World politics reflected in the 2020 Summer Olympics

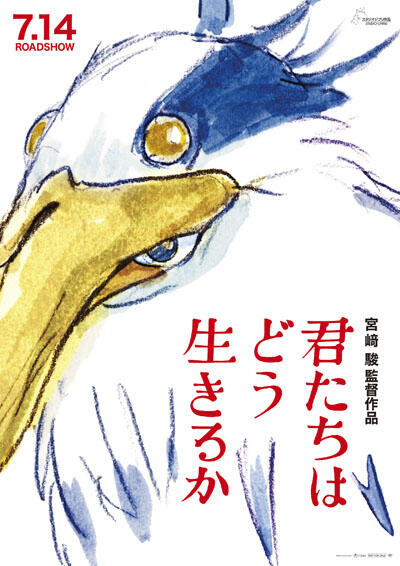

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Image of the Cameroonian weightlifter Cyrille Tchatchet who competed for the Refugee Olympic Team in the 2020 Summer Olympics.

November 17, 2021

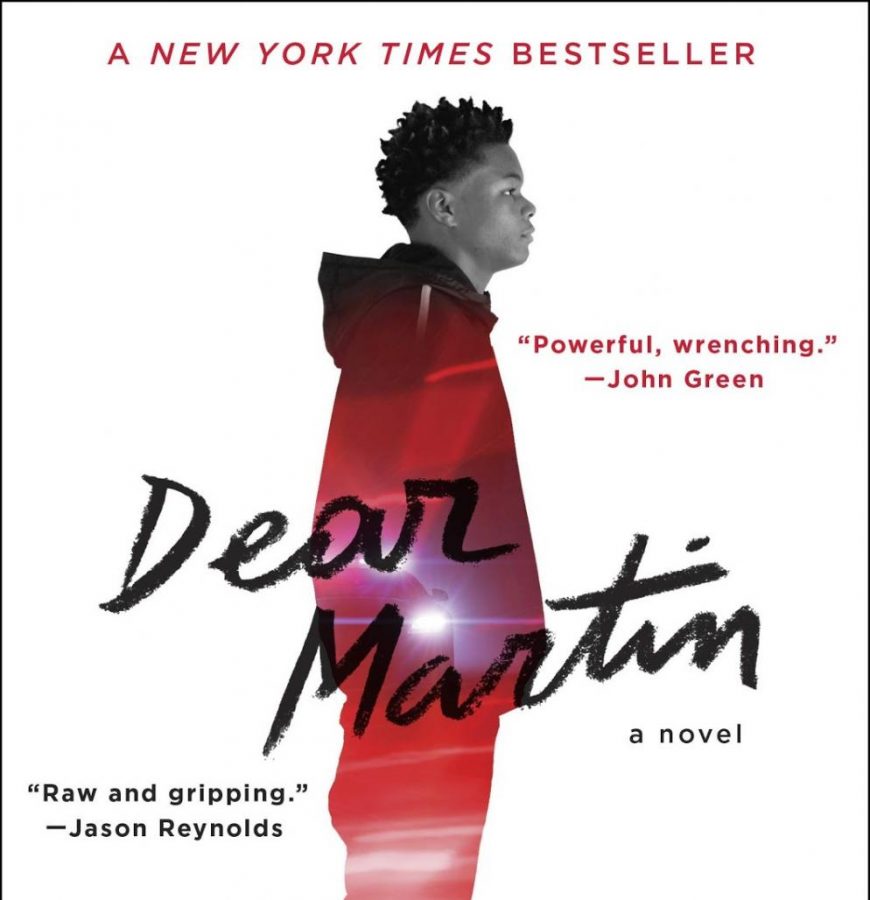

After a one-year delay, the 2020 Summer Olympics and Paralympics were held here, in Tokyo, in the midst of a global pandemic. Because of this, the responses were mixed: some believed that it was inappropriate for Japan to host an event that is supposed to represent peace when COVID-19 cases were soaring and some thought that it was worth the trouble. On the other hand, it was undoubtedly a great year for the Refugee Olympic Team. 29 athletes from 11 countries, including Syria and South Sudan, competed in 12 sports: athletics, badminton, boxing, canoeing, cycling, judo, karate, taekwondo, shooting, swimming, weightlifting, and wrestling in the Olympics. Six athletes from four countries competed in four sports: Para Athletics, Para Swimming, Para Canoe and Taekwondo in the Paralympics. That said, the 2020 Summer Olympics shed light on the political turmoil that is going on in the world.

As a result of 65 million people being displaced from their homes due to conflict or natural disasters in 2015, over one million refugees fled to Europe from the Middle East, Africa, and Central Asia. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) then responded by establishing a Refugee Emergency Fund, donating $1.9 million to international aid agencies to incorporate refugees into sports and announcing that they would be inviting refugees to compete at the following Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Ten athletes from Syria, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Ethiopia successfully participated in the 2016 Summer Olympics as members of the Refugee Olympic Team, and two athletes from Syria and Iran participated in the Paralympics of the same year as members of the Independent Paralympic Athletes Team. Since then, the Refugee Olympic Team has been a symbol for inclusion and hope. In the words of Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees and Vice Chairman of the Olympic Refugee Foundation (ORF), the team showcases “what is possible when refugees are given the opportunity to make the most of their potential.”

In addition to the ongoing pandemic, the world experienced countless conflicts through 2020 to 2021 and this was reflected in the games. A Belarusian sprinter Krystsina Tsimanouskaya made headlines when she refused to take an order from her team to fly back to Minsk after complaining about the national coaching staff at the Olympic Games on her Instagram account. “Some of our girls did not fly here to compete in the 4x400m relay because they didn’t have enough doping tests,” Tsimanouskaya told the news agency Reuters. “And the coach added me to the relay without my knowledge. I spoke about this publicly. The head coach came over to me and said there had been an order from above to remove me.” This incident highlighted the growing conflict in Belarus that erupted last year in a wave of protests against the Belarusian government and President Alexander Lukashenko who has been in power since 1994. The sprinter has been granted a humanitarian visa by Poland, one of several countries that had offered to assist her.

Similarly, Myanmar soccer goalkeeper Pyae Lyan Aung sought refugee status in Japan, fearing persecution in his home country. In a match against Japan, he gave a pro-democracy three-finger salute during the national anthem in a match against Japan, with a message: “We need justice” written on his finger. Like Belarus, Myanmar experienced civil unrest. Earlier this year, the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) claimed that the results of the elections were illegitimate and launched a coup d’état deposing the democratically elected members of the country’s ruling party, the National League for Democracy. In response, the Japanese government announced that it would allow Myanmar nationals to remain in the country for up to one year. Initially, the goalkeeper utilized this policy, which granted him a “designated activities” visa allowing him to work and stay in Japan for six months. However, he changed his visa status to become a long term resident, permitting him to stay in the country for five years and become a trainee of YSCC Yokohama.

Unfortunately, while Tsimanouskaya and Aung successfully found refuge in other countries, this was not the case for the Ugandan weightlifter Julius Ssekitoleko. Ssekitoleko was due to return home after the latest international rankings, which considered him as not meeting Olympic standards, were released after his arrival in Tokyo. However, on 16 July, he went missing from his hotel room in Osaka Prefecture leaving his luggage behind with a note indicating that he was going to work in Japan instead of returning to his home country. Five days later, the police found him in the city of Yokkaichi in Mie Prefecture. Upon his return to Uganda, he was held in custody for six days under the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of Uganda.

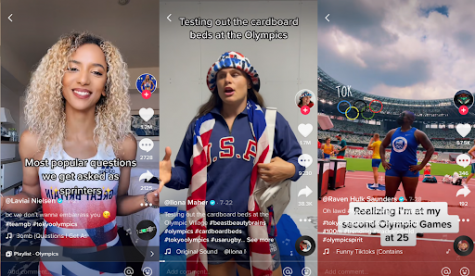

Japan has long been criticized for its restrictive immigration policy and the refugee recognition rate, as a result, stood at 0.4% in 2019, which is a drastic difference from Canada and the United Kingdom, which recorded percentages of 55.7% and 46.2% respectively in the same year. Last year, Japan granted 47 individuals refugee status and 44 individuals special residence permits for humanitarian reasons. While the responses from the Japanese society towards the Refugee Olympic Team were limited due to the lack of media coverage. Some showed their astonishment that athletes such as Tsimanouskaya, Aung, and Ssekitoleko felt unsafe in their countries and that they had to seek refuge during the Olympics on Twitter. For example, one user tweeted that they were surprised that some athletes did not want to return to their home country and another tweeted that they learned about the Refugee Olympics Team for the first time. Of the three athletes, Tsimanouskaya seemed to receive the most positive response, possibly due to her seeking refuge in Poland rather than Japan. Aung received very mixed responses and Ssekitoleko received some critical responses, due to him going missing in Japan under the state of emergency.

The 2020 Summer Olympics and Paralympics highlighted the successes of the Refugee Olympic Team. However, the momentum may be disrupted. China’s negative attitude towards the UN High Commissioner for Refugees might affect the IOC’s decision to send the Refugee Olympic Team to Beijing for the 2022 Winter Olympics and Paralympics. That said, with the 2024 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in Paris partnering with Techfugees, an international NGO on refugees, it is very likely that we will be able to see refugees participating in sports in the following Summer Olympics.