New guidelines to the Olympic Charter begin a new phase to the long hostile relationship between Olympics and politics

Creative Commons

Tokyo 2020 sign in Ariake, Tokyo. The Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics, which was held from July to August 2021, gained international attention for athlete expression on the field.

The Black Lives Matter movement, expedited in response to the wrongful and fatal treatment of George Floyd, gained international attention even amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. According to The Atlantic, Black Lives Matter demonstrations took place in multiple countries including Japan, Australia, Brazil, Spain, Senegal, Germany, between June 5 to 6, 2020. The social media movement #BlackoutTuesday, also initiated in response to the death of George Floyd and the persistent discrimination against the black population, gained innumerable participants. The Guardian reported that participants of this movement not only included regular social media users, but also celebrities like Ariana Grande and Dwayne Johnson, social media powerhouses like TikTok, and museums like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Queens Museum in New York.

One of the boosters for this change was how vocal many athletes chose to be towards these social problems after returning to competitions from their pandemic hiatus. The 2020 US Open champion Naomi Osaka wore the names of Black victims of alleged police violence or racist hate crimes on her mask every match, one name per day, attracting attention internationally.

In the series of photographs published by the CNN in 2020, Tyler Wright, the two-time World Surf League champion; Cameron Champ, a professional golfer; Bubba Wallace, a race car driver for NASCAR; and many other athletes from the US and beyond are shown expressing their support for the Black community and calling for an end to racism.

Individual athletes were not the only ones to react. Popular sports leagues in the US voiced their protests along with their athletes’. In late August 2020, the NBA, MLB, NHL, and WNBA postponed their scheduled games following the Milwawkee Bucks’s boycott of their NBA playoff with Orlando Magic. The boycott was in response to the police violence against Jacob Blake, a Black man who was paralysed from waist down after being shot seven times in the back in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

With a very large portion of the sports world voicing their protests on the field, it was only natural that people expected the same—or even more—from Tokyo 2020.

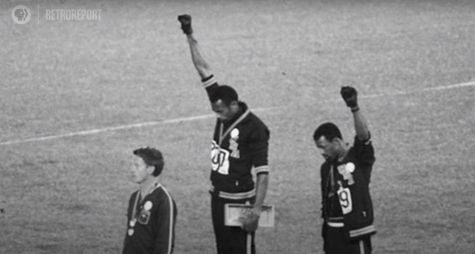

However, the Olympics and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) have had a long history of intolerance towards politicisation of the games. With strict restrictions on the voicing of opinions by athletes on the field, the IOC had basically prohibited any charged expression. It is explicitly written in Rule 50.2 of the Olympic Charter (as of November 2021) that “[n]o kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.” A famous violation of this policy took place in Mexico City 1968, when American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists on the medal podium after receiving a gold and bronze medal respectively.

Their gesture, sometimes regarded as the Black Power Salute, breached the predecessor of the current Rule 50, which stated that “[e]very kind of demonstration or propaganda, whether political, religious or racial, in the Olympic areas is forbidden.” The two Olympians faced severe consequences for their action: they were removed from the team and returned back to the US, and became personae non gratae in the Olympics community for multiple decades.

On October 27, 2020, Thomas Bach, an Olympic gold medalist and the current President of the IOC, released a statement on the IOC’s official website. Asserting that “[t]he Olympic Games are not about politics”, Bach described his experiences surrounding two particular Olympic games in the statement: first as an Olympian at Montreal 1976, when several African athletes were forced to leave after their governments’ decisions to boycott the games, and second as the chair of the West German athletes’ commission at the time of Moscow 1980, when his objection to West Germany’s boycott of the game ended in vain. He commented that the African athletes’ “devastation of having their Olympic dream shattered at the last possible moment after so many years of hard work and anticipation still haunts [him] today” and that the experience of not being heard by politicians in the West German boycott of Moscow 1980 was “a very humiliating experience.”

However, this policy has faced criticism in recent years. According to an article from the LA Times published this July, the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee released a statement in 2020, denouncing Rule 50 as a “[violation to] athletes’ rights to free speech and freedom of expression.” In the same article, Tommie Smith stated that he “[thinks] the athletes have a right to say whatever is on their mind, whether it’s agreeable to those who are watching or it’s thought of negatively.” Later that month, he joined John Carlos and over 150 other athletes, educators, and activists in signing a letter addressed to the IOC, requesting not to make athlete demonstrations a subject of punishment.

On July 2, the IOC implemented a set of guidelines regarding Rule 50.2 of the Olympic Charter, specifying the times in which athletes were allowed to “express their views” during the games. A notable point of this new guideline was that it included “the field of play prior to the start of the competition” as a place where athlete expressions were acceptable. This modification in the rules allowed the British women’s soccer team to take a knee as a sign of protest against racism and discrimination on the first day of competition, before the start of their game against Chile.

The Chilean team quickly followed the British team’s gesture, and the women’s soccer teams from Sweden, the US, and New Zealand, who also competed that day, took a knee as well before the start of their game. The referee and the assistant referee protested together with the athletes before the match between the US and Sweden.

Some criticised this alteration to the rule as just a publicity show, and they may have been accurate to an extent. On July 21, The Guardian reported that the Tokyo 2020 official social media crew were prohibited from publishing photographs of athletes taking the knee or protesting in any other way during the games. A few days after this story became public, the IOC made an abrupt change in policy and tweeted a picture of Lucy Bronze, a British soccer player, taking a knee before a match against Chile.

The IOC’s relaxation of their policies have brought positive changes. Yet, controversies remain for how much expression should be allowed for the athletes.

In early August, US shot putter and silver medalist Raven Saunders became subject to an investigation by the IOC for a gesture she made on the medal podium. Saunders, who is black, lesbian, and has battled mental health issues, crossed her arms above her head making an “X” symbol, signifying “the intersection of where all people who are oppressed meet.” The medal podium was not specified as a place where athlete expression was acceptable in the new guidelines published by the IOC prior to the games, while Reuters reported that the US Olympics and Paralympics Committee (USOPC) concluded that it was not an infringement. This investigation was suspended in response to the death of Saunders’s mother, who passed away two days after the medal ceremony.

Just a day after Saunders stood on the medal podium, Chinese gold medalists for track cycling women’s team sprint came under public attention for wearing pin badges with the profile of Mao Zedong at the medal ceremony. After requesting and receiving an explanation from the Chinese Olympic Committee for an explanation over this matter, the IOC put a closure to it by issuing a warning to these athletes.

Beijing 2022 will start in February next year. It will be interesting to observe how this trend in athlete expression will continue, and how it will be received in Beijing and the rest of the world.