Four takeaways from four weeks of travel in Thailand

April 25, 2019

The summer of my junior year, I broke my summer routine of attending university summer programs and instead decided to spend one month in Thailand with Where There be Dragons, a cultural immersion program. For four weeks, I travelled around Thailand with 11 other students and three instructors, from the lively cities of Chiang Mai and Bangkok, to the isolated villages of Ubon and Karen.

As my instructors highlighted from the day we arrived, we were there as “travellers, not tourists.” That meant phones, computers, and any other form of electronics that would distract us from completely immersing ourselves during our stay were strictly off-limits. I was initially doubtful that I was going to make it. As someone who considered themselves more or less a tech-addict, an entire month without technology seemed like an eternity. Nothing could compare to the anxiety I felt during the five hour plane ride to Suvarnabhumi Airport. And yet now, looking back, I’ve realized that this period of time was a period of tremendous learning in my life. Here are the four main takeaways from my four weeks of travel in Thailand.

Laughter is a universal language.

A home-cooked meal prepared by my homestay mother in Karen Village.

“Bathroom?” Blank stares. “Toilet?” More confused blank stares. The first night I spent with my homestay family in Karen Village was one of the most emotionally overwhelming nights of my life. For one, my family spoke absolutely no English. When we arrived, they welcomed us with friendly smiles and a sincere “Hello!” but that was about it. As for me, the embarrassingly meager list of Thai words that I had picked up prior to my homestay (including “ice cream” and “yes”) unsurprisingly proved to be useless.

After exchanging our hello’s, my homestay sister signaled me to follow her into the kitchen where her mom already was, busy preparing fried eggs and sauteed vegetables. Upon my entrance, the mom signalled me to take a seat on a rectangular wooden block, where I was promptly joined by two family members. For the first several minutes, we ate in silence. My chest pounded as I tried to figure out a way to initiate a conversation. To no one’s surprise, ice cream was not on the menu that night, and I couldn’t use “yes” without being asked a question first. Thankfully, though, the mom took the lead. She saw that I had finished the fried eggs and gave me a thumbs-up gesture. I interpreted this as her asking whether the food was good, so I passionately gave her a thumbs-up back. She then started to laugh, which made both me and my homestay sister laugh. As the room, which was deadly quiet only moments before, filled with laughter, I felt the heaviness in my stomach start to fade away. When the laughter finally died down, my sister turned to me, gave me a thumbs-up gesture again, and said “saeb”. “Saeb,” I repeated after her, guessing that the word meant “good”. For the rest of that evening, we used hand gestures, charades, sound effects, and the overuse of the word “saeb”, to collaboratively work on evening chores.

I learned a lot from my homestay family. For starters, by the end of the homestay, my embarrassingly meager list of Thai words that I arrived with was three pages long. I had mastered the art of charades and reading facial expressions. Hand-gestures became second nature to me. Most importantly, I learned something that I believe could only be truly learned through experience, which was that laughter is a universal language – the ice breaker that not only forms, but strengthens, relationships wherever one may be in the world.

Don’t be Afraid to Bargain.

Booths selling clothes, food, and accessories at the lively Chiang Mai night market.

I could hardly contain my anxiety as I walked down the busy Chiang Mai night market. Never in my life have I had to bargain over the price of a ring! But in Thailand, bargaining is something that is considered standard when shopping for goods. Coming from Tokyo, where the value on the price tag is usually non-negotiable, I was a complete newbie at bargaining. My first two tries were complete failures- the awkwardness was too overwhelming. However, seeing my friends, who were adamantly negotiating back-and-forth over the price of the most ridiculous items, motivated me to keep trying.

I walked over to a fruit stand and confidently picked up a mango skewer. The seller, a younger man wearing a neon colored shirt with the print “DEAD BULL” (a rip-off of the brand “Red Bull”) written across it, gave me a quick glance before mumbling, “200 baht.” I realized upon doing some math in my head that that this was equivalent to 700 yen. “700 yen for a stick of fruit? No way, not today,” I thought as I cleared my throat, looked the man in the eyes, and said, “No, no… 100 baht.” I knew this was still a little pricey for six small pieces of fruit, but the Japanese politeness which was deeply rooted in me kept me from asking for more than a 50% discount. The man glanced up at me again, this time with a “Yikes, she’s not one of those oblivious tourists” looks on his face, before pursing his lips together, forming a little smile, and nodding. “100 baht,” he repeated. As I walked away from the booth with the mango skewer in my hand, I let out a sigh of relief and felt my newfound confidence beginning to grow.

Although I certainly improved my bargaining skills over the course of the month, it wasn’t always easy. Getting out of my comfort zone and asking for a better deal required a type of confidence that I hadn’t necessarily developed living in Japan. Yet, bargaining proved to be a necessary skill in order to make it through the month without running out of cash in the first week.

Stomach Bugs are a Guarantee.

Fresh vegetables on display at a local market in Thailand.

Before taking off to Thailand, I took several trips to the doctors to get vaccinated against all the diseases that I could potentially encounter during my trip. I packed my suitcase with every possible medication, from aspirin to cough drops, and spent hours surfing the web for tips on preventing illness while travelling. So, after weeks of preparation and research, I thought I was set.

Unfortunately, this was quickly disproven during my first week in Thailand. On the first day, one of my instructors said something that made my heart drop to my stomach: “You’re probably all going to get bowel problems sometime during this trip.” My friends and I looked at each other uncomfortably, trying to shake off germs. I didn’t get a good night’s sleep that night, as I kept waking up every few hours convincing myself that I had a stomachache or a fever. The following days, I did everything in my power steer my ill fate in a different direction. Every restaurant I went to, I carefully inspected the ice cubes in the glasses before taking a sip of water. I drenched my hands with hand sanitizer every hour and took vitamin C tablets daily, but sadly, to no avail.

On the third day, the stomachache I assumed was coming from my anxiety turned into more than just a stomachache. It was around this time that the other members in my group also started experiencing illnesses as well. Even though these were certainly not our finest days, were able to laugh it off. “Four down!,” we’d exclaim, as we succumbed one by one.

Although we all fully recovered after several days, I realized that getting sick in another country was not uncommon. The food, the weather, and everything around you is completely different, and often your body needs time to adjust – even if it means living in complete discomfort for several days.

Guess what… it’s possible to live without technology for a month!

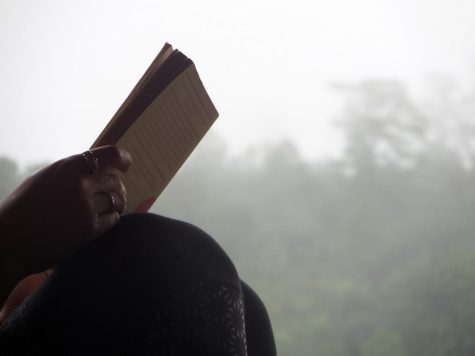

Taking time out of our busy day to read and journal.

Taking a break from technology for a month was a liberating experience. My unhealthy habit of constantly checking my pocket when I felt a phantom buzz pretty much disappeared. To be honest, part of me didn’t want to get my phone back. Living phone-free made me realize how much I relied on my phone as a way to pass time and avoid small talk. During the course of the month, when waiting for a train or food at a restaurant, my friends and I would discuss politics and share stories instead of hiding away behind a screen. To record my experiences, I journaled daily, and I found joy in taking the time to write out my feelings rather than mindlessly typing away at a screen. The internet cafes, which I used once or twice a week to update my parents and friends, made me appreciate the luxury instant messaging. I even took up reading as a hobby, and looked forward to the “silent hour” before bed every day to dive further into my book.

I think what made it much easier for me, at least partly, was having a group of friends and mentors who were also living tech-free. Instead of turning to a device for entertainment, we turned to ourselves and made memories we otherwise wouldn’t have made if we were consumed by our phones. On the plane ride back to Japan, I thought about how I was going to apply these vital lessons I had learned in Thailand at home. Living in a technology-consumed society, I knew I was eventually going to go back to using my phone, but I set some rules for myself to limit my technology usage. I promised myself to continue reading, at least a little bit each day.

Flying over rural Thailand on the way back home.

Living in a world completely different from your own is one of the best ways to broaden your mind and develop the skills necessary to tackle the many unpredictabilities of our world. The lessons I learned in Thailand ignited a desire within me to keep travelling and to continue to work on becoming a better global citizen.