Too horrifying to be true, too horrifying to question

April 30, 2015

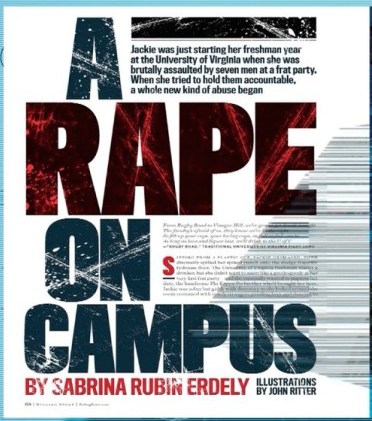

Rolling Stone recently retracted the article “A Rape On Campus.”

Recently, Rolling Stone retracted Sabrina Ederly’s article “A Rape On Campus”, regarding the story of “Jackie”, a student at the University of Virginia who accused boys at a fraternity of brutally raping her. Jackie’s vividly detailed account of her horrific experience immediately went viral and pulled the spotlight onto the serious issue of sexual assault on college campuses. However, many began to suspect that Jackie’s story did not add up. According to the New York Times, the police investigation in Charlottesville, VA., found “no substantive” basis to support Jackie’s description of the assault. In addition, Jackie did not cooperate with the police and refused to be interviewed for the Rolling Stone commissioned Columbia report, which extensively investigated the faults of Ms. Ederly’s article. This report discovered that Ms. Ederly failed to contact three of Jackie’s friends who were quoted in the article, and she admitted herself that she “did not do enough to verify Jackie’s account” and failed to properly question Jackie’s claims due to the sensitivity of the topic. Apart from the journalistic failures of Rolling Stone, the true tragedy of this article is the discreditation of real rape victims on college campuses.

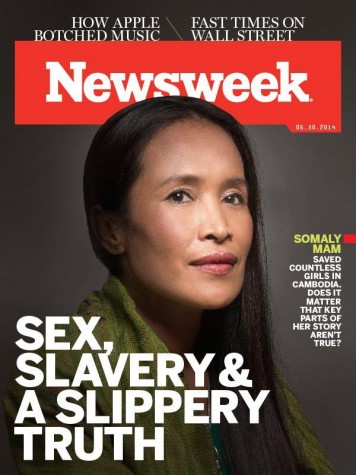

Somaly Mam’s lies were revealed in Newsweek.

Why are we so quick to believe horrific stories? It often seems that the more detailed and unbelievably terrible a story is, the more we unquestioningly eat up every word of it. For example, Somaly Mam, a human rights activist, wrote her memoir, “The Lost Road of Innocence” (2008), in which she claimed that she was a victim of abuse and forced prostitution during her childhood in Cambodia. She also founded AFESIP (Acting for Women in Distressing Situations), an NGO committed to rescuing, housing, and rehabilitating women and children in Southeast Asia who have been victims of sexual exploitation. She also co-founded the Somaly Mam Foundation, a nonprofit organization that supported anti-trafficking groups and helped women and girls who were victims of sexual exploitation, and has received support from various celebrities and political figures. Although her organization was helpful in raising awareness and funds for human trafficking in Cambodia and Southeast Asia, it turns out that Mam lied about much of her story. Despite her claims that she was abused and forced into prostitution at a young age, Newsweek and a documentary by Al Jazeera reported that childhood acquaintances, teachers, and local people in Mam’s village state that she was a “happy, pretty girl” who attended school and lived with her family. According to Newsweek, Mam even hired girls through an audition process and carefully rehearsed them to appear on TV to tell stories of how they were sexually abused. One of Mam’s girls, Meas Ratha, who gave a performance on French TV in 1998, later admitted that she was never a victim of sex trafficking. Despite the mounting evidence against her, Somaly Mam still denies claims that she lied and continues to state that her main purpose is helping the victims of sexual trafficking.

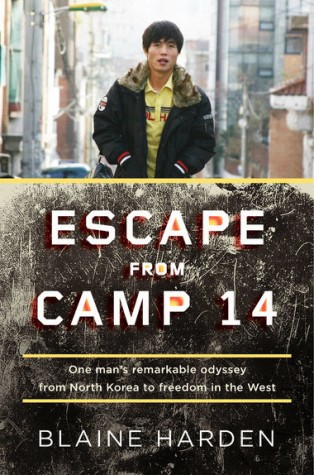

“Escape From Camp 14” recalled the story of Shin Dong-hyuk’s escape from a North Korean prison camp.

Although believability is hard to measure, it seems the more unbelievable the story seems, the more we believe it. In another book, “Escape from Camp 14” (written by Blaine Harden), Shin Dong-hyuk described his dramatic escape from one of North Korea’s most controlled prison camps. According to The Independent, Shin is the only known person to have ever escaped a North Korean camp, and his book contains vivid descriptions of horrible torture and hard labor he endured at the prison. His testimony has been vital to the UN’s campaign to indict Kim Jong-Un for his massive human rights violations. However, Shin has recently admitted that there were “inaccuracies” in his biography. For example, in the book, Shin said he was born and raised in Camp 14 until his escape in 2005. But now, Shin has revealed that when he was six, he, his mother, and his brother were transferred to Camp 18, where he discovered that his mother and brother were planning to escape. He also admitted he had tried to escape from the camp on two separate occasions, and that he endured the worst forms of torture described in the book when he was 20, not when he was 13, as stated in “Escape From Camp 14.” Although these “inaccuracies” are not as extreme as in Somaly Mam’s memoir, the same question remains – why are we so quick to believe such horrific stories without question?

So why are we, as a society, so drawn to the most extreme and horrendous sounding stories? Why are we so morbidly fascinated with being spectators of terrible things that we fail to question the plausibility of the stories? As reported by The New York Times, Emily Renda, a rape survivor working on sexual assault issues at the University of Virginia, said that Rolling Stone was drawn toward the UVA rape case because it was the most extreme story of a campus rape it could find, and the more subtle accounts seemed “not real enough to stand for rape culture. And that is part of the problem.” The problem is that we are drawn to the most extreme stories because they make flashy headlines and interesting breaking news stories. Although it’s terrible, we’re more intrigued by the sex trafficked girls in Cambodia than the thousands of trafficked labor workers. The gruesome details of a man’s escape from North Korea ensure that the memoir will sell because it shocks the readers. And finally, an extreme case of sexual assault on campus is what catapults the problem of campus rape into the public’s eye, rather than the frequent occurrences of sexual assault on campus.