Three-thousand steps forward

Sanjana Rapeta

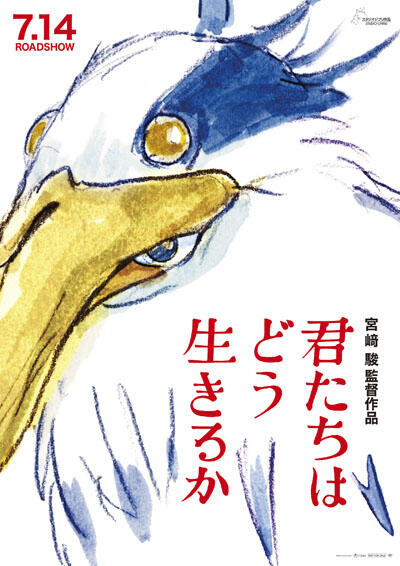

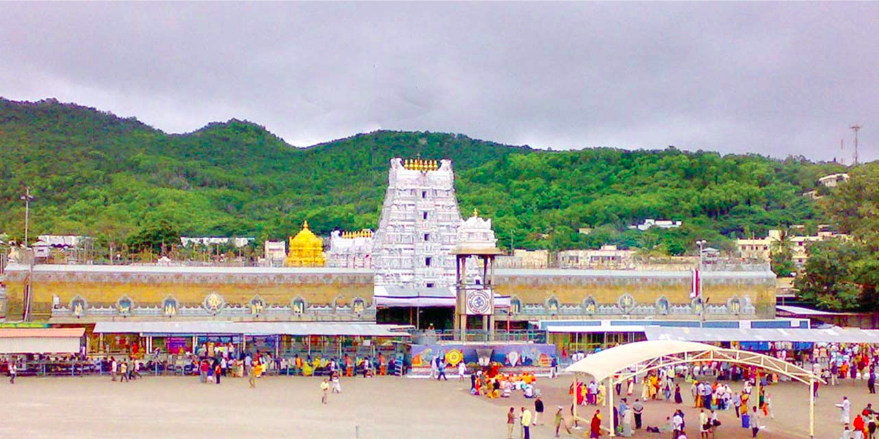

The exit of Tirupati Balaji during the winter, when the crowd is significantly smaller.

The sun was gradually rising, transforming the dark shadows of mountains into glittering, gleaming peaks. Loudspeakers were proudly perched high on poles chiming mantras that could be heard from the other side of the mountain. The morning was perfect. Children yawned loudly as mothers gently patted their backs. Like removing your shoes at the entrance of your home, I took off my sandals and felt the rocky ground, which was warm, despite breathing in cold, harsh air.

So early in the morning, I could already see the line of clean, empty buses arriving, and families quickly picking up their luggage and pushing themselves to the front. Our family, however, steered away from the group, trekking until we arrived at the starting point. I felt my mother brush her fingers with red powder taken off a miniature Lord Vishnu of the step dabbing a red, powdery wetness across my forehead, and before I knew it, I was standing on the first step of the three-thousand step staircase to the top of the mountain, the destination that most had taken the bus to reach.

A metal roof was sitting atop the stairs, its long, concrete legs supporting either side like a torii gate. Despite the ceiling’s fragile appearance, it stayed undamaged in India’s treacherous climate. I remember how adults talked about the pain they endured to get to the top, and I briefly morphed into a typical teenager as I scoffed at the tiny steps in front of me. However, as I waited for my parents to hand in their tickets, my arrogance morphed into appreciation.

Tirupati Balaji stands out from India’s thousands of temples as one of the most auspicious and holiest pilgrimage sites in the world, with more than thirty-five million traveling up the seven holy hills to see the idol the temple houses, Lord Venkateswara. For Hindus, visiting Tirupati is a once-in-a-life experience, especially as it’s located in the very south of India, while most live in the North. Even though we could afford to go there multiple times, it felt like a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I was finally here – in Tirupati.

For me, every trip to India had consisted of the same two factors: visiting relatives and historical sites. My parents did this because they wanted my sister and I to bond with our heritage and home country. This process, however, was tiring, traveling so many places that the primary outcome of these trips was only exhaustion. Travelling had become a burdening chore, rather than a freeing experience. It was for this reason that when my parents booked tickets to Tirupati, I felt genuine excitement. Tirupati was not only a pilgrimage site; it was a hidden gem, free from the urbanization that unravelled throughout India. Here, people didn’t take out their phones and snap pictures, or toss finished soda cans to the ground; they experienced life-changing revelations and a happiness that transcended worldly pleasures. This was my opportunity to find true meaning in my travel experiences.

However, as I stood before the staircase, I was dumbfounded by how ordinary the staircase looked. Sure, some “holy” paints were splashed onto the staircase that gave a little colour, but underneath them were the standard, grey cobblestone stretching out like any other public staircase. Still, I decided to ignore this mundane thought and focused on energizing and motivating myself for the steps ahead. I raced through the first several hundred steps, and saw the numbers on the stairs slowly climb up: a hundred, hundred-fifty, two-hundred…

After the first thousand steps, I was disturbed by the brittleness of my legs. My breath, which was even before, now was being puffed out. I stopped to pause and catch my breath every ten minutes. I grabbed my water bottle at the side of my bag, only to realise that I had drunk it all.

The stairs had changed as well—I had been so distracted counting my steps that I hadn’t noticed the small elevations I saw before had somehow transformed into looming, vertical staircases.

To make a person struggle this hard, there must be something truly amazing at the top. A magnificent view? Or maybe I would have an unprecedented stroke of wisdom, and my bad habits will vanish completely. I justified the struggle by imagining the glory that would come to reaching the top, despite ultimately knowing that I was hating traveling like this. I felt no joy or elation like I had expected, only exhaustion.

When I passed the two-thousand mark, I was more than drained. Sweltering heat replaced the cool, crisp air that I felt earlier in the morning. My legs were two raw slabs of meat. I continued climbing, but it soon felt like a blur. I simply focused on climbing.

Then, at the corner of my eye, I saw it – the ending point. It was only a hundred steps away, but it felt impossibly out of reach. For a brief moment, I considered resting before the final summit. But I shook my head, adjusted the straps on my bag, and willed my legs to move forward, one step after another.

When I reached the top of the staircase, all I felt was relief. I stumbled to a nearby bench and collapsed, panting for a moment before shrugging my bag off my shoulders and dumping it next to me. It felt like heavy bricks had been taken off my feet.

However, while I searched for a shop that sold water, the woman next to me bragged about the expensive trinkets they were going to buy for their homes. I saw a few men laughing near a fountain—one held a can of beer in his hand. Kids ran up the final steps and screamed to their mothers for ice-cream.

I felt a wave of disappointment wash over me. There was nothing spectacular about this place – no beauty that made the experience profound. I felt no satisfaction from being at the top. What was the point of struggling, if your work leads to nothing? I finally realized: this could not have been more similar to my other travel experiences.

I wanted this trip to be different from the others, but it wasn’t. My desperation for this experience to mean something more had left me feeling more exhausted than I ever before—exactly what I was trying to avoid.

I recalled the other people who climbed up the steps – the old ladies wearing saris, the little toddlers waddling up each step. I realised that most sat on the sidelines, eating homemade curries and juice boxes, while enjoying the beautiful scenery, which I had never stopped to look at. Few were actually climbing, and even then, they took their time. They were simply enjoying the company of the people around them.

Nothing is ever perfect, or the way you want it to be, but an experience becomes better when you let go of expectations and appreciate it for what it is — even if it means climbing several thousand steps to realise it.