Going beyond music: Vocal Ensemble in the Netherlands

The Vocal Ensembles waits in excitement as they prepare to check in and board the plane.

As the Vocal Ensemble members boarded the plane for the Netherlands, we were overcome with both excitement and fear. Since the Vocal Ensemble trip to Budapest, Hungary in 2013, this was the first time in 5 years that our school would be traveling overseas to participate in a music competition. We knew that it was an honor to have been granted the privilege and that Ms. Horn had worked hard to demonstrate the potential of this year’s vocal ensemble to make use of such an opportunity.

Yet all of us, in our hearts, did not believe we could pull this off. Despite our diligent rehearsals to perfect the dissonant clashes and syncopated rhythms of “Kotoba Asobi Uta”, to memorize the dynamics of “Bogoroditse Devo” and to familiarize ourselves with the correct pronunciation for the lyrics of “Muie Rendera”, we were convinced we would never sound impressive enough to stand out in an International Choral Competition.

This lack of confidence had been infecting us during the weeks leading up to our trip, lowering our motivation and morale. Without a collective sense of pride in our abilities nor a heartfelt connection to our music, our ensemble had begun to fall apart. When we arrived late at night at our hotel in Maastricht, we held one final rehearsal before the evaluation of our performance by the International Jury the following day. That night we realized our performance still lacked something fundamental — because even alongside 17 other members, each of us felt as if we were singing alone.

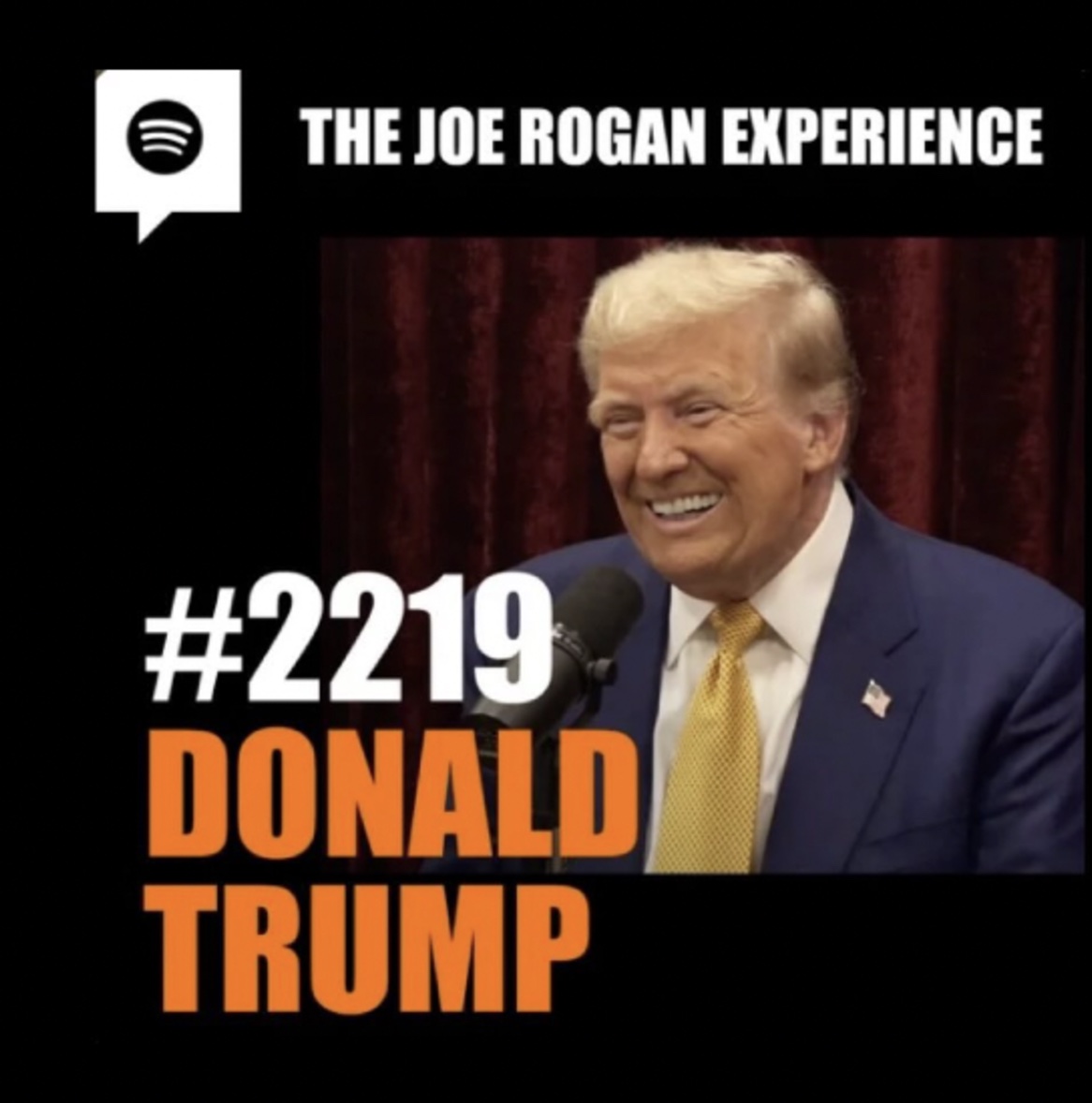

The Vocal Ensemble stands before the International Jury, nervous yet excited to be performing their Evaluation pieces

The next day, we stood intimidated in front of the International Jury composed of choral directors Anders Jalkeus from Sweden, Myguel Santos e Castro from Portugal, and Hans van den Brand from the Netherlands. These three adjudicators were all renowned musicians with years of experience in the choral and instrumental world. Frightened by the unfamiliar stage and the eyes of the jury, we missed the timing for a couple of notes here and there. To our surprise however, they did not pick up on these minor inaccuracies; what they criticized instead was our complete and utter devotion to the written instructions of our sheet music, rather than to the emotions they were meant to inspire.

The jury then gave us the key to break through this barrier that had kept us back all this time: the freedom of expression. Each judge achieved this in different ways for our three songs: The first was for our Rachmaninoff piece, “Bogoroditse”, a prayer to our mothers. We were told by Anders Jalkeus that we were missing intention and that the audience wouldn’t be able to tell that it was a prayer. Anders explained, “This piece written in Russian won’t be understood by the full audience word for word. But singing with the feeling of unified intention and letting that intention reign our facial expression and bodies will surely give some kind of message close to that of prayer to those who listen.”

He told us to stand in a circle, close our eyes, and imagine praying to someone we love. In an instant, the sound changed. This, we would learn, was our first step to unlocking the potential of what we could do with our voices. “What’s difficult is retaining all of that emotion and intention throughout the whole of the piece,” he commented, as we struggled to recreate that sound with our eyes open. He made us sing to the audience and express what we felt through our faces.

The Vocal Ensemble sings their Russian piece “Bogoroditse Devo” with reverence and a sense of prayer in Maastricht’s Sint Janskerk church.

For our next song, a lively Portuguese piece called “Muie Rendera”, we worked with Portuguese adjudicator Myuguel Castro. The first question he asked us was “What does the title of your song mean?”: None of us could answer. In the music world, it is a given that you look at the meaning and definition of the piece name and its lyrics. Ashamed, we listened to him explain that the first lyric of the piece “Ole!” meant “Hello!” to recreate the greetings of Portuguese lace makers and fisher wives in the market. Our realisation of this single translation transformed the way we began the piece as we attempted it a second time, this time making it sound more like a conversation than just a song.

Finally the dance: “Chi la Gagliarda”. This piece is basically an invitation. An invitation to dance the Galliard. Hans van den Brand began to elaborate on the history of the Galliard, and the movement, pulse, and atmosphere of the dance to give us a better feel of what we were trying to convince the audience to do. We repeated the piece again and again, adding dynamic changes to the second part of the piece to mimic the fast and lively Galliarda. With each attempt, the expressions on our face brightened, and our eye contact with the audience became more natural and less forced. Our hearts swelled with pride when, at the end of our final attempt, Hans remarked, “I would definitely dance the Galliard with you!”

The Vocal Ensemble with Swedish Judge Hans van den Brand after their Evaluation rehearsal.

Our performance had impressed the judges, yet it had not moved them. Preoccupied with the technicalities of our vocal execution — our pitches, our dynamics, and our lyrics — we had overlooked the most important part of our music: the story it communicated. For the past few months, we had been rushing nonstop to master all ten songs on our repertoire. Until the judges had stopped to ask us about the purpose and feeling behind our songs, we hadn’t even realized how desperately we needed a moment of reflection to find our answer: a moment to remember that the reason we all joined Vocal Ensemble in the first place was not to win a prize at any competition, but to touch the hearts of our listeners.

Over the course of the three days between our Evaluation Performance and the upcoming Competition, we shifted our focus entirely away from the technicalities of our performance to work instead with the emotions we wanted to convey through it. Ms. Horn and Ms. Mizuno organized a variety of exercises to encourage us to visualize our own interpretations for each piece and to express them through our faces and voices: we pranced around our hotel hallway as we sang the joyful Renaissance piece “Chi La Gagliarda”, sashayed with the spirit of Flamenco dancers for the feisty Spanish number “Las Amarillas”, and immersed ourselves in the sublime image of Norway’s Aurora Borealis upon whose majesty and terrible awesomeness our piece “Northern Lights” by Ola Gjeilo was based.

It was our sudden devotion to the intent behind our music that allowed all of us to, at last, step out of our comfort zones and work together to communicate with our audience. When we were on stage, we were no longer members of the Sacred Heart Vocal Ensemble. We were Portuguese fisher-wives greeting each other at the daily market, the religious of war-torn Russia imploring Mother Mary for salvation, and old women flooded by nostalgic memories of their childhood.