A Sacred Heart is what we need now

Photo Credit: International School of the Sacred Heart

All students and teachers from the kindergarten, junior school, middle school, and high school gather in the playground to celebrate the school’s annual event, Japan Day.

Michael Schur, the creator of many American hit sitcoms including the recent 97 percent Rotten Tomatoes rated show “The Good Place”, said in his interview with The New York Times magazine that the “temptation will always be there to go” but that “everyone should try harder”—“including me.” He was explaining the message that he intended to relay from his most recent work, which dealt with comedic eloquence the moral philosophy of the human experience — why should we be “good”, and how can we become “better”? It’s been two months since the final season of the show ended, but the essence of the four years-long journey that Schur took on with the six souls in the “Good Place” is captured by this one question to us all: “Do you give up or do you try?” And the answer lies in the very title of a recurring reference in the show, T.M. Scanlon’s 400-page dissertation, “What We Owe to Each Other”.

The conclusion is that we need to be “good” because that is “what we owe to each other”. Just like Schur displayed through his microcosm of six characters, we do not live in this world alone. In fact, it would be an understatement to assume that Schur’s universe is reflective of our much more complicated world of 7.8 billion people. The sheer number of people we come across in our lives is bound to be more than “six”, and to mathematically calculate the different paths someone else could have taken if we had (or hadn’t) made a choice is impossible and, quite frankly, pointless. We simply cannot live life without affecting anyone else’s lives, and as Spinoza wrote, “we are all profoundly linked in countless ways we can hardly perceive.” Once we realize the inevitability of this amorphous social net that is exponentially expanding and thus our influence on others — both good and bad — it becomes natural to focus on the communal values that we hold as not only as individuals but also as responsible members of a group. But how does Spinoza’s assertion that “a discrete individual” is “[fictional]” stand in the 21st century, the age of individualism?

It’s 2020 now, and, for good reason, we are fighting for individualism; we want individual rights, individual freedom. While there are many interpretations of the definition of this word — “freedom” — our implications of this perhaps jaded term in today’s largely westernized world is founded upon the ideal of the American Dream, the belief in egalitarian success and social mobility. As James Adams, the writer who first coined the term “American Dream”, wrote, the concept “has been a dream of being able to grow to fullest development as a man and woman, unhampered by the barriers which had slowly been erected in the older civilizations”. “Freedom”, therefore, refers to this “[ability] to grow”. I have no problem accepting this. It is just that I urge people to never undermine the significance of what follows after in this sentence: [ability to grow], “unrepressed by social order which had developed for the benefit of classes rather than for the simple human being of any and every class.” In other words, my freedom should never put your freedom at stake, or society’s. And with this important note in mind, I sometimes question if our cultural demand of individualism and personal “freedom” that overlooks the entitled “freedom” of others is too radical, if not entirely wrong.

Tim Ferriss rose to popularity after the publication of his first self-help book, “The 4-Hour Workweek”, which was based on his own entrepreneurial success. Since then, he has published four other top-selling books of the sort.

“[Rigging] the game so you can win it” is how Tim Ferriss, the American life-guru/entrepreneur/best-selling author/podcaster — in other words, the epitome of a 21-century celebrity — puts it. Ferriss, who is best known for his five #1 bestselling self-help books, “The 4-Hour Workweek”, “The 4-Hour Body”, “The 4-Hour Chef, Tools of Titans”, and “Tribe of Mentors”, basically gives people advice on how to become a young, white, millionaire businessman with six-packs. He lectures about becoming an individual through traveling the world, which is obviously only possible because of the “4-Hour Workweek”, and inspires other young men and women to dream to do the same by giving pro-tips on things like “[how to travel the world] with only a carry-on bag” and “[how to] hack the airport”. His works are undoubtedly resonating with many around the globe who seek to improve their lifestyles, and Ferriss’ entrepreneurial success certainly indicates his generation’s desire for such “freedom”.

None of this is news nor disappointing, really, but it is some of his specific “hacks” to “play the system” and “win the game” that I find irksome. One of the tips that struck me as shocking, for example, was his suggestion to “[place] a cheap starter pistol inside [your luggage] and [declare] at the check-in counter that [you’re] carrying an unloaded and locked firearm” to make sure that your luggage doesn’t get lost. Obviously, the feasibility of this “hack” is questionable as it is quite the hassle to request a T.S.A.-approved lock in the first place, and if approved this “hack” doesn’t trespass any legal code; however, it’s his complete dismissal of communal concerns that I find problematic. As Frank Bruni, The New York Times columnist, commented, it is “his emphasis on personal advantage over the public good” that is wrong in its core. If every follower of Ferris indeed decided to prioritize individual efficiency and productivity over society’s values and our entailing responsibility, I don’t see how we would be paying back “what we owe to each other”.

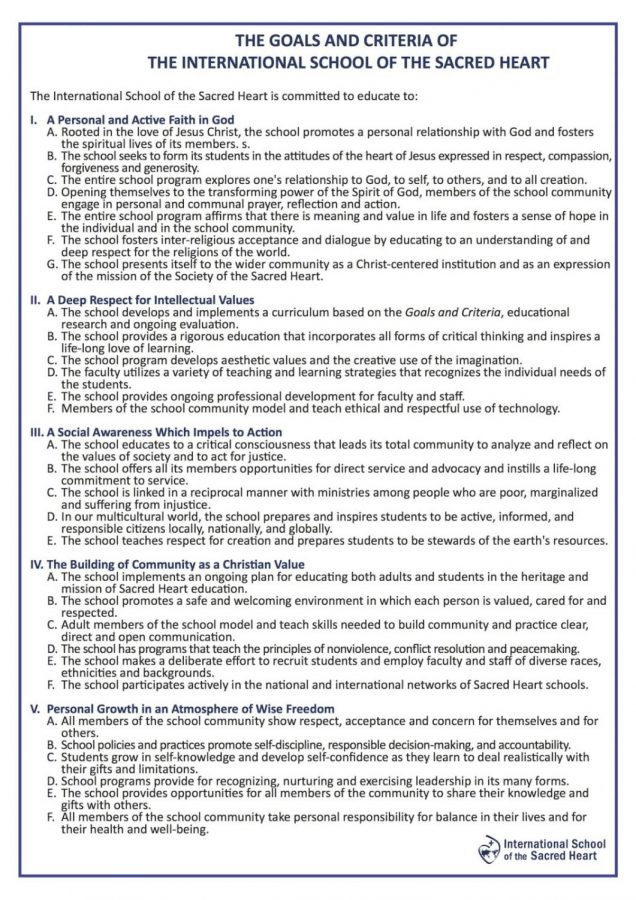

These five goals are the foundation of Sacred Heart education for all Sacred Heart institutions globally. Both teachers and students are consistently reminded of these goals as they are the guiding philosophy.

I often hear people from both in and out of the Sacred Heart community criticize our enclosed circle for being too “nice”, too respectful to each other. Over the seven years I have been at this school, I have come to realize that these criticisms aren’t entirely false. Our perhaps consistently emphasized values-based education almost seems to put the Sacred Heart community before individuals — although, not necessarily when actually studied — and our students do in fact tend to manifest such qualities as humility, especially when compared to students from other schools. However, does this have to be something to fix? As much as the “five goals of Sacred Heart” and the institution’s values sound almost regressive in today’s frenzied search for individual profit and benefit, this identity of Sacred Heart is what I believe separates real “freedom” from selfishness.

As Schur repeatedly stresses in both his show and his interview, we must continue to strive for a better understanding of this social responsibility that each of us has; we will always have to fight the urge to “hack” the system; we will always have to try to make the right decision.