In 2004, the social media platform MySpace became the first social media website to reach an active user base of 1 million. Facebook, then known as TheFacebook, reached the same milestone by the end of that same year. Now, twenty years later, approximately 5.24 billion people use social media, and 94.2% of all people with access to the internet use social media every month.

Inevitably, as more people migrate to social networking sites, companies follow, including news companies. Many major English-language newspapers have some kind of online presence, including, but not limited to, Instagram pages or TikTok accounts.

And the youth encounter these news channels: in a survey of 47 International School of the Sacred Heart (ISSH) students, 94.2% of respondents claimed that they encountered news on social media, with 53.2% of respondents saying they encountered “at least one post related to news in one session of scrolling.” It isn’t just in our school where individuals are running into news on social media: a Pew Research Center report found that 52% of TikTok users regularly get their news from the app. This is a figure that has only increased – the report noted that just a few years prior, in 2020, that number was only 22%.

Another trend has emerged: news from social media is no longer a supplement to traditional news; instead, it has begun to overtake it. According to an article by the BBC, “41% of 18 to 24-year-olds say social media is their main source of news (43% across all countries), up from 18% in 2015.” This is accompanied by a decrease in active news consumption, as well as an increase in news avoidance – a 2023 Reuters report found that the percentage of 18 to 24-year-olds using a news website or app has decreased by 29% between 2015 to 2023, and a 2024 report found that “around four in ten” individuals said they “sometimes or often avoid the news.” 44.7% of ISSH respondents selected that they “only engage with the news when it comes across [them] (e.g., scrolling on TikTok or Instagram and a news-related post comes up, someone sends an article to read).”

Grade 11 ISSH student Luna O. is someone who tries to avoid news, and whose primary “source of news is TikTok, literally.” When asked why she doesn’t actively consume news, she wrote, “I don’t have time for it, and I don’t find [news] as one of my biggest concerns.” She finds that the news in the headlines often doesn’t apply to her, so she finds it difficult to take an active interest. “It’s just not like I wake up in the morning and I’m like, ‘I wonder what’s happening in the world?’” Luna believes that her family influences her news-consuming habits, coming from a household where “the news is not something [her] parents talk about,” and an interest in the news has not been actively fostered since she was young. However, she notes that even without actively reading the news, she feels like she gets a good enough grasp on the happenings of the world, as “a lot of people read it and tell [her] about it.” She concedes that this isn’t ideal.

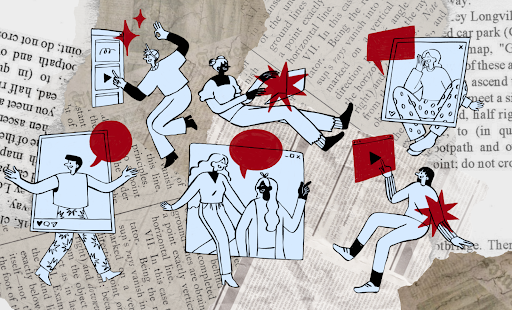

Accompanying these trends of decreased active news consumption is a decrease in thoughtful news interaction and media literacy. A study by the UK government’s Office of Communications (Ofcom) found that, while all respondents could correctly identify “the need to think critically” and “some or all of the ‘current’ buzzwords,” respondents had difficulty distinguishing between news and advertisements/entertainment and “articulating what these [buzzwords] mean, or might look like in practice.” Despite their acknowledgement of the necessity of critical thinking, the majority of respondents said they didn’t regularly apply it, citing that it is “too much effort” or putting their confidence in an “inherent ability to gauge the trustworthiness of the news they read.”

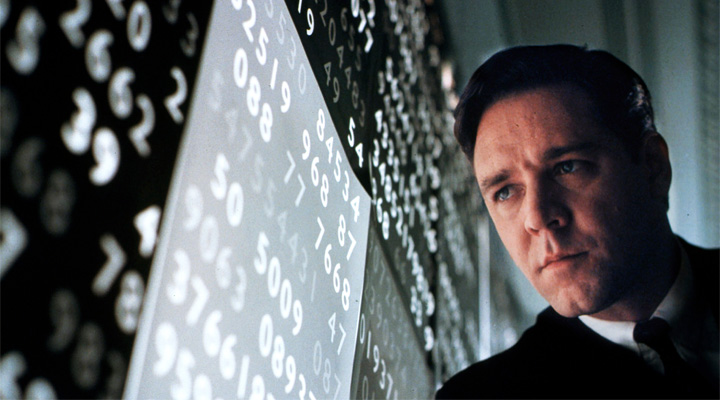

The study posits that part of this could be attributed to the devices often used for social media: the way that mobile devices work. The touchscreen face of most phones and iPads allows us to get the gratification we get from the release of dopamine when scrolling, and we continue these behaviors to get the same satisfaction. However, in turn, this habit of fast swiping, switching, and scrolling means we often fail to critically evaluate the things we read. Our need for quick satisfaction comes at the expense of our media literacy.

Another such way in which critical thinking is impacted is by the fact that “social media makes things more sensationalized,” according to Nadia A., a grade 11 student.

Sensationalism – the inaccurate presentation of stories to evoke emotion from the audience – is found frequently in journalism, and its use in social media news is prevalent. In our world where there are millions of posts made daily, companies often vie for the attention of their audiences through sensationalist news. These articles are usually successful as they draw readers’ attention and incite a reaction, receiving interaction (e.g., Twitter posts with sensationalist features are more likely to receive a greater amount of likes), and news stories with more interaction are more likely to be pushed by the algorithm, appearing on others’ social media, so the cycle continues. But rampant sensationalism doesn’t just run the risk of disseminating false information: it can also lead to desensitization. Audiences constantly exposed to graphic, explicit, or shocking content are less likely to consider these things “sensational,” as they associate them with “normal.”

Nadia believes that social media’s sensationalization contributes to this desensitization, which can decrease serious consideration of the news. “[My country’s conflict] has been going on for so long, and conflict has become synonymous with [my country],” she said. “Now, people aren’t surprised, and people feel no need to engage [… when] people become desensitized, you don’t critically engage with the [news anymore].” The student noted that this desensitization and lack of thoughtful assessment – especially for her country’s domestic conflict, which doesn’t receive much coverage from Western news outlets – only prolongs conflicts.

The idea that the prevalence of news on social media can lead to desensitization is a shared sentiment amongst ISSH students. Isona B., another junior at ISSH, stated that “[social media news] just pops up without me doing anything.” Despite “ignor[ing] it most of the time, because I don’t want to think about it,” Isona remarked that the large quantity of news she encounters has made her hyper-conscious that “something terrible is happening all the time.” She said this has led to a feeling of “desensitization” and a phlegmatic attitude towards the news: “Why would I bother to find the specifics? Because it’s not going to change.”

When asked if social media news had merits, Isona agreed: “I think it gives people better access to information.” However, she also acknowledged its flaws – “I think that we need more ways for people to get access to news that is unbiased and not trying to generate clicks,” she said.

Most people agree that news is important to society – a study conducted by the Reuters Institute found that in all 19 countries surveyed, “more people say [news is] important for society than unimportant,” and 97.9% of ISSH respondents selected “strongly agree” or “agree” to the statement “news is important at a greater, societal level.” Most people also agree that news is important at a personal level – the same Reuters study found that in 18/19 studied countries, a majority of people say news is personally important to them, and 72.4% of ISSH respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the same statement.

However, just as important is how we consume the news: it is important to critically think about what we read or see online, learn to recognize and actively reject misinformation, and consider which of our habits might be hindering our sensitivity to and understanding of current events.