The College Board: This data is no longer available

Claudio Schwarz on Unsplash

“Data”

February 8, 2023

“What language did you learn to speak first?” Malayalam.

“What college(s) setting do you prefer?” In the middle of a bustling city.

“What is your race?” Wait, what?

I stared at the screen, confused.Why does the College Board care about my race or ethnicity. What are they going to do with that information? To remedy my curiosity, I asked Google. A fifteen page long description by the College Board on adhering to the values of affirmative action and the reporting and usage of a student’s race/ethnicity data presented itself on the screen.

In 2016 the Advanced Placement Program, a branch of the College Board, announced that they would be introducing a two-part question regarding race and ethnicity to “align with U.S Department of Education guidelines and better serve [their] schools and districts.” These AP scores by race would later be made publicly available on their website. The reporting of this data was done so by race/ethnicity and state. A 2019 College Board report indicated clear score discrepancies between the majority and the minority in that the lowest average score on the AP exams was much higher in majority groups than in minority students. For example, Caucasian students had the lowest average score, just above a 2 while African American students had the lowest average score below a 2.

After much time spent researching the function of the race/ethnicity question, I gathered that it is simply used to accumulate data, and what individual institutions may or may not do with that information is entirely out of the College Board’s hands. This is where the function of the race/ethnicity question, and the data accumulated from it, could serve a bigger purpose.

Discrepancies in test scores by race are the biggest indicator of the work the government and society have left to do on the issue of racism in education. Brookings Institution reports on how standardized test scores such as the SAT reflect racial inequality in education, “a likely result of generations of exclusionary housing, education, and economic policy,” essentially highlighting that racial minorities who lived in less affluent neighborhoods received a lower quality of education over generations. This correlation and analysis was made possible by the SAT scores by race being publicly reported. It gives society and, most importantly, affluent entities such as the government and universities, the evidence they need to create policies that could effectively help address racial inequity in education. We know score discrepancies exist, and it is time we acknowledge it.

So why not do the same with AP scores? There is so much potential for this newly acquired data to help accelerate the path to racial equity in education, and having this data come from not one, but two streams of test takers, only increases the credibility of this data. The potential this data has to make a dent in the issue of racial inequity in education is immense, and if it means giving up some measure of my privacy, I will gladly do so.

However, in 2020, the College Board made an executive decision to pull all AP scores reported by race/ethnicity from all of their domains with no explanation or prior notice. What was even more surprising was that not only is the information not publicly available anymore but according to the College Board’s guidelines, private access to the data is highly restricted.

The guidelines further go on to read that “exceptions to these Guidelines will only be made upon the approval of a senior College Board officer and/or an internal Data Governance Council decision,” or if the party seeking this data has direct authority over the data they request to have access to. There is little evidence of the College Board releasing this data to the government, scholars, or the press, despite there being demand for the data. Further, there have been no public records of 2020 AP scores by race being reported on any mainstream media or newspaper. Jim Jump, former president of the National Association for College Admission Counselling gave his angle on the development in an article published by Inside Higher ED: “We need to figure out what the score discrepancies mean rather than pretending they don’t exist.”

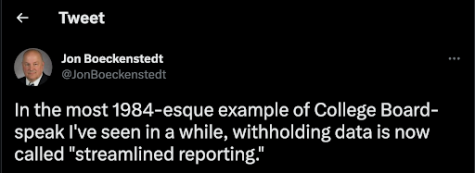

When the College Board faced speculation on the reasons behind withholding this data, the College Board came out with a statement that claimed this new development was to align with their new policy on “streamlined reporting”. Following the public statement made by the College Board, Jon Boeckenstedt, Vice Provost for enrollment management at Oregon State University, took to Twitter to share his disapproval of the College Board’s decision to no longer release AP scores by race, effectively holding the College Board accountable for not following through on their policy of transparency. He further characterized the College Board’s response to questions raised on their decisions as “the most 1984-esque example of College Board-speak [he has] seen in a while, withholding data is now called “stream-lined reporting”.”

However, this is not to say that the College Board is the villain here. Following the backlash the College Board received for their cryptic response to why they decided to withhold data, according to Jump, “conspiracy theorists ” have speculated that the College Board is actually embarrassed by the 2020 AP score by race reports. Jump expresses that he “sympathize[s] with the College Board if it fears that releasing the data will embolden the political forces looking to turn back the clock on attempts to make America a multicultural society and to increase opportunity for historically underrepresented populations.”

What is most frustrating is that the College Board does not seem to understand the importance in justifying their decisions, leading to even more misinterpretation and potential detriment to progress towards racial equity in education. If the College Board had presented a clear policy on what they plan to do with AP scores by race, I would be less skeptical of their motives to withhold AP scores by race.

The College Board still collects data on students’ race and ethnicity, and the question remains optional. Jump raises a valid question: “Why stop reporting the data? What has changed [(besides the testing format)] that makes the data no longer relevant?”

The College Board has all authority and power in withholding data they collect from students, but I would sincerely hope they don’t do so to protect their own corporate interest over what is truly at stake: racial equity in education. The College Board must recognize the value in publicizing AP scores by race and how it could help institutions address disparities in AP scores.