COVID-19 daunted humanity— lives were quarantined, hospitalized, and lost. The virus colonized across continents, leaving no corner of the globe untouched. Gratefully, in May 2023, the long-lasting battle ended, and people adapted to their new normal lives.

Subsequently, most people simply dismissed the issue. Most of us did not consider predicting the sequel of this chaotic upheaval that shook the world; we were too busy recovering from it.

Yet, it is undeniable that there will be another pandemic that will ravage us.

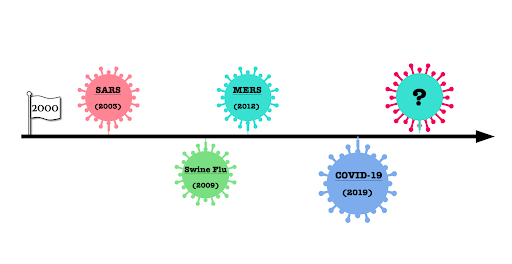

December 31, 2024, marks the fifth anniversary since WHO discovered a virus outbreak in China, later called COVID-19. What’s more, we are already halfway through waiting for the unwanted sequel as, following the trends of previous pandemics and epidemics, these outbreaks happen every 10 years.

Covid-19 was not a surprise attack. Outbreaks of such virulent pandemics have deeper roots in our 21st-century society. Dating back to 2002, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS CoV), an airborne virus that spreads through droplets of saliva, escalated to a global pandemic. According to the UC Berkeley Evolution team, it was caused by a specific strain of the broader coronavirus family (CoV), which was predicted to originate from bat groups in China.

Furthermore, in 2009, the Swine Flu Pandemic (Influenza H1N1), the pig-transmitted respiratory disease, spread internationally from Mexico and was soon declared a pandemic by the WHO. In 2016, the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS‐CoV), was transmitted from dromedary camels and bats and spread through the Middle East. Although declared an epidemic by the WHO, the treatment and vaccines for this (MERS‐CoV) remain undeveloped.

Is it a coincidence that all of these pandemics derive from animals?

Surprisingly, this is not a coincidence. The major causes of such pandemics are our everlasting companions—animals. Animals with contagious microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites can spread directly or indirectly to humans. For instance, animal pathogens can invade our bodies through food, direct contact, the environment, or even small mosquitoes. Small armies of micro creatures colonizing our body simply through touching or breathing can lead to a sudden yet massive explosion—a PANDEMIC!

Zoonosis is any infectious disease that has jumped from a non-human animal to a human. Zoonotic pandemics are on the rise and likely to recur within the next decade. The UNEP presented that 60 percent of known infectious diseases are zoonotic and that the trend is increasing as of 2020, as 75 percent of emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic.

Specifically, COVID-19 was designated a zoonotic disease potentially spread by animal food commodities in Huanan Seafood Wholesale, Wuhan City, China. The epidemiological investigation team from NIH collected swab samples in the market to testify to COVID-19’s positivity. They traced evidence that 33 of the 585 swab samples tested positive. This supported the hypothesis regarding the correlation between initial patients and encounters with the market. It is undoubtedly evident that international and domestically transported animals such as bats, wolves, and snakes, live slaughters, and consumption in the same area would unleash infectious pathogens on humans.

With increasing human contact with animals due to domestication, farmers or raw markets are at risk of spreading new zoonotic viruses. For example, avian influenza, a respiratory disease amongst pasture-raised chickens, can spread to farmers and eventually throughout the entire town if not prevented immediately. Additionally, if farmers sell these infected eggs at markets, the influenza virus will spread rapidly among consumers, triggering an epidemic.

Also, with rapid urbanization and deforestation, animals lose their natural habitats and move closer to humans. In this case, they will likely carry infectious pathogens among wildlife animals and transmit them to humans.

Furthermore, exposure to multiple species of animals in a confined space or laboratory leaks can initiate a chain reaction. Like COVID-19, areas where animals from diverse places gather are at risk of allowing global pathogens to meet. Even worse, tracing a virus’s origin takes time, wasting valuable time limiting further spread. Also, in laboratories, the mixing of genes can lead to the mutation of pathogens. Without enough caution, the researcher can expose the mutated pathogen to society. Even the tiniest mistake in these places where animals are mixed and experimented upon can lead to global sickness.

Deciding who to blame for causing global sickness and chaos is difficult. No one would have purposely started a devastating battle between microorganisms and humanity. Because humans are naturally vulnerable to these transmissions, it is only a matter of time before another animal transmits its pathogens to us.

Humans do not have supernatural powers to control the natural entropy of spreading micropathogens. Thus, understanding the types and causes of pandemics and predicting the next is crucial to preparing for the unwanted sequel. With precise analysis and predictions, society should develop new weapons and shields to fight off sequels of new waves of pandemics invading humans.

It is never too late to take precautions, as this moment marks the fifth anniversary of the outbreak of COVID-19.