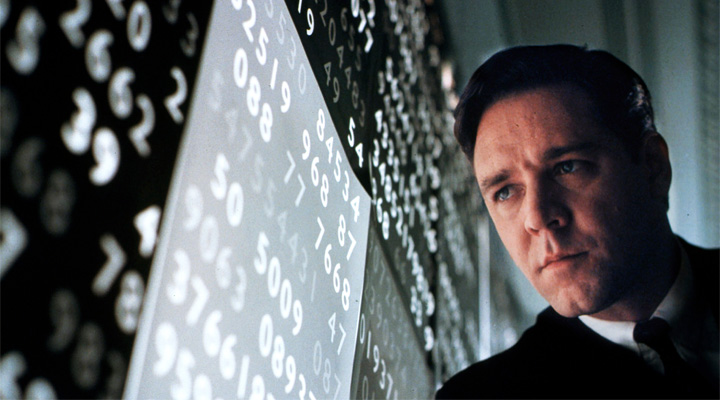

(Gage Skidmore)

“We will defund sanctuary cities once and for all. No more safe havens in America,” said Nikki Haley, United States presidential candidate. “We’ll go back to the Remain in Mexico policy so that no one even steps foot on US soil.” Despite being born to immigrant Punjabi Sikh parents from India, one of the core principles of Haley’s 2024 presidential campaign was enacting stern immigration laws rooted in deportation, even marketing the catchphrase “Catch and Deport” as opposed to the traditional “Catch and Release.”

“Stop the Boats,” said Rishi Sunak, British Prime Minister (2022-2024), enacting a 2024 policy to “stop the boats” of illegal immigrants into the UK and send asylum seekers to Rwanda. Despite being born to East-African-born Hindu parents, Sunak implemented the UK’s toughest illegal immigration rules with the goal of ending the “legal merry-go-round” and stopping people from being able to “exploit [the UK’s] legal system” with “spurious claims.”

Both Haley and Sunak, along with dozens of other notable international politicians, share both their sentiments to limit mass immigration as well as their immigrant backgrounds.

“They benefited from this, so shouldn’t they want that for other people too?” has been a question recently asked not only to politicians, but also to the growing number of children of immigrants who take firm stances against immigration. As anti-immigration policies and rhetoric continue to spread globally, a pressing question emerges: why are some children of immigrants so strongly opposed to it?

For many children of immigrants whose families have been long-established in their communities, it feels as though recently arriving mass migrants are receiving (or even “stealing”) greater benefits without having to encounter the same challenges or necessary hard work. Increasingly, children of immigrants view their nation’s priorities unfairly shifting towards newly arriving migrants, leaving pre-existing immigrant communities feeling overlooked and overshadowed.

One of the most prevalent issues that has evoked widespread anti-immigration narratives is the strain on a country’s resources. In many G12 countries (a group of twelve advanced international economies including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and others), housing prices have skyrocketed even as the labor force has declined. Citizens of G12 countries note the dire effects of the situation, noting that their countries’ infrastructure haven’t grown in tandem with the number of migrants they’ve received. A group of Canadians interviewed by The Guardian expressed their frustration, stating that Canada “should’ve also done the hard work,” figuring out logistics like housing and income for migrants before allowing them to enter the nation.

Second-generation immigrants, who often live in the same communities as newly arriving immigrants, tend to feel the effects of overcrowded housing markets and limited resources to an even greater extent. Newly arriving immigrants often settle in communities with pre-existing immigrant populations, creating a heightened competition for schools, jobs, resources, and affordable housing. For many children of immigrants who were born in a certain country or have spent the majority of their lives in one place, this pressure evokes a stronger sense of belonging and a greater claim to resources.

In 2024, a wave of Nicaraguan asylum-seekers moved to Whitewater, Wisconsin, United States. According to PBS Wisconsin, many of the Nicaraguans had found housing in the neighborhood, sent their children to the town’s public schools, and got the same factory and food-processing jobs as long-established immigrants and immigrant children. “It’s not fair,” said Rosa, a Whitewater resident who immigrated to the United States over 30 years ago. “Those of us who have been here for years get nothing.” Rosa’s sons voted to end mass migration, describing benefits like work permits and drivers’ licenses immediately available to immigrants.

ProPublica interviewed dozens of long-established Latino immigrants and their U.S.-born relatives in the American cities of Denver and Chicago and found strong feelings of resentment. They spoke of their dissatisfaction as they watched the government give newly arriving asylum-seekers immediate access to work permits and IDs, and in some cities, spending millions of dollars to provide them with food and shelter. A friend of Rosa’s, Valadez, describes the injustice of the benefits received by the Whitewater asylum-seekers. “I have been here for 21 years,” she said. “I have five children who are U.S. citizens. And I can’t get a work permit or a driver’s license.”

The growing feeling of resentment against newly arriving migrants has extended beyond just children of immigrants, but also to larger communities across nations. Anti-immigration sentiment has risen across the globe. In the United States in 2023, state legislatures saw 132 anti-immigrant proposals, a whopping 106% rise from the previous year. This sentiment, although sparked by waves of recent mass migration, has been targeted towards all immigrant groups—even long-established children of immigrants. A common feeling expressed by second-generation immigrants was the reopening of problems by new waves of immigrants. Second-generation immigrants felt as though their parents and their families had worked hard to overcome racism and prejudice to integrate into society, only for progress to be undone by the issues brought by new migrants. Gustavo Garagorry, president of the

Venezuelan American Republican Club of Miami-Dade, stated in an interview for NPR that he believed that half or more of newly arriving immigrants from Venezuela, his home country, were “criminals.” Garagorry worriedly stated, “we don’t want them here […] it’s not good for the reputation of the Venezuelan people.”

Mass migration has become a widely discussed topic in the media, often described as “ruining countries” and “displacing citizens,” but how accurate are these claims? Politicians and journalists have often framed immigration in a negative light, with some, like New York City Mayor Eric Adams, gravely warning that an influx of migrants “will destroy” the city. Anti-immigration rhetoric, like

that expressed by Adams, has become increasingly prominent and dramatized, often used to foster divisions among immigrant communities for political agendas. However, while the consequences of immigration have often been given the spotlight, the positive aspects have largely remained in the shadows. For example, Boston University economist Tarek Hassan demonstrates that immigration actually boosts local businesses, new patents for innovations, and overall “raises the wages of the people who are already there.” Immigration has also become the saving grace of many developed nations suffering from demographic crises. Overall, Pia Orrenius of the George W. Bush Institute argues that the overall benefits of immigration largely outweigh the costs.

The rise in anti-immigration sentiment among children of immigrants may seem contradictory to some, but it is important to recognize that communities are diverse and individuals hold a wide range of views. While some children of immigrants may share a common background, second-generation immigrants, like all people, hold diverse perspectives shaped by differing personal experiences, lives, and environments. Each person’s view is complex and cannot be spoken for by just one singular belief or reduced to just one singular viewpoint.