Peace knows no borders

I have always felt a part of my heart wrench when hearing about any bombing, including that of Hiroshima. However, as a Korean, I have to admit that the particular date August 6, 1945 also rings a celebratory bell of Korean Independence. To me, and many other Koreans, this day was when our country was freed after three ugly decades of Japanese colonial rule, and this fact remains true and will throughout history. Still, in retrospect, I realize that this sentiment of nationalistic celebration may have been casting a shadow over humanistic sympathy. I didn’t know that these two seemingly conflicting emotions could coexist in one’s heart until I traveled to Hiroshima this October with my senior class.

I remember walking into the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and seeing the first photograph in the exhibit. It was a black-and-white photo of the bombing, a typical image of the atomic mushroom cloud. This was not surprising as we have all seen this picture too many times in textbooks. Never having been one to cry in public, I braced myself to keep my casual bravado — after all, I “knew” about everything I was about to see in this room from my history textbooks. How arrogant I was to boldly assume that I could dare “know” the depths of the victims’ despair, the dejection of having one’s life snatched away in a mere second, the sorrow of seeing one’s ten-year-old sister plea for even a drop of poisonous water to alleviate the burning thirst in her tender throat. Now I see how blinded I had been.

Room after room was filled with victims’ first-hand and second-hand testimonies of the tragedies following the bombing. In one corner was a half-torn, ash-covered uniform half the size of myself with a rectangular name tag on its chest also ash-covered, the letters barely recognizable as letters if not shapes. Apparently, it had belonged to a middle-school boy who had gone to work at a city construction with his school friends. The morning he left his home that day was the last time he said goodbye to his parents, who later found their son’s dead body floating among the many other dead boys in the river. The boys looked like floating “radishes”, the plaque next to the uniform explained — how terrible it must have been to compare middle-school boys to “radishes”.

The saddest of all, however, was how everyone died within the three to four months period since the bombing in August. Soon after the event itself, those who miraculously survived the initial bombing were to be tested again with the excruciating pain of burns, bleeding gums, falling hair, purple spots, high fevers, and then again with the long-term effects such as cancer. Hopes of returning to their peaceful lives were given up home after home, family after family, as each of these souls who had shared a moment of relief for surviving the bomb began to manifest symptoms of radiation poisoning after weeks or months. Just like the first wave of deaths, when mothers could do nothing but watch their children beg for water as they slowly died, there was nothing people could do to save their loved ones in this round of deaths. The impotence of these friends and family as they watched their loved ones slowly reach death was what took the final toll on Hiroshima’s lasting tragedy.

In the exhibit were many others weeping for these victims, and I was among the many foreigners in the room, glasses all fogged up from tears. And I still remember the shared air of solemnity in the tourist-packed room. Regardless of age, gender, or race, we were bound by the very human sense of empathy from the deepest part of our hearts. And this, I learned, is why the museum is named the way it is: the Peace Memorial.

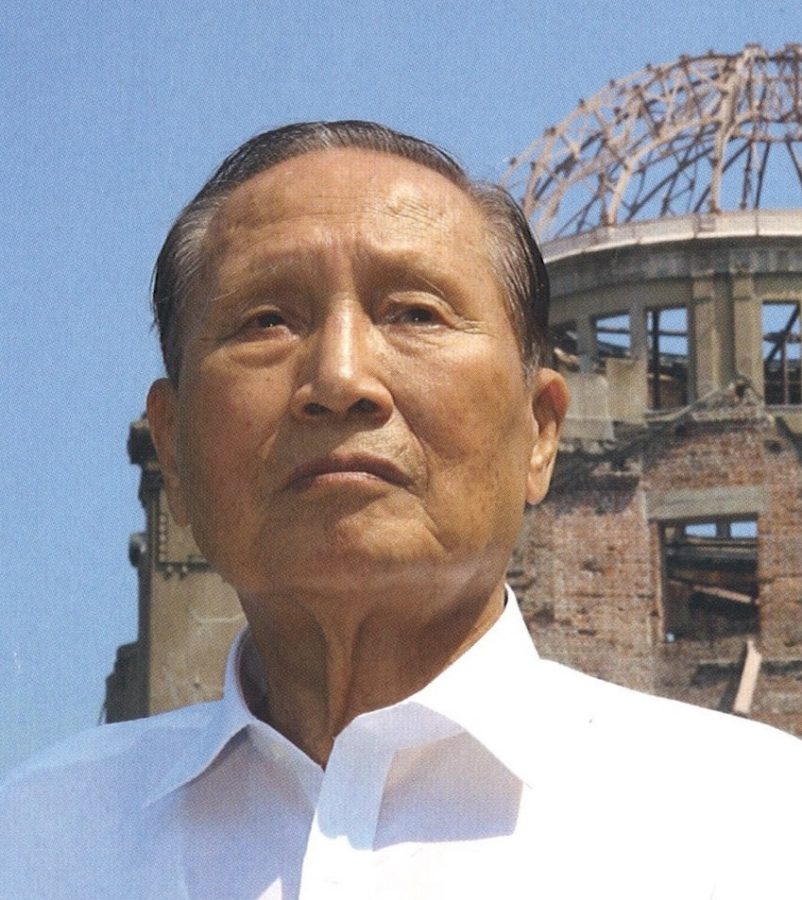

Kwak was one of the Koreans who was conscripted to work in Hiroshima during the Japanese occupation of Korea.

Amidst my teary glasses, I saw a Korean name on one of the plaques describing another victim. It was about a man named Kwak Kwi-Hoon, a survivor of the bomb who had been conscripted to a unit in Hiroshima from Jeonju, Korea, a year prior to the bombing. As the plaque read, he was bombed “at roughly 2,000 m from the hypocenter while on [his] duty” and fell into a coma for several days after suffering from severe burns. What was most astonishing, however, was not that he survived his injuries from the bombing but his actions afterwards. After the end of World War II, Kwak was able to return home to Korea, where he settled as a teacher and dedicated himself to supporting other A-bomb victims. In 1967, he founded the A-Bomb Sufferers Association in South Korea as a means to demand adequate compensation for them from the Japanese government. His slogan for this campaign was “A-bomb survivors know no borders.” Knowing this, I couldn’t help but feel ashamed of myself for my previous nonchalance, looking at the atomic mushroom.

Kwak has devoted the rest of his life since 1945 to send this message to the rest of the world and the Japanese government — that peace was not to be divided by borders but to be universal. I later read in The Chugoku Shimbun that he finally won his lawsuit against the Japanese government in 2002, after many failed attempts, to amend Directive No. 402, a provision that prohibited foreigners from receiving a health management allowance from the Health and Welfare Ministry after leaving Japan. Although the Japanese government has claimed that the result of this court case “would not appeal”, A-bomb survivors in the United States and Brazil have been given access to relief measures thanks to Kwak’s victory.

Kwak is certainly not the only survivor who seeks to spread the message of peace globally. Many others travel around the world to let people know of the humanity that is often times hidden behind the texts and images in history textbooks. At the end of the day, their stories are the stories of humans and their struggle to forge on with the scars of the past on their backs.

The violent images of war, bombs, fire, and corpses in Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial come together to remind our benumbed selves the scars we are capable of inflicting on each other, the ability to heal, and the importance of remembering these lessons; peace was the result of this awareness. We, having witnessed destruction before our eyes, bowed our heads to the hibakushas (atomic bomb survivors), sincerely sorry for the pain the victims had to go through.

While nuclear weapons will remain contentious in political discussions, we must always remember that there will always be individuals who have to live, and suffer, the consequences of a political decision. And there is nothing political about people’s scars.