The greenwashing crisis

The exploitation of the environmental movement

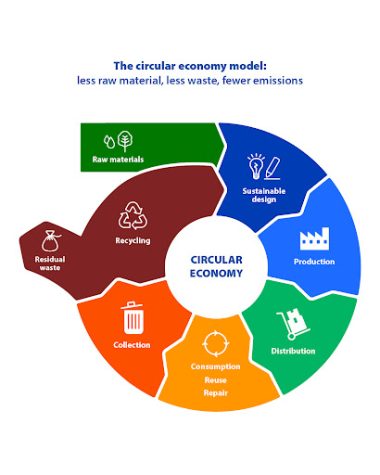

In recent years, product packaging has increasingly become more sustainable. In concern for rising plastic and garbage pollution that contribute to climate change and air pollution, many companies have switched to using eco-friendly packaging using the circular economy model – the concept of reusing material to manufacture something brand new. This minimizes the extraction of raw material as well as the production of plastic. Materials such as biodegradable plastic, paper or cardboard, and recycled fabric have been claimed to be used in skin care products packaging, food packaging, and clothing. But can we trust these corporations to be completely honest about their eco-friendly claims?

In April of 2021, the South Korean beauty brand Innisfree was accused of greenwashing, after releasing a product labeled “Hello, I am Paper Bottle” in seemingly sustainable paper packaging. However, a woman posted photos on social media revealing the shocking truth. She said after using up the Innisfree serum, she cut it open out of curiosity, uncovering a plastic bottle inside. She comments in Korean, “Isn’t that a total greenwash scam?” The woman claims that she had actually picked up a different product, but after seeing that “Hello, I’m Paper Bottle” was minimizing plastic packaging, she purchased it instead. This demonstrates misleading marketing, and how companies are able to easily manipulate environmentally conscious consumers, who fall for greenwashing by purchasing what they think is the greener choice.

This post spread throughout South Korea, and soon Innisfree issued an apology for the “confusion” caused by the misleading label of their beauty product. A spokesperson for Innisfree claimed that “this product is called ‘paper bottle’ to make it easier to explain the role of paper labels wrapping outside of the bottle.” It did not mean the whole bottle was paper material, which may have caused confusion. Instead, the paper layer was supposed to be conveniently removable for recycling and substituted as 51.8% less plastic used compared to previous packaging. “We are deeply sorry for the confusion caused and will try to deliver more accurate information to you,” a spokesperson from Innisfree said to the BBC.

There is a famous brand we all know of that has been accused of greenwashing as well – Starbucks. According to the Crimson White, “In the summer of 2018, Starbucks announced that they plan to globally end their use of plastic straws by 2020.” They announced a new lid design for drinks which would be straw-free, preventing the use of plastic straws. However, people were unsure about Starbucks’s lid design; not only did it look like a sippy cup, but the plastic quality was thicker. Soon afterward, studies discovered that the new lids actually used more plastic than it did in the past (plastic straw and lid combined). Even though Starbucks aims to achieve sustainable designs for beverages, its effort to do so has ultimately been unsuccessful.

To avoid being “greenwashed,” this article written by the International introduces “How to detect “greenwashing” using the T.B.T. rule. The acronym stands for “Transparency”, “Bare minimum”, and “Too good to be true”. The first word, “transparency”, warns consumers to look out for suspiciously vague environmental benefits of a product. Without evidence to support the claims made, it is better to steer clear of purchasing that product. The second phrase, “bare minimum”, is the minimum effort companies put into making a product supposedly sustainable. For example, a clothing brand claiming that they use organic material may be true, but it may only apply to a short selection of clothing. The last phrase, “Too good to be true”, says that if there are exceptional benefits of a product, it is likely that the claims are false. For example, the article says that a “100% ethically sourced, 100% ethically produced sweatshirt for $20” is unrealistically low, when the legitimate price of ethically produced clothing should be around $80.

Not only is the T.B.T. rule useful for determining greenwashing, but you should also be on the lookout for natural colors used in logos and packaging. It is easy to assume an item’s sustainability by only looking at its appearance. Specific colors and textures are implemented in the designing of a product to draw customers into buying it without looking into further detail. Uniqlo announced on Instagram that “the cat-type robot #Doraemon has come from the future and is joining UNIQLO as a global sustainability ambassador,” with a video of Doraemon turning green, switching to “Sustainability Mode.” The green character looks like an encouraging sign of the positive change happening in the clothing industry. However, it can’t be confirmed that Uniqlo is actually making big differences, as the company does not share reports on its supply chain progress. Without updates on how a finished product or service gets to a customer, there is no evidence that the “Sustainability Mode” Doraemon is making a positive change for the environment. However, Uniqlo is not the only company that colors its logos and mascots green to hide dishonest claims.

Companies like Coca-Cola utilize the color green in their packaging to make it seem healthier. In 2013, a new edition of Coca-Cola was introduced, called Coca-Cola “Life”. Unlike other Colas, which are packaged in classic fire engine red, Coca-Cola Life was in pale green. The new beverage reduced calories by 35% by using stevia leaf extract sweetening instead of high fructose corn syrup as a supposedly “healthier” alternative, but both still contained cane sugar. Coca-Cola’s local marketing director said that the aim was to create a taste that was similar to regular coke, but without the artificial sweeteners. This would “help meet its commitment to help tackle Australia’s obesity crisis,” as one in four children are overweight. However, according to The Sydney Morning Herald, “health campaigners said the reduction to 10 teaspoons of sugar in a 600ml bottle made little difference in terms of health impacts.” Products like Coca-Cola Life are not making any huge impact on reducing obesity, so don’t let green packaging trick you. The appearance of a product may entice you. It is crucial to look beyond surface-level information to check authenticity.

It should be noted that not every brand using natural colors or innovating eco-friendly alternatives is greenwashing. There are plenty of brands like Whole Foods and Crisp Salad Works that are environmentally conscious and still use green in their logos and packaging. To avoid being greenwashed, it is important to utilize the T.B.T. rule and watch out for suspicious product design.