South Korea and Finland – role models for the ideal education system?

In the recent 21st century, Finland and South Korea’s education systems have captured much attention, boasting students that consistently rank among the top academic achievers worldwide. South Korea’s method of education is often deemed extremely demanding, focusing on memorization and test-taking, while Finland’s method prioritizes a laid-back, holistic approach with a more student-centered outlook. But how do these two different countries manage to repeatedly produce such successful students with vastly contrasting educational tactics?

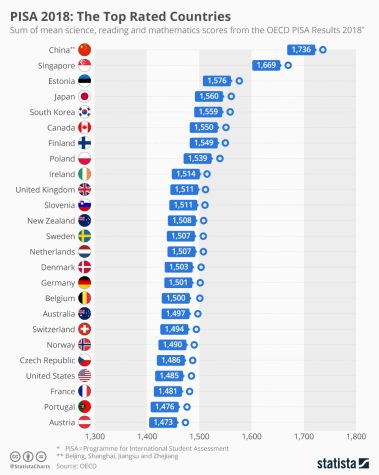

South Korea’s rigorous education system – at times considered too extreme – seems to be working, as demonstrated by the 2018 PISA scores which rank South Korea among the top 5 highest overall scores out of 79 countries who participated. PISA is a “global program whereby around 600,000 15-year students from different countries are put under a two-hour test to gauge their skills and knowledge, mainly in science, reading, and mathematics.” Finland follows closely behind, ranking 7th place overall, despite practicing completely different approaches to education from South Korea.

In South Korea, success in education certainly doesn’t come easy; the students pay the price with crushing academic pressure and grueling work both in and outside of school. “It’s normal for students to spend over 12 hours in school and cram schools alone,” says Heejae K. (‘25), a South Korean student. A Korean student can spend up to an average of about 12 to 16 hours per day in school and hagwons – or cram schools – which often start from elementary or middle school and continue to extend into high school. It is typical for students to learn ahead of their learning curriculum from early on in their academic years, something that parents push for their children to do in cram schools. “There are kids in elementary school who have finished the high school math curriculum,” Heejae notes, “the academic stress is normalized in Korea.” The steadfast mindset of Korean education holds the belief that the number of hours invested in studying rewards students with a successful grade, even if it means sacrificing an individual’s mental and physical health.

Finland, however, tells a different story from South Korea. There is significantly more emphasis on mental health for students in Finnish schools, providing guidance and counseling services focused on the individual’s well-being. The stable establishment of guidance systems boosts mental health for students, giving a positive outcome on academic success. Not only are students given a reliable guidance system, but they also have plenty of time to rest between classes as well as shorter school hours in general. School may start from 9:00–9:45 AM and end at 2:00–2:45 AM, with long breaks in between every class. Time spent on homework assignments outside of school is minimal to none, and allowing fluidity for students to explore outside of the classroom is inherently part of the Finnish education system. Their ability to accomplish more with less time is a testament to the research-tested benefits of breaks, something the Finnish school system has been proving to be greatly effective. Unlike South Korea, the amount of time spent studying in a classroom is not viewed as the only source of academic success. School curriculums are not focused on competition between students — they lean towards trying to enhance individual students’ strengths without comparing them to each other.

Contrary to Finnish schools that believe in creating a non-competitive learning environment, Korean high schools use an academic grading system that evaluates students by their grades and ranks them into corresponding numbered positions. Naturally, this ends up promoting a highly competitive atmosphere within the student body. A cumulation of academic stress from long hours of studying in hagwons combined with the competitive environment triggered by the ranking system in schools tends to lead to poor mental health for students, an unfortunate reality for many Korean teens and a staggering polarity between the two countries. According to data from statista.com, South Korea’s high school student suicide rate was 4 in every 1,000 students in 2021, an alarmingly high statistic.

Other than the normalization of sacrificing long hours in cram schools, Korean students also carry the looming burden of taking suneung, a national standardized test that determines which university one goes to – equivalent to that of the SAT in the United States. The Korean suneung is considered to be the final, most important stepping stone of a student’s entire high school career, an eight-hour-long exam that controls an individual’s immediate future. The immensity of this exam is demonstrated through some of the extreme measures taken by the whole country to accommodate the students taking the exam: construction work is delayed, planes are not flown, and military training is stopped in fear of disrupting the students. For students taking the suneung, their future university placement and job is on the line, a hefty price combined into one ultimate test.

Finland also has a standardized test called the National Matriculation Exam, though it is by no means taken with the same severity as Korea’s suneung. The exam is not required for high school graduation or a university entrance. Organized by the Finnish matriculation exam board, the test consists of four open-ended exams with a mixture of questions ranging from problem-solving skills, analysis, and writing. It should be noted that with the exception of the matriculation exam, Finland still relies heavily on a more localized system that deviates from the previously centralized system, which focuses on external testing. Teachers with professionally trained backgrounds prepare a productive and thoughtful curriculum following the national standards of education.

While both countries produce highly successful academic achievements, their stark differences in the educational system bring out an important question: is attaining successful education under mentally demanding and stressful conditions worth it? South Korean students earn impressive grades but at the expense of deteriorating mental health. Finnish students also manage to be as successful in academics without the same downside on mental health, introducing a new path for how education can flourish without using academic pressure.