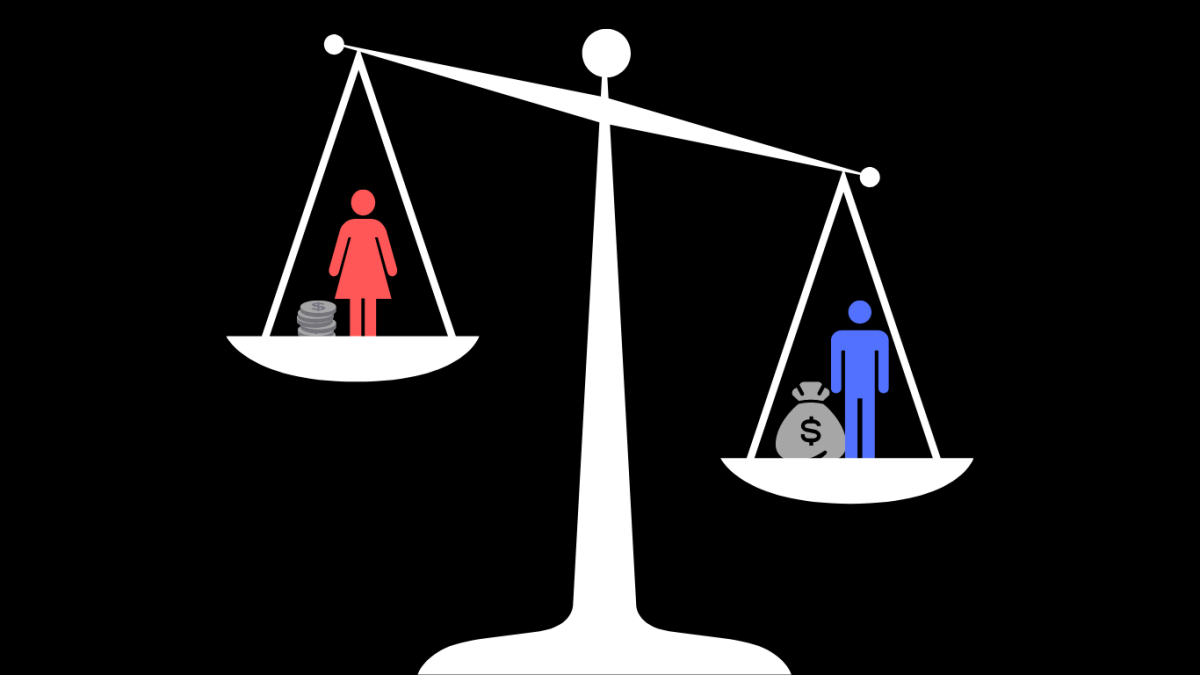

Women-only train cars sidestep the root issue of gender inequality

Garam, Wikimedia Commons

Women-only train cars in Japan have been operating for over a century. Pictured above: The platform of a women-only train car at JR Namba station in Osaka.

Chikan (痴漢).

The Japanese term for sexual harassment or molestation, chikan is a word all too familiar to the vocabulary of young girls and women in Japan. As the word began to make its way into the international lexicon, conversations on the problem of groping on Japanese public transportation were reignited. Although instances of molestation are not limited to Japan, its number of cases continue to overshadow other developed countries: foreign governments such as the UK and Canada warn travelers about the prevalence of chikan on Japanese metro systems. The Japanese government and railway companies have attempted to acknowledge this problem by adopting women-only train cars. However, their initiatives have been unable to make significant progress. Why have their efforts been unsuccessful, and why does this issue persist to this day?

In 1912, Women-only train cars were introduced by the Tokyo Chuō line as “hana densha” or flower cars. Following WWII, an increasing number of railway companies adopted this practice to protect women and children from rush-hour traffic and crowded trains.

In 1973, women-only train cars were replaced by priority seats, which are reserved for the elderly, people with disabilities, pregnant people and people accompanied by small children. It was not until 2000 that increasing reports of sexual harassment on trains in Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya lead the police department to recommend train companies to introduce preventive measures. After a record 2,201 chikan cases were reported in 2004, many railway companies began to operate women-only train cars during rush-hours (7:30 to 9:30) on weekdays.

In the last two decades, women-only train carriages have had positive effects on the experience of women on public transportation. According to a survey conducted by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, 70% of women who use public transportation in Japan are in favor of women-only train cars. Although safety is still their top concern on transport, most of them no longer fear sexual harassment when boarding trains. Having a women-only space on public transportation can help provide women with “peace of mind” said a spokeswoman from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

Others were less supportive of women-only train cars, making public statements of objection against the necessity and justification of its implementation. In 2017, all five committees of the Nagoya City Council received packages of a foul-smelling yellow liquid from an unidentified individual. This package included a message demanding the politicians to intervene in ending the use of women-only carriages on the local Higashiyama subway line.

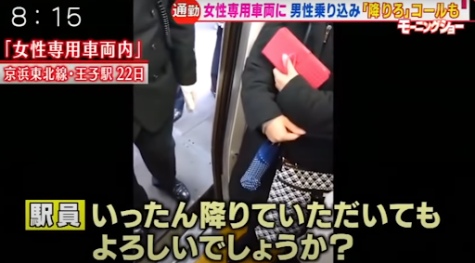

Some men have staged individual protests by boarding women-only carriages and refusing to get off, even when confronted by other passengers and station attendants. These protesters often refused to recognize the train cars as being reserved for women, repeating that “Ima dake onna” (just for now, I’m a woman as well). Others pressed the station’s emergency button after claiming that they had been attacked to stop the train’s operation. Some female passengers directly confronted the men, expressing their anger and stating that they feared for their safety.

An overwhelming majority of criticism towards women-only train cars stem from the fears of Japanese men who feel threatened by the increasing influence presented to women. By empowering women, women-only train cars marked a change in the long-lasting pattern of gender/sex-based power imbalances in Japan. According to the World Economic Forum’s 2021 Global Gender Gap Report, Japan placed 120th out of 156 countries for gender equality with an overall score of 0.66. The overwhelming reason behind Japan’s ranking is the lack of empowerment and leadership opportunities made available to women. Both the economic and political fields lack sufficient female representation in positions of power. For example, only 3 out of 20 members of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s cabinet are women. As a result, most Japanese men have been able to exert considerable power and domination over Japanese women.

Author and mental health/welfare professional Akiyoshi Saito claims that the desire to exercise this power is the primary motive behind molestation on public transportation. In his book, “Otoko ga chikan ni naru riyu”(The reason men become chikan), Saito argues that chikan has little do with sexual desire, but is rather a consequence of internalized misogyny and a desire for female subjugation. He explains that many perpetrators believe that sexual assault can be justified based on a system of male superiority. Therefore, by empowering more victims to speak out against their molesters, women-only train cars have limited and threatened the control Japanese men are able to exercise over women.

Negative criticism toward women-only train carriages has also been broadly televised in the media. On January 13, 2020, the “Hatori Shinichi Morning Show” of TV Asahi aired a feature on the negative behavior of passengers on women-only train cars. Reporters interviewed women who allegedly refrained from riding women-only cars because of the high tension and conflict the environment creates. “Women are pushy,” said one interviewee. “When men aren’t around, they don’t care whether people can see them.” Another responded, “Women who have the same branded products compete to see who has the newest one, it’s a contest to be on top.”

Five days later, the television show “Gutto Luck” from TBS aired a similar program titled, “Why on earth are there women who don’t want to ride the women-only cars?” which explored similar testimonials from women who were against using women-only carriages. One of the show’s hosts, Tatekawa Shiraku said, “If there were men, they’d be more self-conscious, and quit that (bad-mannered behavior) wouldn’t they? They should come up with regulations (on women-only cars).”

Women-only train cars were created as a solution to empower women against patriarchal discrimination and combat gender inequality in Japanese society. Yet why does its implementation seem to have only encouraged misogynistic perceptions and behavior?

One reason for the ineffectiveness of women-only train cars lies in a popular male perception that groping is not a problem that deserves to be treated seriously. “It is rooted in the perceptions of a long-standing male-dominated society which has accepted groping and treated victimhood of groping lightly,” said Masako Makino, doctoral researcher and author of “What is chikan? A sociological study of harm and false accusations.” When molestation is not treated as a serious crime, the premise for the existence of women-only train cars is weakened. Some social media trolls have even suggested the creation of “molestation cars”, as a “win-win situation for men who want to molest and women who want to be molested.”

A lack of acknowledgment of the gravity of sexual harassment means that many victims are accused of making false claims. Some women have taken to social media to protest the lack of public support for victims of molestation. “Women cry themselves to sleep, because they know that even if they’re actually molested and shout that someone molested them, the responses would be: ‘You’re trying to socially kill me with false accusations’,” said one Japanese woman on Twitter. “Not only do they cry themselves to sleep, they also become the target of hatred. The blame is put not on molesters or the judicial system, but on women. It must be a paradise for molesters.”

This perception has also created a culture of victim-blaming. In 2019, an anti-groping poster created by the Japanese school uniform manufacturing company Kanko generated criticism for targeting female victims rather than male perpetrators. “The short skirt that you think is kawaii leads to sex crimes,” the poster read. “And it’s not just you, but your friends and companions too.” Although the statement was quickly retracted, this demonstrates how Japanese society tends to place the blame of molestation on innocent victims for dressing too provocatively or attracting attention.

Women-only train cars do not present a sufficient solution to the prevalence of groping. Rather, there are many underlying issues that exist beyond molestation that are preventing such a permanent solution. As a result, it is necessary to begin taking a different approach by focusing on raising awareness about the issue rather than avoiding it. For example, the Molester Deterrence Activity Center activist organization hosts an annual design contest to create anti-chikan badges. To direct awareness towards perpetrators and bystanders on the extremity of the issue, these pins make statements such as “Groping is a crime” and “We won’t take this quietly.”

But the most important thing to realize is that the problem of chikan is not a burden for women to carry alone. In response to a Twitter post that promoted victim-blaming culture in molestation cases, one user wrote, “’Chikan’ aren’t just a threat to women, they’re a menace to society as a whole.” The elimination of chikan as a threat to the safety of both male and female train passengers cannot be achieved without the cooperation of the entire public.

By promoting awareness of the gravity of chikan, we can encourage more victims to speak up against molestation.