As you walk through the hallways of our school, it’s hard not to overhear conversations mixed with different languages. A student might mention in Japanese, “Maji yabai (seriously crazy), that test was so hard,” while another comments in Korean, “That movie was so good, geut-cho? (right?)”

Although our international school has a general “English only” rule to promote inclusivity and avoid exclusion, many students naturally slip into their native tongues to better express their thoughts and emotions.

This habit practiced amongst bilingual and multilingual individuals is often referred to as “code switching” or “code mixing.” A term frequently used amongst linguists, code switching is defined as the practice of alternating between two or more languages, dialects, or even accents during a conversation. Nearly all bilingual and multilingual individuals engage in code-switching, a practice that is particularly prevalent amongst students in international schools, where the entire school community consists of diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

At the International School of the Sacred Heart, this trend is clearly evident—according to a survey conducted among the high school student body, 96% consider themselves to be either bilingual or multilingual, and 70% of the students reported that they mix their languages while speaking. When asked why they switch between languages, 85% responded that it helps them express themselves more clearly.

For many students, code-switching serves as a practical communication tool, as many consider mixing languages useful when communicating or articulating their feelings. On the superficial level, this method of code-switching may be a useful communicative strategy. Many students find that alternating between languages enables them to convey their thoughts and emotions with greater nuance and precision. In daily conversations, people may choose to use a language that requires the least effort to express a particular idea, even if that means switching between languages mid-sentence.

Nevertheless, language is not restricted to being a tool for communication and expression. This idea is further emphasized in a study exploring the relationship between language and identity expression, and how code switching can serve as an identity marker among English EFL learners. The study indicates that, because each language has its own set of expressions in which people interpret the world in similar ways, language becomes a fundamental part of one’s social and cultural identity. According to the study, language “basically gives a sense of meaning of the world and self to every individual.” Thus, language is not just a reflection of individual thought, but fosters a sense of belonging within a broader community.

The significance of code-switching in social settings can also be understood through the Social Identity Theory, developed by Henri Tajfel and John Turner in the 1970s. The theory suggests that individuals derive a significant part of their identity from social groups. In the context of code-switching, when individuals switch languages, they often attempt to align themselves with a particular social group or societal norm. By switching languages, individuals seek acceptance and harmony within a particular group of people.

This trend is also present among Sacred Heart high school students, where 77% of the respondents felt that they either do or somewhat act differently depending on the language they were using. Additionally, 80% said that different friend groups influence the extent to which they mix languages. In certain cultural settings, 68% of students said they feel expected to speak a particular language, and even when they are comfortable speaking their own, they notice certain expectations from others. On such occasions, code switching transcends its role as a mere communicative strategy and becomes a means of social and cultural assimilation.

The pressure to assimilate is especially prevalent in international schools, where students are constantly forming and maintaining friendships across cultural boundaries; on top of social expectations, international schools are a unique setting in which a variety of languages, cultures, and customs coexist with one another. In such a diverse environment, students often find that language plays a crucial role in order to maintain interpersonal relationships. A shared language — or even something as small as mentioning a familiar phrase — could foster a sense of familiarity, building a sense of trust and connection.

Karen L, a rising senior, reflects on this experience through her time at Sacred Heart. As an individual who has juggled between speaking English, Mandarin, and Japanese all her life, she often mixes languages based on specific social and cultural situations. “I’ve felt pressured socially to use a certain language in a particular setting,” she claims. During interschool events with other international schools, she felt as though speaking in Japanese was more easily accessible compared to speaking primarily in English. Establishing a certain level of closeness with other students was only attainable through mixing Japanese phrases.

Nevertheless, even as a multilingual student herself, Karen occasionally finds herself caught between languages. “I often feel [that way] because of how everyone around me mixes around between different languages. But, I find that … it is quite hard to picture myself in one without the other.”

As Karen points out, code-switching has become a normalized skill for international school students. Maintaining friendships and blending into social groups in high school makes code-switching an integral part of a bilingual student’s social life.

However, one significant risk of becoming too accustomed to code-switching in international settings is the sense of isolation that can arise once a bilingual or multilingual student steps outside that environment. This experience extends beyond international school students and to every bilingual individual — many exist between cultural boundaries, but feel as though they never fully belong to one.

James S, a high school student at Sacred Heart, echoes this sentiment through his personal experience as a bilingual who is fluent in both Japanese and English. “I feel like I don’t fully belong to the English language because I learned it second … but I also don’t feel like I fully belong to the Japanese language because I’m not Japanese,” he says. As someone who appears ethnically Western, James feels frustrated when people address him in English, often assuming that he doesn’t speak Japanese.

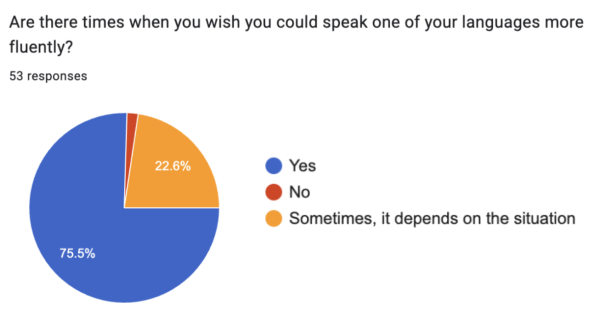

This dilemma is further deepened by the fact that many bilingual and multilingual students struggle to maintain equal proficiency in either of their languages. At Sacred Heart, 76% of student respondents expressed a desire to speak one of their languages more fluently, and 77% reported feeling either entirely or occasionally disconnected from a part of their culture due to language barriers.

Nevertheless, this struggle that bilingual and multilingual students experience is not without deeper value —bilingual and multilingual students understand how difficult it can be to manage multiple languages simultaneously, and they are able to understand this dilemma on a deeper and more personal level; being able to speak multiple languages allows one to develop greater empathy.

Managing multiple languages also allows students to explore and embrace the best of both worlds. Though they may not speak each language with perfect fluency, being able to communicate in two languages—even if at a slightly lower level—enables students to expand their cultural boundaries, offering opportunities and perspectives that monolingual individuals will never experience. For instance, being multilingual means that one is able to share their cultural identity; a student might explain a Japanese concept in Korean to a Korean friend, or discuss an English film in French to their French-speaking classmate, bridging cultures through a shared language.

This is, perhaps, the true meaning of being international. Bilingual and multilingual students in international schools often feel conflicted—constantly code-switching to fit into social circles, but at the expense of their cultural identity. Yet, when seen from another perspective, code-switching becomes a powerful tool for fostering connection and inclusivity.