Why people are boycotting Russian culture

Photo credit: Efrem Lukatsky

A Ukrainian soldier standing in front of an apartment ruined by Russian attack.

May 19, 2022

On February 24, Russian President Vladimir Putin launched a large-scale military invasion of Ukraine. While the conflict between Russia and Ukraine has been an ongoing event since 2014, when the Ukrainian Revolution took place, the current army attack is the biggest war in Europe since World War Two. In his address speech, Vladimir Putin claims that the reason for the invasion of Ukraine was to “demilitarize and de-Nazify Ukraine” and to “bring to trial those who perpetrated numerous bloody crimes against civilians.” However, putting the long history behind Russia and Ukraine relations into consideration, many believe that the actual reason is to prevent Ukraine from joining NATO and asserting its dominance over Ukraine.

According to statistics by Reuters, the first three months of the war resulted in severe damage in both nations, causing at least 46,000 deaths, 12,000 injured, and 13 million displaced in total. The economic losses were also devastating, not only to both Ukraine and Russia but also to the world economy since Russia holds great power as a global gas supplier.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has received a significant amount of criticism from the rest of the world. In the NATO leaders meeting in Brussel on the 24th of March, the leader of 30 member states agreed to “continue to impose unprecedented costs on Russia, and … reinforce Allied deterrence and defense.” The European Union also announced several sanctions regarding trade with Russia.

Currently, almost 1,000 companies have publically withdrawn their business from Russia. This includes some major brands, such as The Walt Disney Company and Netflix in media, Adidas, Uniqlo, and Ikea in consumer goods, Mcdonald’s and Starbucks in food, and Mastercard and Visa in finance. By pulling out of Russia, companies can publicize their opinion toward the Russian invasion of Ukraine and earn support from the consumers that stand with Ukraine. In a report by DW, Tatiana Mikhailova, an economist and lecturer at the New Economics School in Moscow, states that departing corporations had an enormous impact on Russian citizens and its economy, resulting in increased unemployment and negative effects on all sectors of the Russian economy that use foreign components.

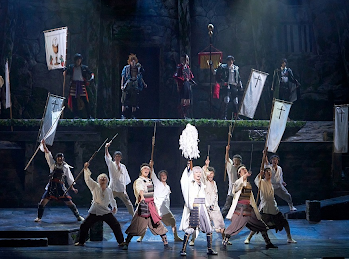

Actions against the Russian invasion also expanded its effect on culture. The cultural boycott of Russia started as important cultural figures and corporations began to show their support for the Ukrainians by closing ongoing exhibitions in Russia or refusing to collaborate with Russian artists. Ukrainian Institute, an organization that works to strengthen Ukraine’s international standing, strongly claimed that Russian culture is part of their political agenda, which is why people should suspend any cultural cooperation with Russia until it completely withdraws from Ukraine. One method of cultural boycott suggested by the Ukrainian Institute on their website is to “cancel any cooperation with Russian artists, no matter how great or famous, as long as they openly support Putin’s regime, silence its crimes, or do not publicly and directly oppose it.”

Individuals, primarily Ukrainian artists working in the cultural field, also spoke openly about the boycott movement. In an open letter, Oleg Sentsov, a prominent filmmaker from Ukraine, strongly argued for the boycott of Russian movies by signing the Ukrainian Film Academy’s online petition. In an article by Variety, Nariman Aliev, the director of the film “Homeward,” stated, “Russian soldiers and bombs are no different from their propaganda weapons, which may not kill people directly, but justify these atrocities or divert attention and shift the focus from the main thing. …the boycott of Russian cinema and culture is an attempt to cleanse the world of the propaganda of a terrorist state.” The International Festival de Cannes, one of the world’s most important film festivals, announced that official Russian delegations are not welcomed.

However, some people claim that the cultural boycott against Russia targets the wrong people. Opponents against the boycott movement argue that the boycott is targeting individual Russians rather than the political stance of Russia itself, having no effect in actually showing solidarity for Ukrainians in war. Tyler Cowen, a professor of economics at George Mason University, calls the Russian cultural boycott the new “McCarthyism” in his Bloomberg Opinion. McCarthyism occurred in the 1950s in the United States when Americans were accused of being “communist sympathizers” and were canceled from public life. He argues that the same false accusations and censored speech are currently happening in Russia. “It is simply not possible to draw fair or accurate lines of demarcation. What about performers who may have favored Putin in the more benign times of 2003 and now are skeptical, but have family members still living in Russia? Do they have to speak out?”

A similar claim is presented from a different perspective from artists. “Art shouldn’t be prevented by war,” Haehnsen Kan, a French artist in Moscow, tells ArtNet News, “it is important for Ukrainian artists to know that artists in Russia support them.” Many artists against the cultural boycott movement claim that there are many Russian artists taking risks to condemn the Russian government and support Ukrainians but that the boycott is limiting their freedom of expression.

The fact that many organizations are refusing to connect with Russian artists who made the choice not to criticize Putin openly is making two assumptions about the artists. The first assumption is to presume that Russian artists feel no fear in expressing their ideas against the authoritarian regime, and the second is that the artists are in favor of the Russian invasion just because they choose to keep their opinions private. Christian Solmecke, a media lawyer, shared with DW, “An employer can’t force a musician to say something political that he doesn’t stand for.” The opponents of the cultural boycott believe that the world should appreciate Russian artists who speak publicly about the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but shouldn’t put pressure on them to do so.

As controversial as the cultural boycott of Russia has become, the more practical concern is the effectiveness of the boycott in stopping the Russian invasion of Ukraine from doing any more damage. Alexander Melnikov, a Russian pianist told Financial Times that the cultural boycott does not have any real effect on Russians but simply increases the anti-western sentiment, “clustering more tightly around the leadership.” However, some believe that having a huge economic impact on Russia is not the purpose of the movement. The real benefit is “providing a symbolic stand as to what our belief is,” said Paul Isley, an economics professor at Grand Valley State University in Michigan, to NPR.

Whether the cultural boycott will work as an effective way to stop Russia is debatable.