, and we wanted to raise our voices to the Japanese government and its people.”

Though it is rare for Japanese citizens to seek asylum abroad, that doesn’t mean it never occurs — in data published by the UNHCR, 144 individuals sought asylum from Japan in 2023, and 48 were granted refugee status. While specific reasons behind these asylum requests are unclear, it is evident that these individuals feel unwilling or even unable to remain in Japan.

The case of Eri and Hana highlights how Japanese society is not ready to fully accept members of the LGBTQ+ community, with some still viewing them through a lens of scrutiny. Japan is widely regarded as a safe nation, but this perception masks a deeper issue: the country’s intolerance towards those who are simply different from Japanese mainstream society.

These internal issues are mirrored in Japan’s low refugee acceptance and restrictive application process, both of which are often criticized internationally. In 2023, approximately 14,000 individuals applied for refugee status, and 303 were granted asylum. While this marks Japan’s highest number of accepted refugees, the overall acceptance rate remains a mere 2%.

To put this into perspective, a comparison can be drawn between Japan and Germany — two nations with similar GDP levels. Germany, which has become the third largest refugee-hosting country in the world, accepted 51% of asylum applications in 2023. In stark contrast, Japan ranks at the bottom of the G7 and has been repeatedly urged by the UN Human Rights Council to address issues of refugee and migrant discrimination.

While the 1951 Refugee Convention provides a general definition of who qualifies as a refugee, it leaves room for broad interpretation and lacks any specified criteria. Japan applies a particularly strict interpretation, making the application process much more difficult. For instance, Japan defines “persecution” as a direct threat to an individual’s life. Unless someone is personally targeted by their government, they are often not recognized as a refugee.

Furthermore, refugees must also meet strict standards to prove they cannot safely return to their home country. Afshin, who fled from Iran to Japan to escape severe persecution, faced numerous life-threatening incidents, including being held at gunpoint by Iranian police in a park. After arriving in Japan, Afshin applied for refugee status four times for several years. He was, however, rejected by the Japanese immigration office for not providing “photographic evidence” of the events, despite it being virtually impossible for a refugee to flee with any solid proof of their persecution. Lacking a refugee status, Afshin was detained by the Japanese government due to a visa overstay.

The Japanese government tends to view refugees not as individuals in need of protection, but as people to be controlled and managed. This extremely systematized approach led to the struggles refugees in Japan face today.

The Japanese government has always taken a critical stance on refugees, and so have the Japanese people. According to a public opinion survey, 54.6% of the people acknowledged that Japan’s refugee recognition rate is extremely low. However, when asked if “Japan should actively accept refugees” only 24% of the people either agreed or somewhat agreed on the matter.

One of the primary concerns is security, as there are fears that admitting refugees could lead to an increase in crime, terrorism, or a deterioration in public safety. These security issues are not unique to Japan; other host nations also share similar apprehensions. Despite the lack of statistical evidence linking refugees to an increase in crime in specific regions, the stereotypes and fears ingrained in Japanese society are quite difficult to overcome.

In a survey by the University of Tokyo, over 60% of the respondents said that a rise in the number of immigrants would “lead to a spike in crime rates” and “jeopardize security and order.” Based on this data, Kikuko Nagayoshi, an associate professor at the Institute of Social Science, explained that “crimes tend to get a lot of attention, especially in the media” and that “these media almost always draw attention to the ‘foreign’ aspect or the nationalities reporting on crimes committed by non-Japanese.” Nagayoshi explains that, as a result, “foreign nationals tend to be associated with crimes, fostering negative stereotypes.”

A Kurdish population of approximately 3,000 individuals in the Tokyo area has been facing such discrimination from their surrounding Japanese community. The Asahi Shimbun reported in April 2024, Japanese demonstrators organized a widespread protest against the Kurdish population, expressing that the Kurdish people should leave their city immediately. The Kurdish people are one of the largest displaced ethnic groups, having endured long-standing repression by the Turkish government. Since 2011, around 50,000 Kurdish immigrants have been recognized as refugees globally. However, following multiple incidents caused by certain members of the Kurdish community in Japan, the entire group has come under scrutiny.

There remains a divide between the Japanese people and those labeled as “social outcasts,” fueled by fears of deteriorating public safety and ingrained societal stereotypes; this shouldn’t be normalized. Immigrants such as the Kurdish people may be a source of benefit to society—if integrated into the workforce, refugees could help mitigate Japan’s aging population and contribute to the country’s economy. Nevertheless, Japanese society is hesitant to accept those who come from outside and within, especially when they fail to fully assimilate into the culture, behaviors, and disciplines of the Japanese people. Japan’s concept of unity is often a demand for conformity, and refugees such as Afshin, as well as sexual minorities like Eri and Hana, struggle to fit into these rigid Japanese standards.

Japan is often viewed globally as one of the safest countries in terms of its strong healthcare system, infrastructure, and low crime rates. However, safety extends beyond these measurable factors — it encompasses the ability to respect individual differences, whether it be refugees or sexual minorities, Japanese or non-Japanese. Should Japan truly be considered a safe society if it fails to uphold these values?

To become a more inclusive society, Japan must accept more refugees and should not allow societal discrimination to force their own citizens to seek refuge elsewhere.