When the colonial mindset rears its ugly head

The BBC’s documentary “The Modi Question” stirs controversy amongst Indian audiences

Government Open Data License - India

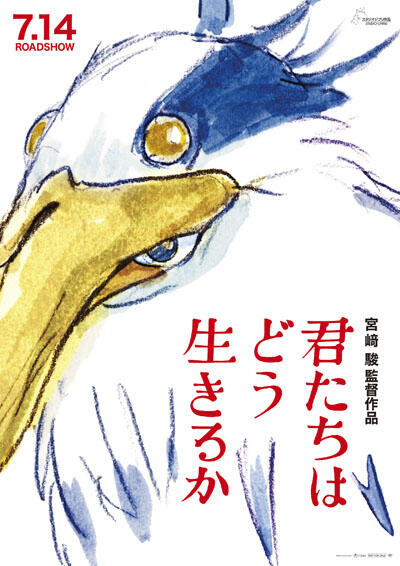

Prime Minister Narendra Modi meeting Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, of the United Kingdom, in London in 2015.

May 10, 2023

In the recently released two-part BBC docu-series, “The Modi Question” it was made abundantly clear how the British media views India, and many people are not happy.

Coexistence of vast diversity is perhaps what every Indian takes great pride in. I know I do. While we all wish for harmony amongst the many different cultures and beliefs, the Hindu-Muslim relationship is one we struggle to maintain harmony in. The discourse has resulted in a multitude of bloody conflicts India is not proud of. One of the most ruinous of which, was the 2002 Gujarat Riots. The losses experienced are indescribable, and the pain and hatred that stemmed from the riots remain an ugly memory. But this painful incident took place 20 years ago. Many people want to forget the agonizing past and are learning to move on.

Apparently, the BBC isn’t.

“The Modi Question” in its two episodes explored the rise of Narendra Modi, and the science behind his popularity while also tackling the controversies his career has faced: his alleged role in not only insufficiently defusing the violence but inciting it during the 2002 riots.

The crux of the documentary heavily relies on the British High Commission report sent to the then British foreign minister Jack Straw on the 2002 Gujarat Riots. Straw, who claims to be well-versed in India’s history of religious discourse and the political implications that came with the new BJP government, told The Wire that he stands by the claims of “those who were on the ground,” that Modi was responsible for the riots. The report further claimed that they felt the incident “[had] all the hallmarks of ethnic cleansing,” yet the evidence as to why that was the consensus has not been revealed. After the report was sent to the Foreign Ministry in London by British representatives in India, Straw told The Wire that he recalls that he contacted the Indian Foreign Ministry; however, struggles to recall what the response was. He, who knows India so well, has chosen to speak upon this issue so many years ago, fails to go on record about an integral piece of the story. While the documentary did include different sources, they were either renditions of the same bias that echoed Straw and his colleagues’ report, or opposing views were represented in a way that further amplified the main bias: a British-centric perspective on human rights issues in India.

Before scrutinizing the BBC’s characterization of the involvement of PM Narendra Modi in the Gujarat Riots, let us review the facts and context of the matter. In 2002, India was governed by the Congress Party (BJP opposition) and Narendra Modi was the Chief Minister of the state of Gujarat, where the riots took place. Subsequently, after the riots had died down, a special investigation team, appointed by the Supreme Court of India probed Gujarat and inquired and investigated the Gujarat state government, including the current Prime Minister Modi. In 2002 when Congress was India’s ruling party, the Supreme Court gave then Chief Minister of Gujarat Narenda Modi what they called a “clean-chit”, or cleared him of all charges. In 2022, the Supreme Court reviewed the 2002 Gujarat riot case leaving Narendra Modi free of charges for a second time.

The Gujarat riots were examined with the utmost priority in investigation and justice, virtually passing all levels of the Indian judiciary, yet the BBC is not convinced by this verdict.

While it cannot be claimed with conviction that the Supreme Court’s decisions equate to fact, and seeing as Modi was the Chief Minister of the state where the riots took place, we cannot assume he takes no responsibility for his role in handling the riots. Still, there is insufficient evidence to hold him responsible for inciting the violence.

The release of the documentary was a PR disaster for the Modi administration to say the least. The documentary was banned, claiming that it threatened the sovereignty of India.

The Indian government’s sentiments were that they weren’t just banning a documentary, but denouncing its attempts at alleged propaganda and defamation. The banning compelled students to conduct illegal watch parties of the documentary that led to squabbles with local police. Not to mention yet another opportunity for the BBC to comment on the press freedom implications of this decision.

Dr. S Jaishankar, Foreign Minister of India told Brut India that the debate is not just about the documentary but the politics. Jaishankar said, “This is politics by other means.” Further claiming that the timing of the documentary did not seem accidental to the administration. This begs the question: Is the documentary in the interest of global human rights or is there an ulterior agenda? What is the significance of the timing of the release of this documentary?

As Palki Sharma from CNN-News18 illustrates for us, currently, the UK is in grave economic turmoil, a cost of living crisis, and economists are predicting the longest and worst recession in the G7. Not to mention the BBC’s chairman, Richard Sharp, is under investigation for conflict of interest. Yet, the BBC (a British government funded public news outlet) chose to use its capital on an opinion piece on Indian PM Narendra Modi and his role in a conflict—an internal one—that occurred twenty years ago.

The BBC went on record to say that the timing of the documentary was due to a delay in source material, and vehemently reject any accusation of neocolonialism or propaganda. Apparently, the British foreign ministry’s official report on the Gujarat Riots had only been released to the BBC 20 years after the incident. The BBC has also further brought up the argument that the Gujarat Riots being an internal conflict does not negate the fact that it is a human rights issue, therefore a phenomenon in the interest of all, not just India. Yet, I find it hard to give credence to the justifications the BBC has offered.

I disagree with some critics claiming that the BBC is making a mockery out of the Indian Justice system, implying that the BBC is not convinced by the Indian Supreme Court’s decisions. Yet, it cannot be ignored that the way the documentary centers around PM Modi’s rise in Indian politics to his role in the Gujarat Riots was intentional. The picture of Narendra Modi being painted as a Hindu nationalist is undeniable. Not that this term is foreign to PM Modi, and even frequently used in national media to refer to the Prime Minister. The Indian press has heavily criticized Modi’s policies as reflecting that of a Hindu nationalist.

The BBC is an international news outlet, but the bulk of its audience lacks the context of Indian politics, and the BBC has provided none. By doing so, the BBC is painting an extremist image of India, because while the ruling political party and prominent politicians may be Hindu nationalists, the country is certainly not.

There should be more opportunities for dialogue that focus on keeping secularism intact in India. However, having the BBC retell a calamity from 20 years ago is not the way to go about it. To me, this documentary reignited hatred and pain, rather than shedding light on the core issues with the tensions in the Hindu-Muslim relationship. It is not as simple as the BBC making a documentary and enlightening everyone on the supposed cause of the issue, if so we would not be having this debate.

The BBC has all editorial autonomy to assess and analyze the Gujarat Riots. Yet, I struggle to understand why the BBC is telling the world about the human rights violations in my country? Yes, the BBC has much more international reach than local news outlets, yet this issue could have been approached in numerous other ways. For example, collaborating with local news outlets or bringing variety to the source material, especially those from India.

India does not need the BBC to be our white knight, teaching us to be civilized, human rights following people. We have had enough of that, and we’ve got it from here.