Japan’s population is 123 million today, but it could be 100 million in just 25 years.

2025 marked the 14th consecutive year in which Japan’s population declined, maintaining an average decrease of half a million people per year. With a birth rate of just 1.3—a number far below the level needed to maintain a stable population—the nation faces a serious demographic crisis.

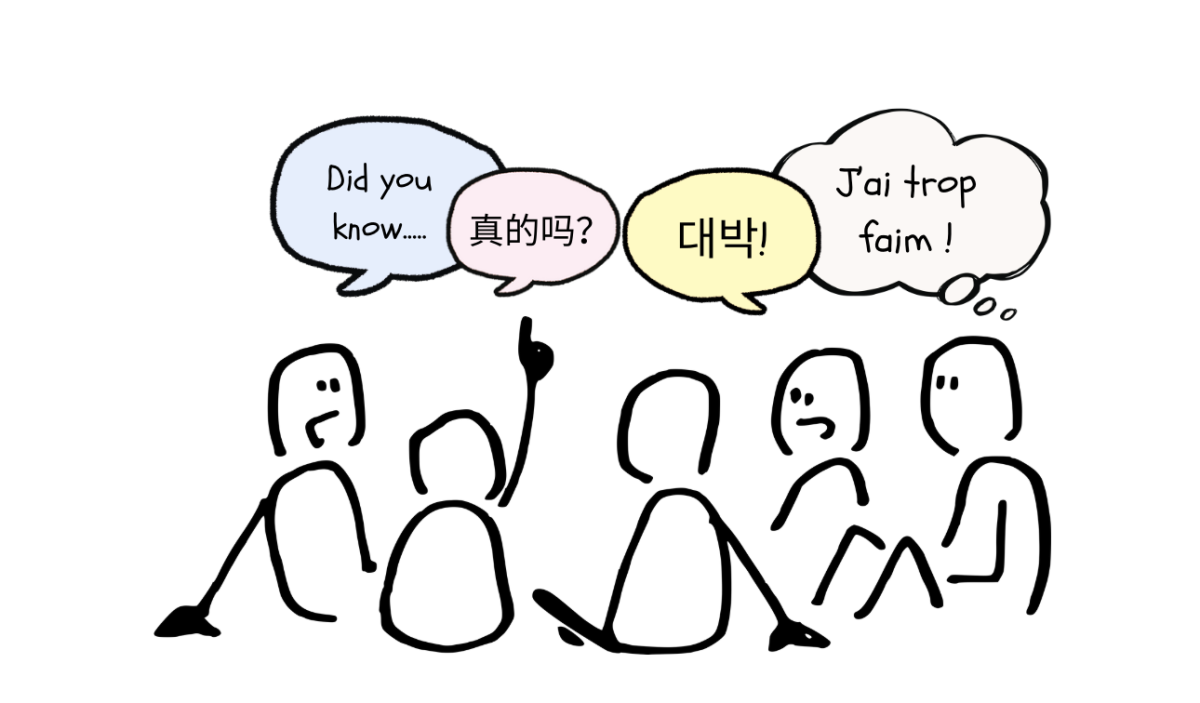

However, this crisis is more than just a distant issue for economists or the Japanese government. It is an issue that raises important questions about the future of work, education, career, family, and national identity. Yet, alongside these challenges lies a significant opportunity: foreign workers could greatly change the future of Japan’s labor force. As the country struggles to address its aging population, welcoming a more diverse workforce could prove to be a solution, one that not only addresses labor shortages but also introduces new skills.

The reason for Japan’s long-standing population decline is due to a socioeconomic unhappiness that has driven a new generation of young Japanese citizens to postpone love, marriage, and childbirth in order to make ends meet. A stark example is karoshi, or death by overwork. Japan’s work culture has long been notorious for its demanding schedule and extensive overtime. According to JapanDev, the average monthly overtime for a worker is 24.3 hours—an almost 13-hour difference between the average 11.6 hour monthly overtime in the United States. Because of the extreme responsibility a job in Japan entails, many Japanese employees find it extremely difficult to manage a healthy work-life balance, rarely maintaining enough time for a personal life. Within Japanese work culture, it has become increasingly normalized to relinquish social events and personal commitments in exchange for corporate life.

However, despite the demanding hours and sacrifices made by Japanese workers, they still find themselves unable to support themselves comfortably. Living costs in Japan continue to rise as taxes and inflation drive prices up enormously, yet salaries and job opportunities steadily fall. In a nation where starting a family seems more like a burden than a benefit, people are leaving their ideas of family behind.

Beyond economic pressures and work culture, ever-changing social norms also continue to reshape how young Japanese people view marriage and family life. As Japanese workers spend more time in their workplaces, careers and individual goals have become far more emphasized in society in place of traditional values like marriage, especially for women. Traditionally, Japanese women were expected to leave the workplace behind after marriage and childbirth, but as more women pursue careers and achieve success, many have become reluctant to step away from their jobs. More Japanese women are going to college, more Japanese women are going to work after graduation, and more Japanese women are no longer seeing solely marriage as the road to happiness.

These economic and cultural shifts impact more than just individual lifestyles—they risk Japan’s livelihood as an entire nation. As fewer young people decide to pursue families, whether due to economic hardship, stress, or evolving societal norms, the entire country faces a rapidly declining labor force.

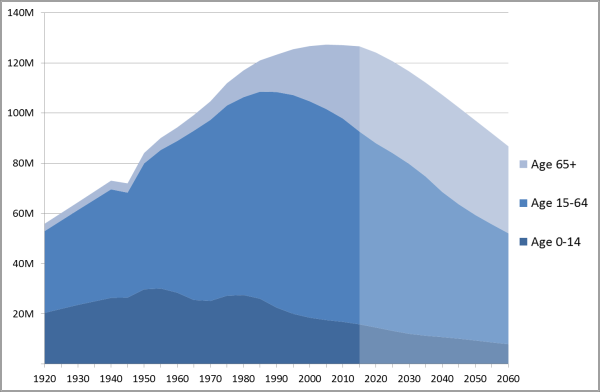

The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research states that the working-age population from the ages of 15 to 64 decreased by 15% between 1995 and 2023—a number that will surely continue to go down without a feasible solution. As Japan’s labor force continues to decline, it is projected that by 2040, the country will lack over 11 million workers.

Due to the rapidly declining number of youth and the subsequent shrinking of the labor force, Japan has seen an increasing scarcity of key jobs in healthcare, construction, and manufacturing, especially. These sectors face the most intense labor shortages in the nation, with construction workers even grappling with a jobs-to-applicants ratio of 5.60, meaning that there are about 5.6 job openings for every one person applying. While the labor shortages of certain industries are the most pressing, Japan as a whole is experiencing the lowest labor productivity of all G7 countries, producing the lowest number of GDP from national workers in comparison to Canada, Germany, the United States, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Evident with Japan’s 2024 loss as the third-largest economy to Germany, the country’s national income is seeing a monumental decline.

Further adding to the challenges, while Japan’s working-age population and thus national income shrinks, the number of elderly who receive pension payments is increasing at a faster rate than ever, increasingly pressuring the nation’s labor market and social security system. Japan spends an estimated 16% of its national income on social security—an absolutely enormous number compared to other G7 nations like the United States, which spends only around 5%. While 16% is already an exceptionally large number, that figure is only projected to rise continuously as the number of elderly people to support grows, but the number of people making money to support them shrinks.

With the labor force shrinking and the need for social security increasing, discussions have been held on whether to extend the senior retirement threshold. According to the World Economic Forum, surveys indicate that approximately 80% of Japanese workers would want to continue working after retirement. Nevertheless, the current age of retirement for the majority of Japanese corporations is 65, and there are still significant barriers to senior employment. It is regulated by Japanese law that once a person reaches the age of 60 and their combined salary and pension exceed a certain amount, their pensions are reduced. Whilst senior employment is on the rise, this significant obstacle inhibits many senior citizens from remaining in the workforce after their retirement.

To combat the issue of a declining workforce, Japan can no longer solely rely on its own citizens. Thus, immigration is considered a key solution to compensate for Japan’s rapidly declining workforce. According to the Asahi Shimbun, the number of foreign workers in Japan with a “Specified Skilled Worker” visa has sharply increased, with the numbers rising to approximately 250,000 people. Skilled foreign workers are foreigners who are designated with the specific skills and knowledge to be able to work in a certain field or industry. The “Specified Skilled Worker” visa grants residency status to these immigrants, which provides support as well as secure employment. As pandemic restrictions eased in the spring of 2022, the number of people applying for this worker visa has increased substantially, and is projected to increase even further.

Another potential solution regarding labor shortages in Japan is through the development of technology. In industrial sectors of transportation, agriculture, and construction — all of which are significantly impacted by Japan’s rapidly aging population — the government is investing heavily in technologies that will support the aging workforce and perhaps gradually work towards substituting human labor.

A notable example is within the Japanese agricultural industry, which is currently deemed the industry with the most potential for innovation. In 2022, 70 percent of farmers were above age sixty-five. To combat the issue of an aging farming population, the Japanese government is actively promoting the use of IT in farming. Also dubbed as the “Smart Agriculture Project,” the program aims to increase the automation of tasks through robotic tractors, drones, and the use of AI tools for data gathering and optimization of crop growth. This would enable inexperienced personnel to operate agricultural processes, greatly contributing to the farming industry.

Again, the Japanese technological sector could also benefit immensely from the rising number of immigrants and skilled foreign workers who are acquiring visas to work in Japan. By industry, currently 590,000 foreign workers are employed in Japan’s manufacturing and technology sectors, accounting for 26% of the country’s 2.3 million foreign workers. The increase in the number of specialized workers helps fill these labor shortages, which, in return, allows foreign workers to gain access to career opportunities.

Hiroko Akiyama, a professor at the University of Tokyo’s Institute of Gerontology, claims that “aging societies have the potential for innovation.” While the concept of an aging society may initially seem demoralizing, it essentially opens the door to numerous new possibilities. The Japanese government is expected to continue investing in technological development, while the demand for foreign skilled workers in these sectors is only expected to grow. In this way, Japan’s population crisis holds significant potential—both for innovation and diversifying Japan’s labor force.