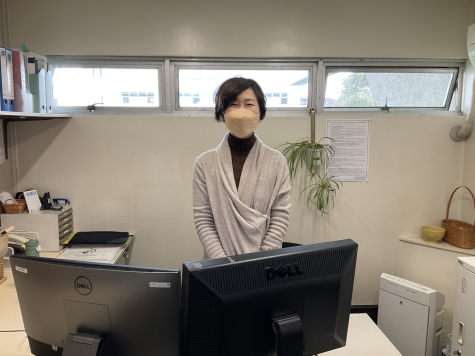

Ms. Pomroy

“My first memories of statistics aren’t positive. My education was through the British system, and I remember the first time I really had to do statistics was as part of A-level maths. I remember being one of those students who are like, “I can’t do this, it’s too hard!” But, I remember getting a test back near our exam time from my maths teacher, and I had gotten something like 67/68 and the mark he had taken off was for not rounding to three decimal places. My teacher had written on it: “Can we take this now as evidence that you can actually do statistics?”

When I taught back in the UK, I taught the statistics part of A-levels to students there. Initially, statistics wasn’t a passion in a way maths was a passion for me. When I came to Sacred Heart, I didn’t come to teach statistics, but coincidentally, the teacher who taught statistics left at the end of my first year, and that was how I started teaching the subject. At that time, I kind of felt like I hadn’t done enough statistics recently to feel comfortable and confident, so I then went to study more myself. I just feel like when teaching, even if you are teaching at one level, you need to be a bit further ahead. I think, perhaps, doing that really got me into it, because I finally felt like, “Yeah, I can do this, and I do understand it.” So, that’s when I got more passionate about it.

Being a statistics teacher played a large role in me doing further studies in statistics, so I kind of decided when I had done statistics, for a year, to do my master’s degree, in statistics. And then, I finished that at the end of 2010, and it’s like, okay, I’ve done so much statistics now, it’s gone way beyond what I needed to teach. So what am I going to do with it? It was like, “I know! I will take the next step! I will go on and do a doctorate, and that will give me the chance to use statistics!”

My interview for Durham University was on Friday evening, the week before the 2011 earthquake. I started in Durham that summer. I spent four weeks in Durham in the summer of 2011 and 2012. In Durham you have to do five modules, and they include statistics and also qualitative research, even though statistics tends to be associated with more quantitative research. I wrote three essays in the first two years, then moved into the thesis stage that took me six years. They usually take four years, but I took a year off because of other things going on in life, and then you get a year in the end, to write up, so it did take a long time. It was excruciating at some points.

When you do the research element of any doctoral program, they tell you that you have to add to knowledge. So I think finding the topic that I wanted to actually work on was hard. They say that what you actually start out doing as your research and where it ends up are very different things, and that was certainly true in my case. My research question changed loads over time. I reached a point where I was like, “How do I change my research so that it makes what I’ve done up to now worthwhile?”

The guy who interviewed me on March 4, 2011, said, “Standardized testing is a big topic at the moment, so how about, putting your thesis around that?” So I did qualitative research, looking at the use of standardized testing in international schools in Tokyo.

When students get feedback from standardized testing, we teachers also get similar information, which should then be used to inform our teaching. But how accurate are they when used in the international community if they are designed for American schools or Australian schools? Because, for instance, international schools have ESL students, where you have differences in language and culture. I then came to question, “The CollegeBoard is looking at being ‘college-ready’ but for US colleges. How do the cultural and linguistic differences impact this ‘college-readiness’? How much does it impact the information that we get?”

There were many moments where I wanted to give up. I had members of my family being quite sick over the last ten years, so when you are trying to deal with, “I’ve got a job,” and “I’ve got to deal with this emotional situation,” it’s also hard to keep going with the research. Sometimes what kept me going was encouragement from people around me, so I remember one day, thinking “I’m at the end, this is it, no more,” and then talking to Ms. Saso. She’s like, “You’ve got to keep on going.” So people’s faith in the fact that I could do it, their encouragement, and asking “How is it going?” helped me because I felt like I didn’t want to let them down.

Being able to balance out my academic, personal, and professional life went through phases, I mean… when you’re doing research, you’ve got to do lots and lots of reading— my bibliography was about 15 pages. When I started to do all the reading, I had to try to devote weekends to do that. And then you go into the research phase, and, when you’re interviewing people, you’ve got to work around their schedules. When I went into the final phase, the final writing up, it was summertime. For me, that was it. I thought, “This is the summer, it’s going to be done, it’s going to be finished.” And so, at my parents’ house, I’d be getting up every morning, having breakfast, then type type type, have lunch, back to the dining room table, type type type. And, of course, the process never goes as quickly as you want. So then, when I came back to school, it was like, ok, work, finish work, go home, start working on it, try doing a couple of hours, and then I worked on the weekends.

When I was finishing it, the Rugby World Cup was on, and I was there, so somebody said to me, “Set yourself limits, so yes, you can go watch England vs. New Zealand, if you have done these many words in the morning.” I do also advocate getting sleep, I kind of finished work at nine-o-clock in the evening, I’d have a cup of tea and then be in bed at ten-o-clock, and then, even on the weekend, I was up at 6:30 and working. So, I think having an idea of timing was very important.

Just making myself go sit at the table and not procrastinating was important. I have learnt over the past year that procrastination is not time-wasting, it’s fear. So when work came back from my supervisor, I would read it, and be like, “I can’t do that, I can’t do that, I can’t do that.” I would have to get over that and say, okay, let me try and work with this point, and just break it all down. I think, when you are finding difficulty in something, what I found helpful was, rather than thinking about the whole picture, just find something small that you can make a little bit of progress with. Even if it’s reading one article (although they can be quite tedious sometimes), at least you try and find something that makes you feel like you’re still working towards your goal. Just keep moving forward.

I think the highlight of completing the doctorate was the day I submitted the thesis, and then got a day to defend it. Because of COVID-19, that was through Zoom, and I don’t think I actually knew until that day that I had any chance of passing. So, that day was quite emotional. A standard result is minor corrections, and they’d given me this result, so I thought, “Oh my gosh!” I think there were tears. After I worked on those corrections, I sent it back to the internal supervisor because there wasn’t a lot to do, and then he came back and told me “Yes, it’s ok.” And then I actually had to put it online and putting it online was that final moment where I was like “Yes, this is over. It’s finished. It’s done.” And that was just so much relief. It’s funny, you kind of think there’s going to be this one major moment of excitement. I haven’t had any major moment of excitement. I’ve had some big moments of “Thank goodness it’s all done,” and a feeling of relief, and those were the big emotions for me.

I certainly learned a lot doing it. A book I was reading in the summer said that the purpose of finding new knowledge is for somebody else to look at your research and to then start asking questions, and say “Ok, well, you said this, but there’s also this information that you didn’t think about, or there’s also this kind of focus.”

This idea that we should be able to use the information from testing in schools, certainly led to me questioning, “Well, how do we manage to separate what we call in statistics ‘the noise’ from the useful information?” What do teachers need to know about the uses of assessment? But the point is, teaching is a very individual profession. We have our own ways of doing things, and I think you never quite know who knows what. The data analysis side is the testing coordinator’s job. But what do we do with the information, and how it impacts teaching depends on the individual teacher.

There is a lot going on with standardized testing, especially in America. You’ve also got the anti-testing movement now as well because they’re starting to understand that actually, the tests are not a measurement of the school, even though parents have been encouraged that it does. Educating parents about assessment literacy is important because then they can understand what testing results mean. It’s not just teachers that need to understand what testing tells you, parents need to understand that as well. But I don’t think standardized testing is going to vanish quickly, because there’s been a lot of hype about its impact on education, and for the governments around the world, this idea of measurement is an important thing. I hope that it evolves into a way where it is used not in the carrot and stick approach, but in a meaningful way.

My goal as a teacher is just to help students do the best they can. I worry that everybody sort of thinks, “I have to be able to do calculus by the end of grade 12.” That’s not necessarily everybody’s goal. They say there is a seven-year difference in people’s maths abilities, so what some people are able to do at 11, some people won’t be able to do until they are 18. My goal is to help students get to the best place they can get to and to be comfortable. So, later on, if they come back to maths, it won’t be that subject that they say, “Oh, it’s something I wasn’t very good at.” I hope they will be willing to take that challenge.” — Ms. Pomroy