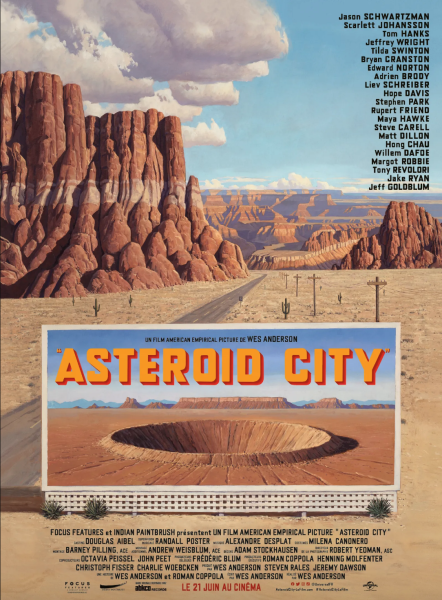

Earlier this year in May, when Wes Anderson’s new film Asteroid City’s poster was revealed, international cinema fans anticipated that this was going to be the best film of 2023. The cast list was full of big-name actors, including Edward Norton, Scarlett Johansson, Jason Schwartzman, Adrien Brody, Bryan Cranston, and Maya Hawke. After the release of Wes Anderson’s previous film, The French Dispatch, which received excellent ratings and reviews, many had high expectations for Asteroid City; what kind of story would be waiting for them in the theatres told by such skillful actors and Wes Anderson’s distinct stylized cinematography.

However, when the film was officially released in June, the film was met with reviews that were very different from what everyone expected. The star ratings were criminally low compared to some of his other movies (1-star ratings being the most common rating when searched on Google search engine in November), and quite a large portion of Rotten Tomato and Letterboxd reviews included opinions that the movie was too stylized, too pretentious, and too hard to understand. In his BBC review, film critic Nicholas Barber states, “Even Wes Anderson fans may be irritated by this ‘empty’ and ‘cartoonish’ film,” and some even stated that this was one of his worst movies as he was trying too hard to maintain the style that he ended up making a caricature of his own movies.

But was this really his worst? I would like to argue the opposite–I believe that Asteroid City is arguably one of his best films, alongside The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Royal Tenenbaums.

The film opens with a black-and-white television broadcast with the host (Bryan Cranston) introducing the audience to “Asteroid City,” a Broadway play produced by Conrad Earp (Edward Norton). He starts by explicitly pointing out that Asteroid City “does not exist” and is an “imaginary drama created expressly for the purposes of this broadcast.” Later, the scene shifts to the setting of the play, showing a desert town called Asteroid City in the Midwest, shot in brightly saturated pastel colors. The characters in the play gather in this small town to attend an annual Junior Stargazers convention. The convention is interrupted and accompanied by a series of strange events, including a visit of an extraterrestrial creature who mysteriously appears to retrieve the asteroid. Throughout the play, the characters struggle to grasp the meaning behind the bizarre happenings and the unusual things said and done by themselves. (Where does the alien come from? What do the pulses mean? Why did I voluntarily burn my own hand on the quickie griddle? Why am I preoccupied with wanting to be dared to do something?) The characters, most of them being teen science nerds, scientists, and parents of such child prodigies, strive to find meaning through logic and reason. At various points, when the film returns back to the black-and-white behind the scenes, it is revealed that the actor of Augie (Jason Schwartzman), the director (Adrien Brody), and even the playwright (Edward Norton) are also having difficulty understanding why Augie’s character acts the way he does.

It is true that many might find the film hard to understand at first watch. Like some of his other films, Asteroid City consists of multi-narratives and shifts between different dimensions, so the audience must stay focused throughout the film to get a full grasp of the message. However, Wes Anderson does make several attempts to make this more comprehensible for the viewers. One technique he uses is switching between monochrome and colored film to differentiate between the staged play and the reality behind the play. An interesting thing about his use of color is that he uses black-and-white to portray backstage scenes while using saturated colors to depict an imagined drama (the play), unlike many modern films that use black-and-white scenes to depict scenes that are “not real” such as dreams, hallucinations, or theatrical shows. The monochrome scenes are often shot to resemble a stage, especially when the camera zooms out or shows symmetry. Wes Anderson blurs the line between reality and play, which suggests that the characters in the play reflect the actors, and even attempts to break the fourth wall to connect with the audience watching the film.

In the big picture, Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City can be interpreted as a large metaphor for life, which is often very confusing and filled with events that seem to lack purpose or reason. People spend a significant amount of time contemplating and overanalyzing events in life, trying to make sense of everything and attach meaning to it. Wes Anderson suggests how useless it is to search for something that is unreachable and that people often forget to live in the moment because of this. The absurdist nature of this film reminded me of one quote by Terry Davis, when he stated that humans existing in the universe are just like birds looking at a computer screen. While the bird cannot comprehend what the computer monitor is doing, it does not panic but does the best it can to live its life. In a conversation between the actor who plays the character Augie and the director, Augie expresses he does not understand the play. “Do I just keep doing it? Without knowing anything? Isn’t there supposed to be some kind of an answer out there in the cosmic wilderness?” In response, the director states, “It doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story.”

Wes Anderson also audaciously suggests that the best way to find one’s place in this inscrutable, chaotic universe is through human connection. After this conversation with the director, Augie attempts a temporary escape from the play. Outside the fire exit, he encounters the actress (Margot Robbie), who was meant to play Augie’s deceased wife in Asteroid City. As the two recall the scene they would have had together if it weren’t cut from the play, she reminds Augie of his significance in the story, which motivates him to return to the stage and continue.

My personal favorite part of the film was the ending scene, when the characters start to chant “You Can’t Wake Up If You Don’t Fall Asleep,” a song composed by Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker. The lyrics imply that humans must overcome their inherent desire to find answers in life to live life to the fullest, perfectly summarizing the message of the film.

Countless reviews have argued that the film is “pointless,” but perhaps this is exactly what Wes Anderson intended. According to philosopher Albert Camus, absurdist art must teach us to accept the absence of reason instead of making grandiose attempts to present answers simply because there is none. The delivery of the seemingly frustrating and hopeless message through beauty is what makes Asteroid City the epitome of an absurdist masterpiece, allowing the audience to peacefully reconcile with the incomprehensibility of life and continue on—just like how Augie does.